TUNISIAN CINEMA: FROM WINNING TO QUESTIONING…

Tunisian cinema was born on a particularly fertile ground, nurtured by a love of cinema and admiration for the great works of world cinema. As early as1922, Samama Chikly, a forerunner of Tunisian cinema and a dabbler who shot the first submarine and aerial (from a hot-air balloon) pictures, made a short fiction film (Zohra) and the medium length Aïn el Ghazel in 1924, starring his own daughter Haydé, and so became one of the early “indigenous” film-makers of the African continent (the first feature film to which contributed an Egyptian director was only made in 1927). Later, in 1949, seven years before it acquired its political independence, Tunisia was already one of the countries in the African continent with the biggest number of film societies.Tahar Cheriaa, the president of the federation of film societies and later in charge of the cinema department at the Ministry for Culture, was set to become the “father” of the first Tunisian film productions (Omar Khlifi’s L’Aube, the first Tunisian feature film, was made in 1967) and the founder of the very first Pan-African and Pan-Arab film festival, the “Journées cinématographiques de Carthage” (JCC, the Carthage Film Days) which are now as popular as they were in 1966. The film societies and the JCC contributed to training demanding filmmakers and filmgoers. Right from the beginning, it was never a case of mimicking the unique, “old” Arab cinema (commercial Egyptian cinema), a great provider of melodramas and musical films out of which a few auteurs were striving to make themselves known.The majority of film-makers would rather try their hand at successfully making, each in their own style, original “expressive” films (about politics, society, culture, etc.) bearing their maker’s touch and aiming for the international quality standards. Apart from a few exceptions, they did so without taking the easy way out, which would have been rewarding only with the local audience. Unlike its neighbours in Maghreb where, for various reasons and in various periods, “epic” and “populist” films were made, such categories are virtually non-existent in Tunisian cinema where auteur films prevail in an almost individualistic manner. These films are often very different from each other: for example, Nacer Khemir’s aesthetic choices have nothing in common with Nouri Bouzid’s. Inspite of a general”family likeness” and common subject matters it has been said that each Tunisian film-maker represents his or her own “aesthetic school”, as we can see in the films shown in Nantes, which were all landmarks in their own time.

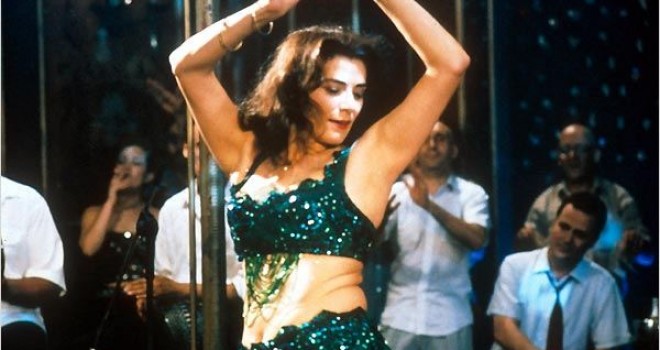

Such freedom of choice was made possible because Tunisia also has a kind of film censorship (different from TV censorship) which is undoubtedly one of the most lenient in the Arab world: scenes that are forbidden in other Arab countries (and edited out from Tunisian films screened there), revealing the celebration of female nudity (Halfaouine), homosexuality (Man of Ashes), political repression (Golden Horseshoes), sex tourism (Bezness), the destitution of poor areas (Essaida), women’s right to sexual enlightenment (Fatma, Red Satin), were eventually approved by Tunisian censorship as long as they were expressed by artists and necessary to the coherence of their work.

All these elements (a wide film-loving audience and great freedom of expression allowing film-makers to deal with bold subject matters confronting what remained taboo elsewhere), as well as the economic rejection of the all-powerful State and the active support of the private sector which enabled energetic producers (such as Ahmed Attia, Hassan Daldoul, Selma Baccar, and today Dora Bouchoucha, Ibrahim Letaief, Nejib Belkadhi, etc.) to emerge, despite difficulties, all these helped create a sort of golden age both for the artists and the audience during the 1986-1996 decade. Of course, during the previous decade, Tunisian cinema had already been a star on the international festival scene with several films such as The Ambassadors (1976), Sun of the Hyenas (1977), Aziza (1980), The Trace (1982), Traversées (1982), and The Surveyors of The Desert (1984), which all received numerous awards in many festivals.

The miracle was that, from Man of Ashes (1986) onwards, Tunisian viewers also acclaimed national films in an unprecedented way, unlike what happened in most Southern countries where auteur films are restrained within the ghetto of art houses or exclusively benefit from the “prestige” of foreign festivals. Tunisian auteur films did much better at the local box-office than the best-selling Hollywood or Egyptian films, even so-called difficult films such as Chich Khan or Soltane el Medina: they created a totally new filmic category — mass auteur films! These films won on the local as well as international scenes through theatrical release in foreign countries, reaching a wider audience than that of the festivals, as was the case for big local successes like The Silences of the Palace, Halfaouine, A Summer in La Goulette, (and later abroad Red Satin). The makers of these films were often honoured by an invitation to be members of officiai juries in major film events such as Cannes, Venice and Berlin. The golden age of the local triumph of Tunisian films stopped after a decade for a number of reasons: the proliferation of very cheap satellite dishes with “pirate cards” (giving free access to subscription- based TV channels) and video shops also offering the latest pirated films have kept the general audience away form the big screen. Also, the fact that ERTT (the national TV network) stopped showing daily promotional trailers of Tunisian films deprived the audience of their main source of information and incentive as far as national films were concerned.

The decline was also visible on the international scene. Unlike Tunisia, Morocco remarkably based the organisation of its audiovisual industry on solidarity (Moroccan cinema is funded by a part of the TV advertising income) and thus increased its annual production (Moroccan films logically replaced Tunisian films in the various Cannes festival sections in a healthy continuity as soon as 2002), Morocco also became a major location for foreign films, whereas Tunisia had been the leader in that respect thanks to Tarek Ben Ammar’s achievement as a famous Tunisian producer of international scale. Today Tunisian cinema is far behind in structural terms.

Tunisia still has no national film centre, no unified ticketing system, no multiplexes (to stop viewers from deserting one-screen cinemas, as this was done elsewhere), no diversified funding sources. It yields no more than three feature films a year, with the help of the praise worthy (and steadily increasing) financial support of the Ministry for Culture and other national and foreign institutional forms of support.

Economic helplessness is coupled with artistic disarray. So far, the success of Tunisian cinema had come from the generation of the 1960s film societies, fostered by a love of the great works of the silver screen, a generation born before the generalisation of television which introduced a new relationship to the moving image.

To stop the decline of the local audience and of the Tunisian presence on the international scene, new film-makers desperately and unconsciously try to mimic what they think were the “recipes” for the success of the previous generation, or the “expectations” of foreign festival programmers. Others explore totally new directions: this is what Raja Amari or Nidhal Chatta did in their first features and what can be seen in a number of short fiction films by newcomers, or in Hichem Ben Ammar’s “ethnographic” and poetic documentaries.

While economic reorganisation is yet to happen, the achievements of tomorrow’s Tunisian cinema will surely come from this new “youngwave”.

Férid Boughedir