Wong Ain-ling

Everything has to go back to the fall of Shanghai.

The unoccupied foreign concessions of Shanghai became known as the ‘Orphan Island’ between the end of November 1937 when the city fell and 8 December 1941 when the Pacific War erupted. During this murky time in history, the political landscape took on a new complexion in the already ragged terrains of the concessions. But the film industry surprisingly revived itself from the initial setback and boasted a flourishing façade. Those who have seen Truffaut’s Le dernier métro (1980) will understand that people living under oppression are in desperate need of a refuge, a measure of peace to their weary bodies and souls; a French leave, you might say. Capitalising on this extraordinary opportunity, the business-savvy and astute Zhang Shankun produced Hua Mo-lan (Mulan Congjun, 1939, directed by Bu Wancang [aka Richard Poh]), a film that entertained, hit the patriotic nerve and jump-started the craze for costume drama.

Fei Mu began shooting Confucius in early 1940 on an initial budget of $30,000, planning to wrap up filming in March. By August, the budget spiralled to $80,000 while the camera was kept rolling. According to the film’s producer Jin Xinmin, the final bill came in at $160,000 and the film took the director Fei Mu an entire year to complete. But allow me to speculate: although known to invest time in quality, Fei Mu must have has encountered more than his share of obstacles not just of a technical nature during the production of the film. The end of the 1940s saw world politics taking a turn for the worse, the situation even bleaker in China, making it virtually impossible for filmmaking. Fei Mu could very well be locked in a paralysing impasse, similar to another unfinished project after the war The Magnificent Country (1946): The Magnificent Country is allegedly based upon the third united front formed between the Nationalists and Communists to negotiate a coalition government and rebuild the country after victory. However, with the Civil War erupted in 1946 shortly after filming began, the script underwent repeated revisions in light of the ever-changing political upheaval, a wearisome task that consumed Fei Mu three years and led to nothing. If my supposition is correct, there may be a larger context in which the seemingly incongruous ending of Confucius makes sense – Fei Mu was seeking to reconcile his frustrations with the need to seek self-assurance to fight a lonely battle.

Confucius made its overdue premiere at the Jincheng Theatre on 19 December 1940 and was running up until New Year’s Eve; after an eleven-day hiatus, the screening resumed at the newly inaugurated Jindu Theatre but the curtain was drawn after merely a week. At the same time, the costume drama craze ran its course with the passing years, first giving way to a short-lived frenzy of folklore films before finally steering towards contemporary drama. The city of Shanghai fell completely to Japanese occupation in the end of 1941 and its film industry lorded over by the enemy, prompting Fei Mu to transfer his creative endeavours from the screen to the stage.

I

Leafing through the Shen Daily around the time of Confucius’s release, two things leap out. First of all, while Min Hwa Motion Picture financing the production of the film may be a rookie to the business, it proved to be an old hand at marketing and publicity. The marketing campaign the studio had put together comprised a special brochure – ‘A fully illustrated octavo complete with full-colour cover”, ads placed in the film section of newspapers, a Confucius Essay Competition, and discount matinee tickets for groups. The extraordinarily high level of expectation and support pledged by people from the cultural sector in form of essays and criticisms was reported back-to-back in the Shen Daily during the entire film’s run. What’s more, some articles were compiled into a special issue, suggesting an exclusive VIP treatment reserved only for Confucius. Although the film boasted neither an A-list female cast nor a heart-stirring plot, the artistic perseverance of director Fei Mu and the fierce sense of obligation held by producers Jin Xinmin and Tong Zhenmin (aka Tong Lian) struck an emotive chord with literati who got the tide right for the film’s launch.

In the screenwriter Fei Mu’s hands, the script serves to highlight Confucius’s noble character and thinking while striving to give the character a ‘human quality’. Living in a turbulent time, the master fell victim to a web of political intrigues and deceits and experienced sufferings and hardship first hand. The master and his disciples were stranded in the bordering area between the states of Chen and Tsai (Cai) where the caravan ran out of food; he also suffered the anguish of losing both his son and his favourite disciples at an advanced age. Despite these adversities, he remained undaunted in his mission to expound his political beliefs and emerged with his integrity intact. Confucius is truly, in the words of Fei Mu, ‘[a] great educator, thinker and philosopher doomed to be a victim of the politics of his time.’ In other words, he is a failure in real life. Confucian teachings, having been made the state ideology through suppressing the ‘Hundred Schools of Thought’, had been conveniently used as an ideological tool for rulers throughout the ages. Nationalist leaders too saw the value of Confucian ideals and virtues and blended them with Nationalistic sentiments. Filmmaker Fei Mu could not be oblivious to all that but he still looked to the great saga for inspiration. On the other hand, an ideological rhetoric engendered by the sentiments of the May Fourth Movement predisposed some people to hope that Fei Mu would ‘use his film as a pointed and satirical commentary to critique the fundamentals of Confucian teachings, highlight the disparity between the time of Confucius and ours, and show that Confucianism is no longer valid in China nowadays.’

