Introduction

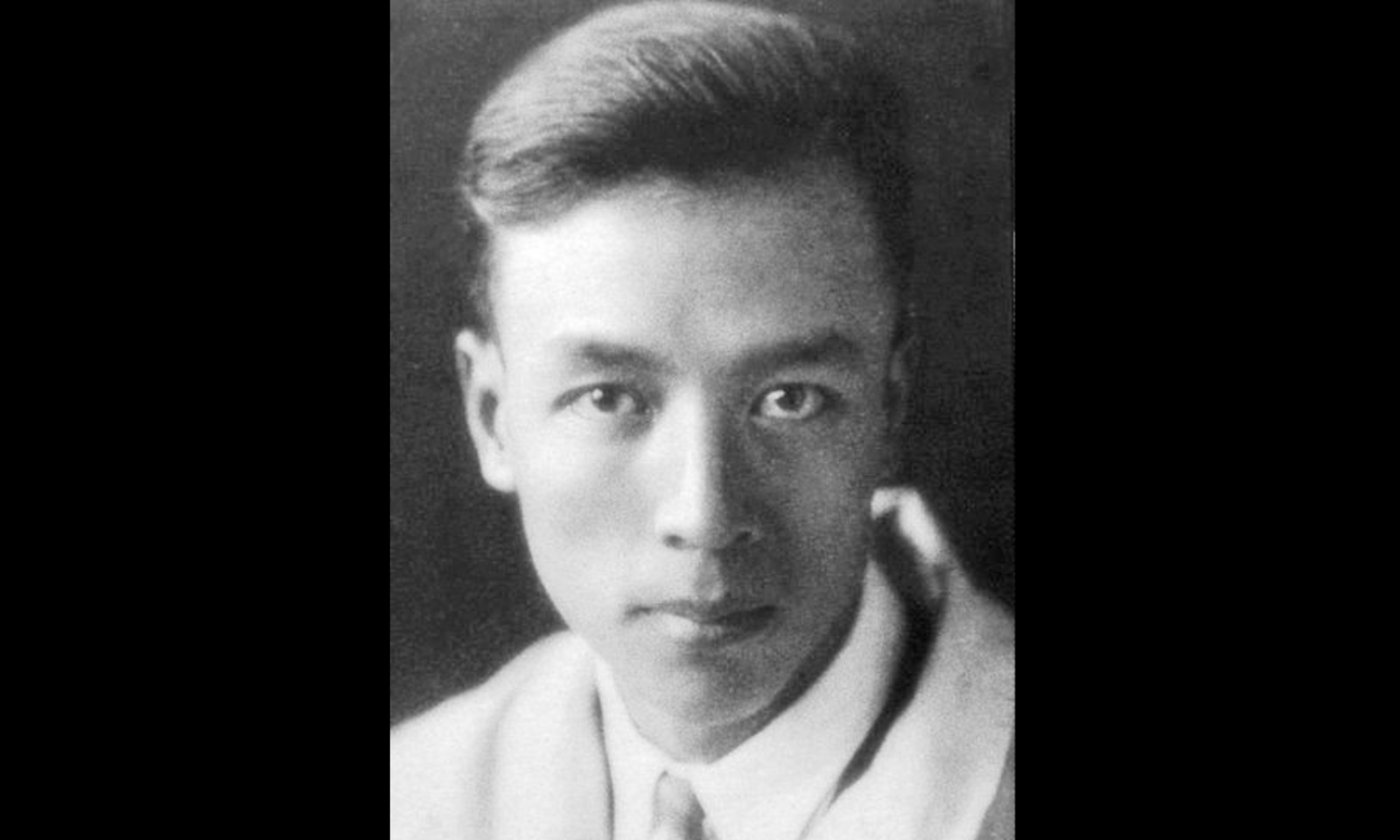

When the director Sun Yu (1900-1990) wrote this text in 1979, Mao Zedong had been dead for three years and China was emerging from its traumatic decade-long Cultural Revolution, during which the filmmaking community had paid a heavy price. Sun Yu himself is a tragic example of the way in which the Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, crushed some highly talented artists in the name of the revolutionary ideology. The director, who had begun his career in the 1920s, after studying in the United States and making some of the 1930s’ finest films, had the misfortune to make a film in 1949, The Life of Wu Xun, which thoroughly displeased the new regime. A critique, doubtless penned by Mao Zedong himself, triggered a very violent campaign against the director and the filmmaking world, bringing them to heel. And Sun Yu’s career was halted in its tracks. After 1950, he only made three other films and suffered relentless attacks from a regime that was never to rehabilitate him. This throws light on the tone of this article, in which Sun Yu aspires to rewrite the history of pre-1949 cinema in line with the norms and vocabulary then used in Communist China, trying to justify himself by a self-critique that reveals the despair of a banned artist with a very limited freedom of opinion. His critique of Lin Biao and the Gang of Four, who had been active during the Cultural Revolution, obeys the political directives of the moment. The main purpose of the text was to separate the “good” progressive films from those productions unacceptable to the Maoist regime for reason of their content and often very Hollywoodian style. His article also aims to assign a major role in this history to the CCP, although in fact it had virtually none albeit for the actions of a few isolated individuals. This history still prevails in China today as, for example, in the 1930s films conservation policy based on a list of so-called “leftist” films, including some cited here by Sun Yu. Yet, it suffices to see these film to realise that they are much more than standard revolutionary productions. Like the May 4th Movement, which owed nothing to Marxist ideology but a great deal to the spirit of the Enlightenment, these are original artistic creations with multiple influences, committed to their times certainly, but very far-removed from the propaganda films later imposed by Mao.

Anne Kerlan

Sun Yu

“ It is now sixty years since the inception of the May 4th Movement. It was a revolutionary movement that attacked imperialism and feudalism from a very much stronger position than that of the 1911 Revolution, and it heralded a new phase in the country’s bourgeois-democratic struggle against those two evils. It ushered in the New Democratic Revolutionary period, and its impact on the course of the Chinese Revolution was incalculable.

