Compared to the other countries where cinema was quick to thrive and where a long tradition of popular cinema exists, Japan stands out in that one of its cinema’s historic upheavals – equivalent to France’s New Wave – did not occur outside its film studios but rather inside, and also in that this upheaval took almost twenty years to fully mature.

Thus, Nagisa Oshima and Kijû Yoshida, the radical and emblematic “auteur” filmmakers of the post-war generation and standard-bearers of the “Shôchiku New Wave”, began their careers, as the movement’s name suggests, making films for the famous studio, which was also where Yasujirô Ozu spent his entire career. After leaving Shôchiku, Oshima and Yoshida founded their own production company and filmed with even greater freedom, while those filmmakers who stayed with the studio were required to carry on making films adapted to the new tastes and mores of the time, thus bolstering the established system. The map of Japanese cinema in the 1960s and 1970s is split between two poles: on one side, independent productions receptive to revolutionary dreams in search of new aesthetics, and on the other, an internal, relative revolution led from within studios, who in fact owed their survival to these developments. Yet the growing influx of skills from outside the film industry and their lack of studio experience, as well as new sources of financing in the form of capital invested by the music industry, talent agencies and publishing companies, caused the system to collapse and hastened the transition to a post-studio era in the late 1970s. Of all the first-generation filmmakers to emerge during this period, Shinji Sômai, because of his exceptionally creative talent, probably produced most impact not only on cinema audiences but also on later Japanese filmmaking.

In the 1970s, Sômai was temporarily employed by Nikkatsu, which had gained a second lease of life producing erotic, or so-called roman-porno films. The wealth of experience he gained during these years marks him out from other filmmakers of his generation, such as Yoshimitsu Morita or Kazuki Omori, who went directly from their end-of-studies films to work in the commercial film industry. Sômai also trod a different path from those who officially joined Nikkatsu and began their career with roman-porno films, such as Kichitarô Negishi or Toshiharu Ikeda, the last representatives of the studio generation. After some hesitant comings and goings at Nikkatsu, Sômai finally made his filmmaking debut with The Terrible Couple (Tonda Kappuru, 1980), his first film with the talent-agency-backed production company, Kitty Films. Striking the “right balance” in this bipolar landscape of Japanese cinema, Sômai emerged from the middle ground of what could be termed the no-man’s land of the post-studio era. This ambiguity of his origins, due to the specific circumstances of Japanese cinema at the time, means that as a filmmaker he is unclassifiable: his films are much too artisanal in character for him to be considered as an “Auteur”, but much too artistically sensitive to simply relegate him to the rank of an adroit image-maker.

Sômai did not receive sufficient support from the studios, but neither was he truly independent. So he navigated through almost all of the historic majors including Daiei, Tôhô and Shôchiku. In parallel, he collaborated with the Director’s Company, a production company created by other filmmakers of his generation. He also experimented with new, more modern production structures, headed by television channels, advertising agencies and publishing companies. This ability to adapt enabled him to make thirteen feature films and one television film during the two final decades of the twentieth century – his filmmaking started in 1980 and ended in 2000 exactly…

Read more

However, as the rights to these thirteen films are dispersed among many different companies, it is now difficult to organise large-scale retrospectives on Sômai or bring out a DVD edition of his complete works, even in Japan. Sômai was also one of those who care little about receiving acclaim as an “auteur” or gaining international recognition. People who knew him agree that it was this spirit of contradiction along with his eccentricity that enabled him to seduce all who met him. He thus paid only moderate attention to the fact that Bernardo Bertolucci and Nagisa Oshima showered high praise on Typhoon Club (Taifû Kurabu, 1985), that Luminous Woman (Hikaru Onna, 1987) and Moving (Ohikkoshi, 1993) were selected respectively for the 3 Continents Festival in Nantes and the “Un certain regard” section at Cannes, or that Wait and See (Ah, Haru, 1999) obtained the FIPRESCI Prize at the Berlinale. In his lifetime, therefore, he was barely recognised internationally as an “auteur” with his own coherent style.