Fei stood his ground and was unflinching under the weight of this invisible pressure, the response of a man who had things well thought out. By referencing Carl Crow’s Master Kung, he disavowed himself of the role of a god-maker: ‘Confucius the saint and Confucius the man are two characters. “Confucius” is flesh and blood, a kind and sincere scholar and gentleman; he…experienced the pain of shattered dreams and hopelessness never experienced by mankind before. On his deathbed, he himself called his life a failure. “Confucius the saint” is the creation of later scholars of a god-like persona whose every move and word is exalted as sacred, turning him into a “mysterious icon of knowledge” devoid of flesh and blood.’ On the other hand, the director admitted to adopting ‘a more or less “sublimation” approach’ to filming Confucius with the intention of inspiring contemplation of pragmatic issues. Coincidentally, no sooner than Fei had quoted in ‘Confucius: His Life and Times’ from Hu Shi’s classic, Outline of the History of Chinese Philosophy (Zhongguo Zhexue Shi Dagang), Hu’s article ‘How China Fought a Long War’ appeared in the Shen Daily on 5 January 1941. Discussing the historical consciousness of the Chinese nation, Hu traced its origin back to her ‘living under one empire, one administration, one law, one literature, one education system and one historical culture from since 2,100 years ago.’ The ancient and long ‘historical culture’ Hu referred to complements the sentiments of Fei’s portrayal of Confucius whose spirit refuses to succumb.

II

But film is art after all, and that if this heavy and obscure biopic somehow manages to tug at our heartstrings more than half a century after it first hit the screen, it is largely due to the strength of its film language that relates to the tragedies and sorrows of a time and resonates throughout the ages to the present. Where not up to scratch in recording, set design, performance of the side cast and the texture of the costumes by today’s standard, Fei made up for them by bringing maturity to artistic conception and expression, and there appears to be considerable evidence that he was far ahead of his contemporaries.

In 1933, Fei made his directorial debut, Nights of the City, and this was immediately followed by Life (1934), Sea of the Fragrant Snow (1934), all starring the crowd-puller of the day, Ruan Lingyu. Despite the handful of archival materials extant on Fei’s early films, the few short essays he penned in 1934, including ‘From the Director of Life’, ‘A Small Question in Sea of the Fragrant Snow : The Use of Flashbacks and Conjecture’ and ‘On “Air”’,5 all indicate his concern with two issues: the conditions of human existence and the artistic expression in film, the two being inseparable.

From the beginning, Fei chose to break off from the mainstream, conscientiously trying ‘to avoid the formation of dramatic points and follow a none-dramatic path.’ The surviving print of Song of China (1935), albeit an incomplete one with a running time of 47 minutes, reveals a rhetorician who well articulated his early vision in film. While Hollywood and even Soviet Union influences were noticeable in the works of his contemporaries, Fei Mu’s films offer a serene and idyllic charm with a distinctly European flavour, eschewing the build-up of dramatic tension through a series of climaxes.

In 1936, a re-edited version of Song of China was screened at the Little Carnegie Playhouse in Midtown New York. In a tantalising New York Times film review, the critic observed:

‘But the performances [of the actors], unlike those of the Chinese theatre, are thoroughly Occidental, are even more understated, in fact. In a sense this was disappointing, for, being prepared for a Chinese picture, we expected the sweeping gestures, the exaggerated pantomime of the traditional Chinese drama.’

Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain (1936), made a year later, is strikingly modern and ahead of its time. Made in the time of national tragedy, it has a plot so simple that Fei himself described as ‘a story that can be told in two lines.’ The story of villagers fending off the wolf is used allegorically to evoke solidarity among the Chinese people in the fight against the Japanese aggressors. The series of ensemble scenes are interpolated into a largely conceptual narrative through the interplay of character and characterisation as easily recognisable and as archetypal as the jing (the “painted faces” ) and dan (female role) of Chinese opera. Despite the many production constraints, Fei Mu was able to translate abstract ideas into real sentiments by using a tremendous range of location shots, extraordinary compositions and montage, and somehow whips up a contemporary fable out of thin air. The director’s quest for a pure film language and to get rid of ‘the poison of wenmingxi (civilised drama)’ during his early filmmaking days all culminated with Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain.

In similar fable-telling fashion, Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937) peers into the realm of dream as the camera returns from the vast openness of the nature to a claustrophobic enclosure, and the cast traded a subdued performance in their earlier works for highly exaggerated gestures and facial expressions characteristic of the stage. In this succinct work, Fei again responded candidly to the time periods in which the film unfolds. What’s surprisingly is the way he used a sensual boudoir imagery – ‘She makes love like gentle rain… She slumbers under clouds of Witch’s Mountain’ – in Peony Pavilion to allude to the nightmarish reality of the Japanese invasion. Although shot entirely in silence, with stark light contrast and exaggerated character designs that suggest strongly of a German expressionist influence, the blood of traditional Chinese literary is still running in its veins. Then in the adaptation of the opera great Zhou Xinfang’s masterpiece, Murder in the Oratory (1937), the stage and the screen collided, marking a return to the minimalist aesthetics of traditional opera as the filmmaker took an important step of contemplating and exploring film art. While its subject matter may not strike a chord with the contemporary audience, the intricate ties and conflicts between morality and humanity, individuals and fate portrayed in the film are compelling representations of Greek tragedy; the profound sense of loss and grief speaks volumes about the suppressive and depressive way of life that was a constant in the War of Resistance.

