It is difficult to embrace in only one stroke the full history of South American cinema and its diverging temporalities, its rising and falling which, since the beginning of the 20th century, made it a cinematographically ongoing continent. Sometimes out-of-the-way news reached us that in such and such a country, at such and such a period; there was something new going on, effervescence that was sometimes coming from schools, or a certain génération, or even specific events. These last years, the vitality of the South American cinema has been very much celebrated, for both the Argentinean fiction, and the Brazilian documentary. It could soon be the turn of Chile, Paraguay or Ecuador. This country that is divided between its geographical identities (the tropical coast, the Andes cordillera, the Amazonian forest) does not count on a solid cinematographic heritage; it lacks the presence of a reference author, a Master, an important national filmmaker. There is this film, They Met in Guayaquil, the first sync-sound motion picture of the Ecuadorian cinema that in 1950, that became a big hit. But it did not start up a new trend. It is that, in Ecuador, until now, very few films, were actually produced and the country had one and only ambassador, Camilo Luzuriaga, whose work was shown abroad, moderately, in the Nineties. But here as elsewhere new technologies (digital), have made filmmaking much more accessible to new talents and that is one of the reasons why film production has picked up the pace, but in the spur-of-the-moment, without any real structures.

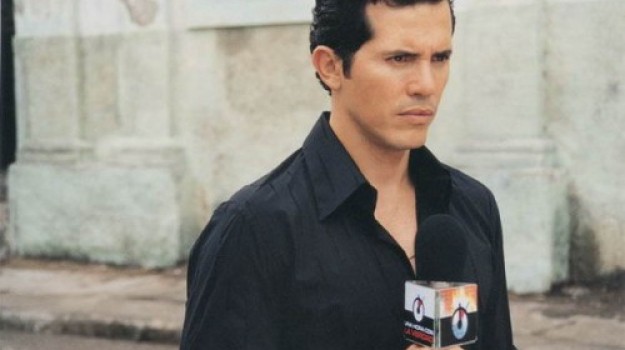

The tide has turned. The government has decided to develop and encourage this awakening, by creating the much-needed Consejo Nacional de Cine to promote and structure local production. First a cinema school in Quito, then another one just inaugurated in Guayaquil provide professional training to technicians, producers, actors, and filmmakers. Currently an independent structure, Ocho y Medio, struggles to put a stop on multiplex omnipresence and Hollywood commercial productions by programming and screening through its theater network innovating programs.These changes will soon bear fruit. But already, the Ecuadorian cinema is shown abroad Crónicas, by Sebastián Cordero, whose co production with Mexico gave him the opportunity to work with actors such as John Leguizamo and Leonor Watling, representing Ecuador in the Festival de Cannes, in the selection Un Certain Regard; Que tan lejos by Tania Hermida, benefited from a French distribution; other filmmakers, such as Juan Martin Cueva, Daniel Andrade or Victor Arregui, saw their work shown abroad, but are stilt to be discovered.

To propose a program around the Ecuadorian cinema, today, is more of a promising challenge, than a retrospective. The structuring of the Ecuadorian cinematographic landscape let us suppose that the number of films produced each year will increase in an exponential way during the next decade. In order to help meet objectives and build up a strong national cinematographic identity: it is necessary to consider, as of now, the premises in order to make a stand on the future.

Jean-Philippe Tessé

Programmer

Until one decade ago, the cinema in Ecuador was a mystery for the world. As it happened in many countries of Latin America, the history of the Ecuadorian cinema was a dramatic story of birth, death, resurrection and rebirth. Prolonged periods of production absence are alternated with rare moments where some film productions falsely announced the definitive take-off of our national cinema. Only for the last ten years has it been possible to speak about constant development and growth. In spite of this, the cinematographic activity keeps on struggling between the limitations of reality and a potential future.

Indeed, today the Ecuadorian cinema crosses its better moment. There has never been such a wide range production, distribution and institutional help. During this ongoing decade over 20 feature films have been produced, a number superior to that reached throughout the whole twenty century. For the first time, Ecuadorian films reach representation in international film festivals such as Sundance, Venice, Cannes, and Rotterdam. Ratas, ratones y rateros (1999) by Sebastián Cordero placed Ecuador in the crest of the so-called Latin American cinéma wave and constituted a paradigm for the emergent Ecuadorian filmmakers. Que tan lejos (2006) by Tania Hermida reached an unusual success in the national ticket office thought a humorously ironie picture on national imaginary. In the 2006, the «Ley de fomento del cine nacional» (National Film DevelopmentLaw) is approved and the «Consejo Nacional de Cine» is created with which the State for the first time assigns public founds in order to stimulate cinematographic activity. According to this organism’s estimations, three feature films will be produced per year.

In this emergency panorama, there would seem to be two trends that corne into play. An innovating one committed to an ongoing aesthetic and concept change differing from the sporadic and old cinema of the Eighties. A more conservative trend tries to resuscitate a prefabricated cinema based on social realism and nationalistic issues. On one side, the cinema seems to be trapped between a permanent go back to past aesthetic that includes a smug loyalty to traditional folkways and mores and an anecdotic cinema. Films such as Sueños en la mitad del mundo (1999), Un titan en el ring (2002) and 1809-1810. Mientras llega el día (2005), Que tan lejos (2006) summarize this tendency.

On the other hand, Ratas, ratones y rateros (1999) opens a generational, thematic and aesthetic breach within the Ecuadorian cinema. With adrenalin realism, this film questions the statute of a traditional social cinema and generates a getaway from established approaches on local reality. With this precedent, arises a new generation of filmmakers and films that rival with national cinematographic tradition. These films bring up a thematic diversification in our national cinema and share individual crisis and collective identity issues. Just to mention some : Alegría de una vez (2000), Maldita sea (2001), Fuera de Juego (2003), Crónicas (2005), Esas no son penas (2007), Cuando me toque a mí (2007).

Although the Ecuadorian cinema continues debating with its reality – national, factual and limited- there is a real cinematographic agitation that allows us to imagine the future. A latest generation of filmmakers who have made short- films their horse of battle, allow us to recognize the outcomes of the Ecuadorian cinema. For these young newcomers, cinema has stopped being the impossible testimony of a national identity, to transform itself into a project guided by desire. Social reality and cinematographic realism are crackling and let us imagine an emerging Ecuadorian cinema. L’Objetiv (2002) by Pancho Vinachi, Silencio nuclear (2002) by Iván Mora, El Correo de las horas (2003) by Sandino Burbano, Bifurcando la mirada (2006) by Federico Koeller, A la caza del rey (2007) by Patricio Burbano, Invitación a Sepelio (2007) by Marco Rodríguez, Emilia (2007) by Caria Valencia, Despierta (2008) by Ana Cristina Barragán announce an Ecuadorian cinema to come.

Christian León

Ecuadorian Film Critic