Where do heroes come from? As an echo to the question, an image comes back to me, in all its obviousness at first, but then revealing its darker side – the brilliant opening shot of John Ford’s The Searchers (1946): the door of an isolated house opens onto the Indian desert to show a figure slowly coming towards us from the background, as we gradually recognize John Wayne who seems to be coming back from the dead. The expected and familiar image of a war hero coming back to his family and friends alters to suggest an obscure sense of tension. What happened? What reverse of fortune did he go through which could lead us to suspect that Ethan (John Wayne), whose brother’s name is Aaron, is not exactly the man we expected to see again? Could the disasters brought about by World War II have corrupted the mythical image of Ford’s wild west?

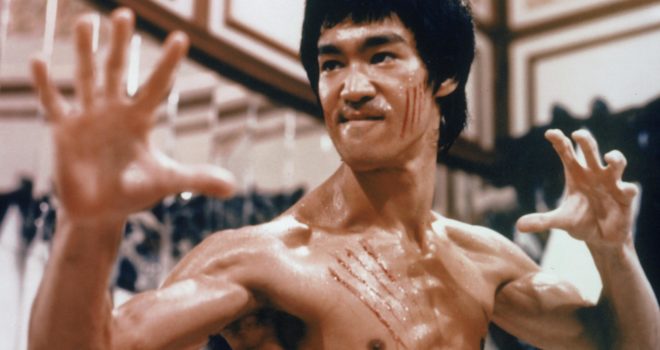

The superhuman, or plain human, figures whom we deem heroic have something in common: they exemplify the mark of ordeals, of challenges to death, to the order of things or to the sense of history. In our eyes, heroes are the emblems of extreme self-fulfilment. Their stories are like superimposed images of ourselves, the embodiment of an imaginary feat of our human condition which actualises itself, adapts, travels, reinvents itself through time, territories and cultures. The hero’s selfless actions for the benefit of higher values – a so-called ideal – make him overcome his condition (he often is a man of the people) and become the intangible sign of our need to admire, a sign which in itself is enough to stimulate the narrative. Beyond the expectation and the clichés which often appear under the guise of answers, how specific is the hero figure in films? Or, in simpler terms, how does cinema manage to create heroes on its own terms? While the hero notion is often overused and exploited as an efficient means to glorify the dream factory, the presence of heroes on the big screen sometimes generates proper film ideas and contributes to a fresh and active understanding of the world. Heroes inform us as much about the values of an era as about the concerns which that era struggles with. And this is not incompatible with entertainment. For instance, no one extols the power of a trained and efficient body like Bruce Lee. Lee operates a singular fusion between the actor and his double, the character he plays, in a tumultuous and cult imagery which his biographical legend entertains up to a certain degree of confusion. Getting one’s own back on America, so to speak.

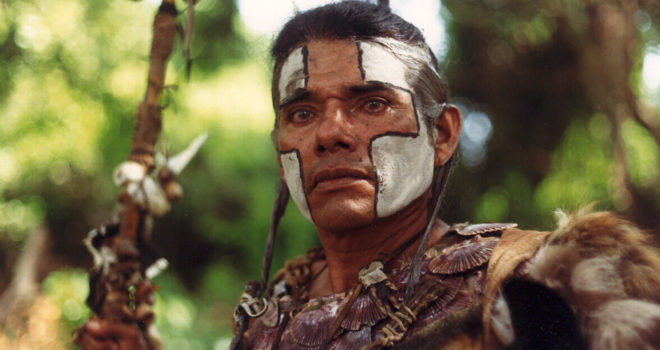

A samurai flanked by a princess and two fools (Akira Kurowasa’s cinema has numerous characters like these), a 16th-century Spanish explorer, a fearless teenager, a Brazilian contract killer who takes sides with the people, a woman fighting female genital mutilation, an Israeli film-maker wrestling with founding myths and today’s violence, the fate of four Mexican peons demanding social justice and joining Pancho Villa’s troops… The aim of this programme is to make the hero idea travel through an eclectic body of films, from action films to historical and collective epics, from lacklustre personal destinies to the most significant changes. In spite of differences nobody can miss, this is a way to assert how much each of us needs to share the life of one hero or another, even for a brief moment.

Jérôme BARON