Aside from the often heard and seen masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (1948), the only surviving film from the period 1938–1948 in which Fei Mu played a part is Children of the World (1941). Directed by an Austrian couple, Louise and Julius Jacob Fleck, who were stranded in Shanghai during World War II, Fei was credited with writing the screenplay but was likely to have contributed only an archetype of the story. The recovery of Confucius, a film long thought lost, provided the vital link to the decade-long void.

III

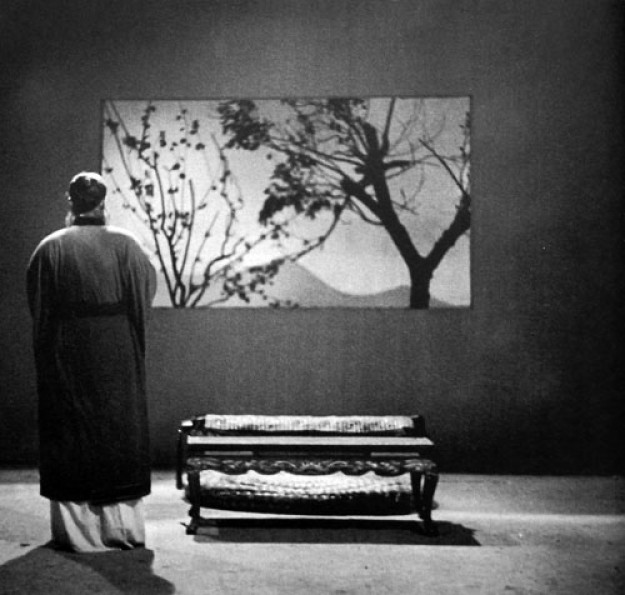

Viewing the film for the first time at the Hong Kong Film Archive end of 2008, two films came to my mind: Carl Theodor Dreyer’s La passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and Éric Rohmer’s Perceval le gallois (1979). The cultural and historical background that inspired the films was as different as chalk and cheese, showing that art often works its magic in a most mysterious way. In Dreyer’s work, the unadorned face of the title damsel fills the entire 1.33:1 frame, confronting the viewer with an extraordinary power that strikes the soul. Fei Mu, however, paints his canvas of 1.16:1 Movietone with austere mise-en-scene and graceful composition, portraying Confucius’s perseverance and sorrowful dignity against worldly dictates. Aesthetic orientations put Fei and Dreyer on either side of the West–East divide. Yet both bring the sentiments of an ascetic to the fore in a non-dualistic combination of the abstract and the figurative, and both were concerned and seeking to offer a solution to an artistic problem: the representation of a historical figure’s spirituality in film.

Compared with Dreyer’s La passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the legend of the medieval chevalier depicted by Rohmer is an entirely different interpretation. Eschewing the realist tradition of Western cinema, Rohmer instead draws his inspiration from the visual sensitivities of mural and glass paintings as well as music and poetry of the Middle Ages. The result was a different take on ‘realism’ in which flesh-and-blood horses roaming among fake trees along a stream of episodic narrative. Fei Mu was evidently engaging in the same aesthetic pursuit in the 1930s and 40s, attempting by way of deduction – ‘complement shapes with light’ and ‘do away with dispensable things’ – to create the ‘air’ and to present stylised emotion and expression pertaining to the conventions of the traditional stage. These experiments reached fruition in Confucius. Rohmer, Fei and other artists of their time all attempted to trace the cultural origins for the behaviour and values of the contemporary man. After making Six contes moraux (1962–72), his first film cycle, Rohmer directed La Marquise d’O (1976) and Perceval le gallois. Why would he take on the challenge of making two period films? These factors may offer plausible explanations, particularly for the latter film: the knight spirit in Middle Ages is long considered as a social exemplar in the West; as for Fei Mu, he too imbued his films with the enduring Confucian ideal of ethical integrity in human relations. With the country verging on the brink of collapse, he delved deep into the roots of Chinese culture in search of a way out. He might have failed to think things through thoroughly, but he was doing what an artist, as opposed to a philosopher, did best and produced a film of refreshing integrity that really tugs at the heartstrings. This year, the Archive will be presenting a further-restored version of Confucius, which has incorporated about nine minutes of loose fragments shown separately at its initial phase of restoration. Bearing the scars of the time, this newly restored archival classic helps us to better appreciate the vicissitudes of history.

(Reprinted from Wong Ain-Ling (ed.), Fei Mu’s Confucius, Hong Kong Film Archive, 2010.)

Translated by Agnes Lam