There is currently a deep change in the structure of Argentinian cinema which has traditionally been of a mainly commercial and industrial nature. Over the last two years, a major cultural transformation has made it possible for a new generation of film-makers, who tell the problems of the youth with realism, to come to the fore.

One can also note a metaphorical effort expressing with a sort of boisterous irony what is, after all, the tragedy of unemployment, the destruction and instability of governments due to the gigantic external debt, as well as the future of young adults. The increasing number of film schools largely contributes to providing this intimist cinema with a solid technical basis.

In early 1998, Pizza, birra, faso, made by Adrian Caetano and Bruno Stagnaro, both in their twenties, was discovered by filmgoers. It was a promising film that suggested other similar films would follow.

Pizza, birra, faso marks the beginning of an odd review of characters who reflected domestic migration. With Mala época (1998), a collective film made by the Universidad del Cine, the review turned into an inventory of individuals from Argentina’s neighbouring countries — Paraguayan, Bolivian and Peruvian migrants never portrayed until then in Argentinian cinema. Both films avoid the picturesque and give a realistic rendition of the characters’ private lives.

Mundo Grua (1999) was made in the same spirit, in black-and-white 16mm, then blown up onto 35mm. Pablo Trapero, its director, then a student at the Universidad del Cine, shot it during weekends in Buenos Aires and a popular district in Patagonia. This light comedy describes the harsh daily life of a crane operator who loses his job several times — a dreadful situation in a country so severely hit by unemployment.

Its description of a man’s, and society’s, hardships made Mundo Grúa a reference for the young generation of film-makers.

Like Mundo Grúa, Martin Rejtman’s Silvia Prieto (1999) is another film made up of minimal stories. Silvia Prieto is a woman who hates other women who share her name and who is scared that her own personality might melt into each of these other women to such an extent that she might not be any of them. Faced with such a strange affliction, she finds comfort in coming to terms with who she is.

Silvia Prieto is Martin Rejtman’s second feature. His first one was Rapado (1996) which was not very successful. In this film, the film-maker drew and ironic, obsessing and perverse sketch of the world as we know it, stretching it to feverish, zany and joyful limits.

Despite this new batch of film-makers, there are fears that, once the passing fancy has subsided and due to the lack of funds and infrastructure, they will not be able to make a second film.

One gets the impression that these films express disillusion, yet do not offer any constructive criticism of the reality they describe so painstakingly. They do not attempt to amend reality, they only show it as it is within a personal story. Their aim is not to make masterpieces; they get their inspiration from daily life and the simplicity of a familiar environment. They stand out for their great sensitivity and a definite ethical outlook.

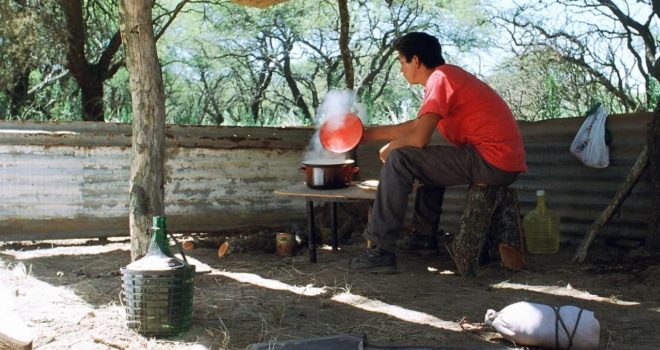

This year three films gained some sort of recognition in international festivals: Lisandro Alonso’s La Libertad (2001, first film), Adrian Caetano’s Bolivia (1999-2001) and Lucrecia Martel’s La Ciénaga (2000-2001, first film).

La Libertad is a stylistic composition in pure cinema resting mainly on the image, with a practically non-existent story (a lumberjack chops down a tree, sells the wood and swallows a rodent). A very intense film, La Libertad gets the viewer involved regardless of the story. A tension grows between the film-maker’s minimalist vision and a yearning for action.

La Ciénaga promises the onset of a great career for beginner Lucrecia Martel. It tells the story of two declining families of northern Argentina, oppressed by the social context and the heat. The most interesting aspect of the film is its use of the language of images. It has a very dense filmic style which cornes between the unfolding story and the viewer who is disturbed by the impression left by the visual texture and the thin plot. La Ciénaga is a remarkable film.

Young directors do not feel all-powerful. They are aware they belong to a small corner of the globe and do not attempt to change it, unlike the 1960s Argentinian avant-garde film-makers driven by the desire to set up a new world.

The new generation looks at the dark depths of reality and do not bother with the surface of things. Its aesthetics is two-fold as it deals with the textually signified from a minimalist, non-conformist point of view.

The new directors’ language is dominated by the illegible: nothing they say is meant to preserve or change habits. Relationships between the characters and the action are more important than the plot which loses itself in its own narration. Minimalist dialogue makes way for visual language and narrative construction as well as editing — the ultimate film-writing.

This new movement has been labelled “the independents” in relation to an international protest attitude against the big film industry. Through their efforts, they daim to be followers of Jean-Luc Godard, John Cassavettes or Paul Morrissey. They have the economic and moral support of the Sundance and Rotterdam film festivals. Today they have their own independent festival in Buenos Aires where they can show their films.

Currently, the general public prefers commercial productions such as Marcelo Piñeiro’s Plata quemada (2000). Piñeiro would love to bean”auteur”— he is only good at making commercial films which are safer in terms of box office.

In the same vein we can mention two great successes, beginner Fabian Bielinski’s Nueve reinas (2000) and Juan José Campanella’s El hijo de la novia (2001). With a questionable artistic sense, these directors benefit from the financial support of télévision to make commercially-oriented – and hopefully profitable – films. About a million viewers saw each of these films.

The big theatrical networks are yet to show an interest in young film-makers while films do get made by authors in their own right. But they lack a more supportive distribution system for their new way of making films in Argentina.

This year, Pablo Trapero and Adrian Caetano both presented their second films at Cannes, El Bonaerense (2002) and Un oso rojo (2002) respectively.

Claudio España, film critic and teacher at the University of Buenos Aires, Artistic Director, Mar del Plata International Film Festival