The spread of Marxist-Leninist ideology after the October Revolution in Russia had an immediate impact in China, which had suffered thousands of years of feudal rule and more than one hundred years’ imperialist aggression. China’s intellectuals, in particular, saw the new ideology as a ray of light in the pervasive darkness. There was a great awakening : students mounted a huge demonstration on 4 May 1919, at a critical moment in the nation’ s history, when disaster seemed imminent. This demonstration launched a struggle that lasted for over a year. I was attending Nankai Middle School in Tianjin at the time, and I joined with other students in protesting against the capitulationist policies of the Northern Warlord government. The patriotic turmoil of those meetings and demonstrations formed my initiation into the Revolution. If we look back over the development of cinema in China, the period between about 1913 and 1924 can be seen as a pioneering stage. The capitalist producers of this period were speculative businessmen, bureaucrat-compradors and academics of the old school, and the films that they made were mostly light-hearted comedies and murder mysteries. These producers were based in a Shanghai that was caught between feudal and colonial society, and their motives were fundamentally mercenary. In 1924, the Mingxing Film Company made a film called Orphan Rescues Grandfather, whose morality was feudal and ideas were bourgeois reformist. It turned out to be a highly profitable venture, and it led to a period of false prosperity in the nation’ s film industry : in a matter of two years, over 140 film companies were formed, almost all of them commercial in orientation. The so-called directors of the time did not use the kind of shooting-script we do today, much less any more detailed form of pre-planning. Often they had no script at all: some directors walked around with a copy of a novel or folk-tale in their hand, or simply worked from notes they had jotted down on a cigarette pack. Their films had a limited range of content. Many were treacly love stories of the ‘mandarin duck and butterfly’ variety, or ‘classical! costurme tales which resembled neither ass nor horse. The rest were garbled martial arts fantasies, which poisoned the minds of children with feudal superstitions about demons and ghosts.

ln 1927, l returned from studying theatre and cinema in the United States and began working in the film industry. Eight long years had already passed since the birth of the May 4th Movement, but none of its revolutionary spirit had penetrated the film world, controlled as it was by commercial entrepreneurs. l was confused and depressed by the imperialist and feudal attitudes that most of the films propagated.

After the failure of the 1927 Revolution, however, the public’s political awareness significantly increased, and there was a noticeable demand for films that would reflect everyday life and new political aspirations. At the same time, some of the capitalist film companies were searching for new ways ta stave off competition from foreign film imports. It was in these circumstances that the Lianhua Film Company was founded in the early 1930’s. Lianhua hired the services of several intellectuals of the ‘May 4th’ generation, and produced a number of serious and conscientious films that reflected the society of the time. In a tentative way, these films articulated the progressive ideas of the May 4th Movement, and they attracted the attention of intellectuals and a substantial section of the mass film audience. l myself worked for the Lianhua Film Company in this period, as a writer and director. In the following notes, I aim to discuss the general situation in the film world of the early 1930s, with particular reference to developments at Lianhua.

