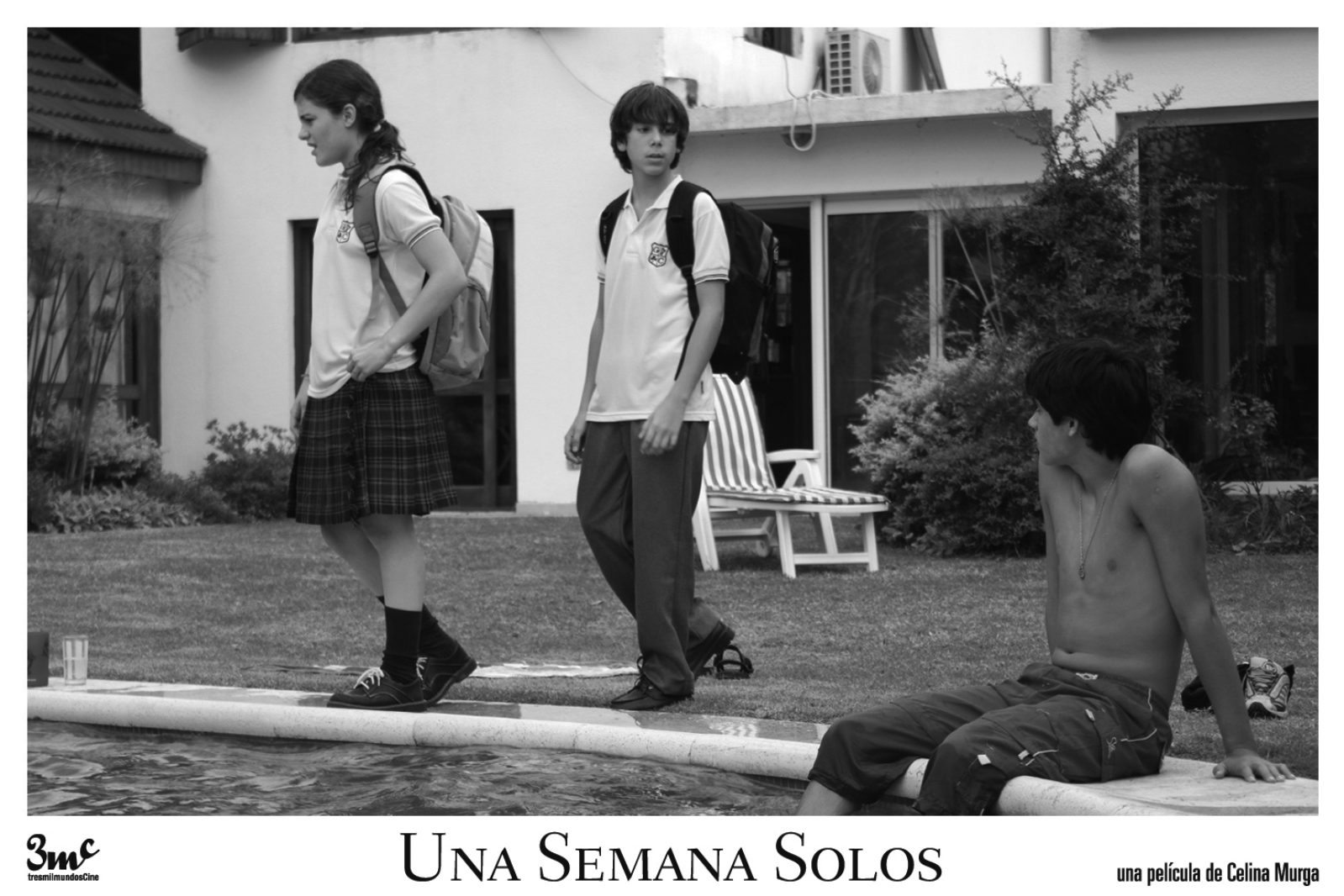

Teenagers and children adrift in the territory delimited by a closed neighborhood, a model scale citadel: houses with gardens, a school, a party hall, a pool. A round trip from leisure to tedium, with no fathers or mothers close, the orphaned-for-a-week kids circulate to create their own chaos regime in the commodity of an accepted prison: no one even tries to run away from there. In that everyday state of conformity a stranger joins them.

From the first film to the second, the inspiration is not so much a frame of mind or the director’s stand on society, but something more secret and fine threa- ded. From Ana y los otros to Una semanas solos, the small-town wandering of a 20 year old girl in search of her former friends and lovers, to the wondering about of a bunch of kids in a residential fortress kept by a local vigilante group, one feels that this young filmmaker deepens her personal positions, stands up for her ideas and makes a claim on her work. Una semana solos is staged and fueled by society trends: these parallel cities, dead cities which proliferate in South America (on the North-American model), gilded prisons where a privi- leged caste tans in the sun next to their swimming pools but remains totally cut off from the world. The children in the film, left to their own devices in this luxurious district deserted by their parents, wander about from one house to another, when suddenly they bump into an outsider: another child, the maid’s son, relocated here by chance for an afternoon. This incongruous presence, this forced transplant, which does not take, is filmed by Celina Murga with constant attention to cinematic precision, describing the motion of life, and its outcomes. It is clear that beyond a specific global motion between social classes, the filmmaker tackles the decline in behavior of children coming from various social backgrounds. To some extent Ana is asked to answer the same question: Can we measure, by going from one place to the other (from the capital to her provincial birthplace town, from the poor districts to the rich districts), people’s attachment to their social status. For Ana y los otros the answer was melancholic. That of Una semana solos is violent, because the children are like privileged people withdrawn in their fortified camps: their capacity to pretend nothing is going on both protects and destroys them. Jean-Philippe Tessé

Participation in the 2006 Buenos Aires Produire au Sud Workshop