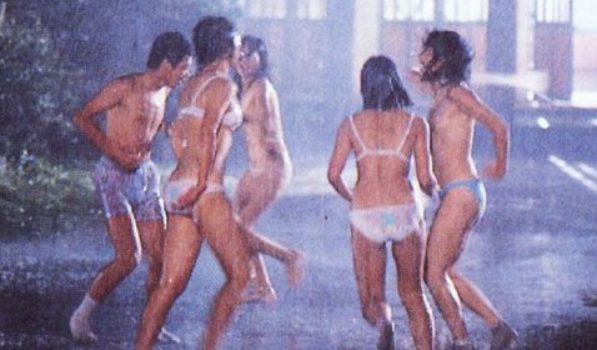

Nonetheless, Sômai’s influence on home ground was colossal. At the outset of his career in the 1980s, auteur films from the world over were bursting onto Japanese screens. Myriad original and landmark films were projected in Japanese film theatres, placing the Nippon capital on a par with cities like Paris or New York. For reasons other than the golden age of the studios, cinema was now in fashion and became a cultural phenomenon spearheading all that was modern. It was in this setting that Sômai made his first films, which go beyond the mould of major-distributed “teenage movies”to reveal the exceptional style of an author whose long shots were to become his hallmark. His films swiftly became cult films for a new cinephilia that was emerging at the time. Sômai was also reputed for his highly persevering direction of actors, who had to rehearse their scenes endlessly before shooting began. Sômai was regarded as a master in the art of training young debutant actresses who acquired star status after completing their exacting apprenticeship. Sômai thus catapulted many talented actresses into the spotlight, starting with Hiroko Yakushimaru who featured in his first two films, Yuki Saitô, and Yûki Kudô, who was later directed by Jim Jarmusch. Acting in one of Sômai’s films enabled them to move from their status of pop teen idols to that of star – while, in the screen’s mirror, they embodied teenagers on their way to adulthood. Young filmgoers identified with such actresses, juxtaposing the characters’ faces with their own until they became interchangeable, watching them with a complicit and understanding eye as they themselves matured. This is why so many Japanese fans remember these years with emotion, pointing out that “Sômai was their entire youth”.

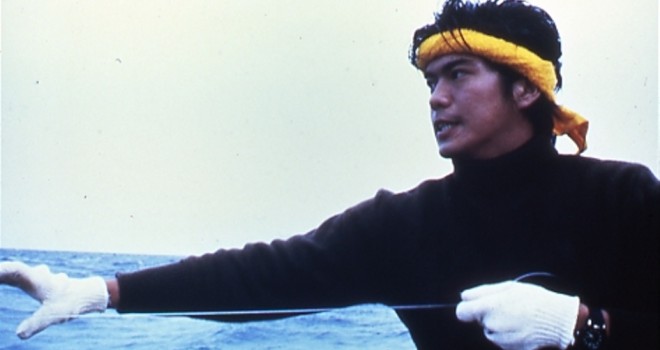

As the record success of his second film, Sailor Suit and Machine Gun (Sêrâfuku to kikanjû, 1981) confirms, Sômai enjoyed huge popularity with the public, but those who were most stimulated by his films were unquestionably the young filmmakers of the time. I would venture to say that not one of today’s best-known Japanese filmmakers has remained immune to his influence. Very early on in Sômai’s work, long shots became his characteristic stamp: most of the time, these exceed the time necessary for the narrative and use such vast travelling shots that we sometimes wonder how they have been filmed. This atypical, extraordinary style infused many budding filmmakers of the time with the desire to make their own films. Thus, the work of today’s outstanding Japanese actors shows its true nature when seen as a critical reaction to Sômai’s work. At the outset of his career, Kiyoshi Kurosawa had a privileged relationship with Sômai since he had worked as assistant director on Sailor Suit and Machine Gun. But despite a real and secret fascination with Sômai’s style, Kurosawa describes his elder as “excessive” to the point of being a counter-example and, thus, intelligently manages to spare himself an “accursed filmmaker” status. Similarly, Shinji Aoyama called on the skills of Masaki Tamura, director of photography on Sômai’s more radical film, P.P. Rider (Shonben Rider, 1983). In the course of their collaboration, Aoyama has in turn explored the potentiality of long shots in his own manner. In the same vein, knowing Sômai, it is not surprising to find Tomokazu Miura, the unkempt teacher of Typhoon Club, in the lead role of Nobuhiro Suwa’s M/OTHER. In another of Suwa’s films, Yuki and Nina, we again understand why a young girl, who is obliged to grow up too quickly following her parents’ divorce, goes off alone deep into the forest, like the young heroine of Moving. And Sômai’s influence even extends as far as the world of animation, as is shown by the many school scenes reminiscent of Typhoon Club, which subtly depicted the psyche of youngsters at the age of puberty.