The first film made at Lianhua was Spring Dream in the Old Capital. Written by Zhu Shilin and Luo Mingyu, it was based on the the story of a primary teacher in the suburbs of Beijing, whose quest for fame and fortune led him to neglect his wife and daughter. The story’s tragic conclusion was, at least ta some extent, an indicment of the decadence and dissipation that existed in a society ruled by warlords. I directed the film, and in the course of my work made a major effort ta strengthen the theme and improve the plot, as well as attempting to raise the artistic and technical standards. I went on to write and direct Lianhua’s second production, A Flower Among Weeds, which was released in the autumn of that year. This was a sad, painful love story about a kind-hearted flower-girl who becomes a star in the opera world of Shanghai, but then suffers because of her class background. A glance at the audiences attracted by these films revealed that intellectuals who had long since stopped going to Chinese films because of their shoddiness were returning to the cinema.

The fact that both Spring Dream in the Old Capital and A Flower Among Weeds were box-office successes gave the various film company managements some food for thought. It was as if they realised that their opportunistic production policies would, in the long run, prove suicidal – and that the Chinese film industry might have a great future if they approached the choice of subjects and the artistic aspects in a more serious way, respecting the audience’s reasonable expectations.

The Lianhua company expanded the scope of its operations in 1931, and its ranks swelled to include a number of other creative personnel who were set upon raising standards. These included : Shi Dongshan, who had been with the Dazhonghua Baihe Film Company, and who brought refined techniques and a keen aesthetic sense; Yang Xiaozhong, who already had a wealth of experience ; and Cai Chusheng, who left the comparatively moribund Mingxing Film Company after working for several years as ‘executive director’ for the old director Zheng Zhengqiu. These rather youthful and progressive film workers came together in a creative friendship founded on mutual help and inspiration.

l wrote two film scripts during 1931. The first, entitled The Soul of Freedom, was a historica1 subject : the 72 martyrs of Huanghuagang, who resisted the imperial rule of the Manchus. This focussed on a young martial artist from the lowest rung of Cantonese society, who dies heroically in the strugg1e for freedom. (The film was directed by Wang Cilong, because l fell ill at the time.) The second, entitled A Wild Rose, was written after the Mukden Incident (the first Japanese offensive in Manchuria, 18 September 1931). This centred on the brave daughter of a fishing family, and highlighted her spare-time training in martial skills with a group of poor children, to prepare themselves to meet the risk of an imperialist invasion. I directed it myself, towards the end of the year, and completed it amid the sounds of battle on 28 January 1932. Lianhua also broke new ground in his choice of performers. Ruan Lingyu ‘s performances in Spring Dream in the Old Capital and A Flower Among Weeds stretched her already remarkable abilities. The youthful vigour and sincerity of Jin Yan and Zheng Junli made the slick and superficial ‘heroes’ of earlier films pathetic by comparison. And Wang Renmei’s forceful, positive persona paled the insipid beauties who had hitherto reigned in films into insignificance…

In the two brief years of 1930 and 1931, then, sare of us who had had our intellectual formation in the May 4th Movement made a number of films that were in varying degrees progressive. Our achievements could partly be attributed to our scientific and democratic leanings, our hostility towards superstition and old-fashioned ideologies, and our general support for progressive ideology. But they were also due to the help and influence of certain radical individuals and Communists – in particular, Comrad Tian Han.

The year 1932 saw a ‘left turn’ in the Chinese cinema. A new spirit of revolution was born in the surge of anti-Japanese feeling that gripped the country and in the progress towards a lively left-wing cultural movement. The Communist party responded to these circumstances by deciding to provide direct leadership within the film industry : Comrade Xia Yan was appointed to head a film group, and the group’s activities steered the movement into a historic new phase. Beyond this, the majority of film workers had been deeply affected by the open warfare of the September 18 and January 28 Incidents. With the encouragement of the party’s progressive film reviews, another great awakening occurred. Seven or eight film companies (Lianhua, Mingxing, Yihua and Tianyi amongst them) began to make features and documentaries on the theme of resisting Japanese aggression. Soom afterwards, such party members as Xia Yan, Yang Hansheng, Situ Huimin, Yuan Muzhi and Chen Boer began to move from advisory positions to actual participation in production. The party’s film group took over leadership of the creative committee at Mingxing in 1932. Xia Yan (under such pseudonyms as Ding Qianping and Huang Zibu) wrote a number of screenplays for Mingxing, including Wild Torrent, 24 Hours of Shanghai and an adaptation of Mao Dun’s story Spring Silkworms ; these completely reinvigorated the company’s productions. Similarly, Yang Hansheng wrote Escape, Sad Song of Life and Angry Tide of China’s Seas (under pseudonyms) for the Yihua Film Company, and Chronicle of Suffering for Mingxing. And Tian Han wrote such scripts as Three Modern Girls and Light of Motherhood for Lianhua. The Diantong Film Company was established and led by the party in 1934. Its first production was Plunder of Peach and Plum (aka Fate of a Graduate), acted by Yuan Muzhi and Chen Boer, and directed by Ying Yunwei ; the company’s subsequent films included such progressive titles as Statue of Liberty, directed by Situ Huimin.

