CHINESE CINEMA: A UNIQUE NATIONAL HISTORY

When Chinese film-makers first made films at the beginning of the 20th century, they may have already realized that they had finally found a new form of mass media which would become an efficient vehicle for their ideas on modernity. Within twenty years, in Shanghai, then the largest city in the Far East, a major national film production centre was set up with very diversified investments.The exhibition of a large number of films produced at the time, with varied themes -cloak and dagger films, adaptations of classic literature, documentaries, fiction films about daily family life with a high educational and moral stance- which the general audience enjoyed very much, quickly turned the burgeoning Chinese film industry into a major element of urban culture. Until the 1930s, a number of authors emerged and left a mark on the production with very personal styles. The films they made, often remarkable in terms of artistic quality, led the critics to refer to them as a “Chinese school” at the international level. Influenced by political, economic, social and cultural circumstances, as well as by the different schools of thought of the time, Chinese cinema offered a great diversity of films often classified as left-wing films, national defence films, educational films and love stories. In particular, the role of ideology in the Chinese cinema of the time should not be overlooked.

Chinese cinema entered a new phase in 1937 with the war against Japan. Artists exiled and united in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Chongqin and Yan An turned these four cities into new film production centres. The government of the time also created relatively important public companies to promote artistic creation. A new wave, marked by the Chongqin (the provisional Chinese capital) and Yan An documentary school and by war-related production in the regions which were not occupied by the Japanese army, completely changed the Chinese cinema scene: the unique pre-war Shanghai model was being put into question. Yet, in Shanghai itself, which had become a metropolis under Japanese occupation, commercial film production was still thriving, strangely enough, with a great deal of musical films, adaptations of classic literature and love stories. This trend had a great and lasting influence on later Chinese films made on the mainland, in Taiwan and in Hong Kong.

The end of the war was followed by a major period of Hollywood-type, yet definitely Chinese films. Films such as The Spring River Flows East, often three- to four-hour long and produced in extremely harsh conditions, could already compete with American entertaining productions and kept breaking attendance records one after the other. At the same time, an aesthetic and film-language revolution was silently under way, as can be seen in films such as Fei Mu’s psychological films. With his masterpiece Spring in a Small Town, Fei Mu created a modern, yet wholly Chinese paradigm which allowed film-makers to free themselves from formal issues. In this film, the director brilliantly illustrates the harmony between form and meaning, the archetype and narration, very slow camera movements and the art of editing, with the disappearance of structural conflicts. The formal beauty and the film language were expressed in a very natural way and revealed only through the whole narrative structure of the film. The director perfectly knew how to build his own narrative discourse, with a total control of the context and tone which in turn determined the camera movements. This was the major différence between Fei Mu and his Western colleagues when they tried to revolutionize film language in the Fifties with Italian neorealism and the French New Wave, especially as Fei Mu’s films were always marked by a certain oriental wisdom.

Chinese cinema took a new direction after 1949. Within a defined ideological framework, film production was integrated in a planned economy, in cooperation with companies which had ail been nationalised. Its films represented only grand images of the working class, poor peasants and soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army. Faced with such dominant ideological discourse, a number of gifted and devoted Chinese artists tried, not without ingenuity, to successfully mix their own language with their favourite themes, along the ideological line of the time, and gave Chinese cinema works of an exceptional quality. Meanwhile, the artists who made films linked with the Beijing Opera or regional operas, as well as animation films in the Chinese painting tradition, did their own contribution to give China new genres in which masterpieces designed a particularly picturesque landscape in the history of world cinema.

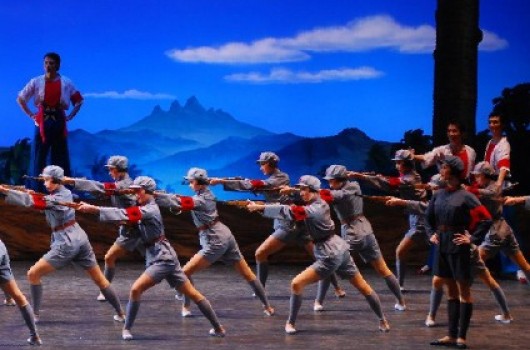

The Cultural Revolution madness devastated the cinema of new China over ten years, Studios then produced films called “revolutionary Beijing Opera films” which some still talk about with nostalgia today. Nowadays most viewers laugh at them; however, their specific film language did bring about some sort of a transformation, with, in traditional arts such as cinema, the Beijing Opera, music and dance.

1978 was at last the beginning of an era of reform and opening. The young generation, sent to the countryside to be re-educated by the peasants during the Cultural Revolution, became the most dynamic and creative section of Chinese Society, through a new awareness and critical attitude. Their spokespersons in the film world were undoubtedly the so-called Fifth-Generation directors. Taking over from their teachers (the Fourth-Generation artists), these young graduates from the Beijing Film Academy together started the new Chinese cinema movement which lasted several years. Yet, behind their new and very avant-garde film language which often took the audience aback, there were the same ideological themes which referred to the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment, developed with metaphors based on traditional stories. With Red Sorghum in 1987, Zhang Yimou introduced epic elements in a Fifth-Generation wrapping. In the Nineties, together with Chen Kaige and other film-makers, he gave the first answers to the questions dealing with the industrialisation of cinema and globalisation. Through a return to the great traditional narrative, the large number of films they made foretold the shape of the film and television industry of the 21 st century.

Chen Shan

Film history teacher at the Beijing Film Academy