This said, the often extraordinary character of Sômai’s long shots and travelling camera must not distract us from what typifies the essence of his work to an even greater extent. As I mentioned earlier, his films bear the legacy of studio filmmaking as much as that of films from the post-studio era. Certainly, Sômai secretly perpetuates the rich heritage of Nikkatsu. Despite Nikkatsu’s seniority and prestige – this year, the studio celebrates its hundredth year of existence – its entry onto the post-war film market was hampered in different ways by the other big studios. To revive its production business (1954) and meet audience expectations, Nikkatsu focused on producing innovative action films that broke with tradition, featuring totally unmoulded young actors found through auditions. As I mentioned above, when Sômai joined the studio’s ranks in the 1970s, Nikkatsu had already shifted to producing roman-porno films. Sômai chose a good part of his team from among the studio’s emancipated, veteran professionals – those who refused the constraints of realism in the narrow sense espoused by many mainstream films but contested by many of Nikkatsu’s roman-porno and earlier action films. In fact, it is difficult to imagine that Sômai could have filmed with such freedom without the presence of Kei Ijichi, a former assistant director at Nikkatsu who went on to become a producer with the studio’s shift to the roman-porno genre. Likewise, if Sômai’s work shows consistency even though he almost systematically changed his director of photography from one shoot to another, it is largely thanks to the contribution of Hideo Kumagai, who was lighting director on most of his films. Finally, if Sômai manages, right from his first film, The Terrible Couple, to define his own singular style based on long shots, it is certainly thanks to the talent of his director of photography, Nobumasa Mizunoo, who had previously worked with Chûsei Sone on Angel Guts: Red Classroom, the roman-porno masterpiece for which Mizunoo had already filmed some stupendous long shots. Sômai successfully drew the best out of these technicians, whose personality and skills were put to lesser use in the studios. The potential of these talented men was thus liberated in the no-man’s land of the post-studio years. In Tokyo Heaven (Tôkyô jôkû irasshaimase, 1990), the cinematic space created and exploited by Sômai consisted of a luxury building’s two upper storeys linked together by a rope ladder. Although this film has a rather dismal critical reception even today, it is an extremely precious work inasmuch as it is one of the last testimonies of an era when it was still possible to build on the vestiges of the studios. For his later works, Sômai accepted with aplomb that the techniques and know-how that had enriched his filmmaking were being lost. As a result, he gave his films a more modest scope, more adapted to the modern age, yet still making a point of preserving a certain “studio spirit”. As a result, Sômai tried to branch out in new directions. However, these were increasingly thwarted by changes in technology and audiences: the obscurity of film theatres was becoming as unnecessary as celluloid film. It was in this context that Sômai made the most classical of all his films: Wait and See. Far from representing a step backwards, it can in fact be considered as an astonishing achievement.

Sômai crossed this moment in the history of Japanese cinema – the post-studio era – at high speed. He himself disappeared prematurely after exploring the limits of what analogue film had to offer, just as it was being ousted by the advent of digital film. Seeing all of Sômai’s films today, exactly ten years after his death, should enable us to gauge what cinema has lost in the meantime and what it has newly gained. In this sense, it is an undertaking that is both heartening and nostalgic.