In general, these films all represented a distinct advance over the films made before 1932, from both ideological and artistic points of view. On the ideological front, the guidance of a proletarian outlook made it possible to articulate the spirit of the May 4th Movement with a new breath, accuracy and depth. More and more films were made with working class people as their central characters rather than as shabbily dressed objects of scorn. The welcome accorded to these films by the public led the management of many film companies to announce changes in company policy. The result was that the revolutionary tradition of the May 4th Movement spread wider than ever : the slogans “Popular literature and art” and “Go among the people” were heard increasingly often.

Until Shanghai fell to the Japanese in 1937, the various film companies continued to produce occasional films that net the real needs of the time, thanks to the continuing influence of the party. Such films were Yuan Muzhi’s Street Angel, acted by Zhao Dan, Wei Heling, Zhao Huishen and Zhou Xuan, and Shen Xiling’ s Crossroads, acted by Zhao Dan and Bai Yang, both made for Mingxing. Lianhua’s progressive productions inc1uded Cai Chusheng’s A Lost Lamb and New Women, as well as Song of the Fishermem starring Wang Renmei, which won a prize at a Soviet film festival. Two films that I wrote and directed at this time were The Little One, with Ruan Lingyu and Li Lili, about a group of handicraft workers and their growing patriotism, and Big Road, about the struggles of road builders. The latter had a score by the popular young musician Nie Er : he wrote the overture, titled The Pathbreakers, with lyrics by Sun Shiyi, and the theme song Big Road, for which l wrote the lyrics myself.

These songs, full of stirring l’evolutionary optimism, heralded the coming political struggles and launched the tide of proletarian music in China. Two other films made before the Japanese occupation were Wu Yonggang’s Courage that Reaches Above the Clouds and Xu Xingzhi’s Children of Troubled Times. The latter featured Nie Er’s last, immortal masterpiece The March of the Volunteers, which was ta become the national anthem for OUT great People’s Republic of China.

I hope that I have said enough to show that the film industry of the 1930s, under the guidance of the Communist party, managed to uphold and further the revolutionary spirit and ideology of the May 4th Movement. It met the needs of the time in encouraging resistance against the Japanese invaders and the reactionary rule of the KMT. In no sense was it the origin of an ‘evil trend’ in Chinese cinema, as Lin Biao and the ‘Gang of Four’ alleged. The truth is that the achievements of the time would have been inconceivable without the leadership of the party.

Needless to add, the conditions prevailing at the time meant that the various Shanghai film companies, including Lianhua, made a number of films that were negative and unhealthy, based on essentially feudal values and showing ideological confusion. Such films, however, had little social impact. Furthermore, those of us who had progressive leanings, whom the party rallied around its leadership, remained in varying degrees influenced by our old ideologies and our bourgeois outlook on art. It was inevitable that we would make mistakes in our films. There was still a considerable distance between us and the working people; in portraying them, and expressing our sympathy and admiration for them we could not possibly represent their temperament, their language and their actions with complete accuracy. Of the twelve films that I directed in the 1930s, apart from two that dealt with intellectual themes, all took the urban poor or the peasants or the workers as their protagonists. (One of them was about army life.) Although l tried my utmost to do justice to the spirit of resistance and revolution shown by these heroes, my observation and characterisation of working people remained largely superficial : I neither did nor could immerse myself in their lives. Some did better than I. Nie Er, for one, succeeded in establishing comradly relations with building workers while he was composing such songs as the theme for Big Road. As a result, he gained much deeper insight into their lives than most of us. His identification with working people in their lives and struggles enabled him to create a musical image of them that was true to life, and to reflect their great revolutionary optimism. Nie Er was certainly one of the intellectuals who most actively implemented the May 4th slogan “Go among the people”.

The revolutionary spirit of the May 4th Movement was upheld and furthered in the cinema of the 1930s, under the party’s leadership. Now, sixty years on, those of us in the field of literature and art should treasure the movement’s great heritage. As part of the working masses, we should make full use of our literary and artistic weapons to oppose aggression from imperialists and social imperialists, to develop socialist democracy, to promote science, and to contribute towards the speedy realisation of the socialist Four Modernisations.”

Translated by Paul Crook.

First published in the magazine Dianying Yishu (Film Art), No. 3, 1979.