The question of genre cinema and its evolution is not extraneous to cinephile concerns. While the Festival 3 Continents has always programmed such films sparingly, the selection has been made with the same unswerving rigour as for “auteur cinema”. And we are willing to wager that this in no way hampers the entertainment value of such films, and even helps to pinpoint, among the profusion of mainstream films, those that stand out in the artistic landscape. This is not as straightforward as it seems. Certainly the hefty resources available to commercial cinema help to maintain its spectacular side, but they are just as essential to the cinematic ideas that these films develop and carry. Genre is only an alibi in the worst case (but also the most frequent). In the best case, it is a privileged conduit, a condition of the art. In this sense, mediocrity is just as recognisable in a cinema that displays the seriousness of its approach as the genius sometimes expressed in films that, under the pleasant guise of entertainment, outstrip genre cinema in their thinking and mastery of form. On this fundamental point, the history of cinema as exemplified by Hollywood is enlightening. None of us can forget that among the chosen names of the famous “authors’ policy” articulated by the Cahiers du cinema we find, under the same ensign of the art of mise en scène, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Howard Hawks, and Carl Theodor Dreyer, Luis Buñuel, Roberto Rossellini, Jean Renoir…

Hong Kong cinema is internationally famous for its kung-fu and crime films, but much less so for its plethoric output of love stories or comedies. In Bruce Lee, it possesses the original icon of martial arts cinema, a genre made respectable by Chang Cheh and Liu Chia-liang, in the wake of King Hu, while others, such as Tsui Hark, developed its potential even further in the early 1980s (Tsui Hark also produced John Woo through his company, Film Workshop). From the 1970s until the end of the 1980s (which also saw the first steps of Stanley Kwan and Ann Hui, and Wong Kar-wai’s on the international scene), Hong Kong cinema experienced a remarkable economic boom and intense artistic vitality, which carried over into the early 1990s.

When Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai founded Milkyway Image Limited in 1996, the context was already more uncertain. The Hong Kong film industry had lost ground locally and its influence in the neighbouring markets of Taiwan and South-East Asia was in decline. On the eve of the retrocession of the British colony to China – taking on the status of “special administrative region” – deep concern loomed over the main Asian and international financial centres. Whereas part of Hong Kong’s production activities had already been relocated to the People’s Republic during the 1980s, the main concern was how the official declarations of making the territory into a key economic component of the Chinese system would materialise. In this tense setting, some well-known talents were given the opportunity to pursue their careers in Hollywood, which was looking to give fresh blood to its action movies. Among them were actors such as Michelle Yeoh and Chow Yun-fat, but also filmmakers including John Woo (Hard Target, 1993, Broken Arrow, 1996, Face/Off, 1997, Mission Impossible 2, 2000), Ringo Lam and Tsui Kark, who made two failed attempts to work with Jean-Claude Van Damme (Double Team, 1997, Knock Off, 1998) then promptly returned to Hong Kong where he again found inspiration again with Time and Tide (2000).

Read more

At the time Milkyway Image Ltd was created, neither Johnnie To not Wai Ka-fai enjoyed an established international reputation. Nonetheless, both were seen as having strong personalities. Well-versed in the efficient “made-in-HK” production methods that they had learnt working with film and television, their contributions to Milkyway are as complementary as their roles are interchangeable : scriptwriter, filmmaker, producer. Moreover, their experience in television most likely made the two partners well aware of their contemporaries’ expectations. With To and Wai permutating their filmmaking roles, Milkyway productions exhibit, with a kind of symmetry, a striking permeability to very contrasted film styles, stretching from the most exacting to the most popular. More interestingly, the films seem to accomplish a novel blend of proven professionalism (Johnnie To’s input) and delirious sophistication (Wai Ka-fai’s input) that soon became the Milkyway’s hallmark. Their approach is underpinned by a rigorously pragmatic vision. The eccentricity of films such as Too Many Ways to Be No.1 (Wai Ka-fai) or The Odd One Dies (Patrick Yau), both made in 1997, is counterbalanced by films that were more certain to meet with the public’s approval and were often made by the founding duo. Needing you (2000), a frivolous comedy starring Andy Lau and Sammi Cheng, was a resounding box office success (local receipts totalled HK$35 million) and is a perfect illustration of their system’s cornerstone. Johnnie To very carefully maintains this balance as it is what guarantees not only Milkyway’s longevity, but more importantly its independence and daring. Although for most of us shoot-outs are among the more memorable scenes of Milkyway films, in its frenetic race to produce (seven features in 2001 alone) the company runs all the risks that it is allowed by an expertise that is, in fact, not so ballistic.

Johnnie To has often confessed that he prepares and then views his films as exercises, omitting to say which ones he considers successful. We need to read between the lines of these comments and recognise, behind the forced casualness, a degree of modesty and an insistence on rigour. Milkyway can be seen as a laboratory where people continue to learn their trade on the job. Each individual encounters other skills that cluster around the hub of the founding duo in order to confront different inspirations and temptations. Here, (commercial) genre cinema affirms that it is part of a tradition but is constantly seeking to push back the conventional limits. The contributions of all are mustered in a game that actively welcomes new talents. While the team is putting together a fast-assembled, money-making film, many hands are also busy working on a prototype project, where no one knows what the result will look like until the very end. Help!!! (2000) was shot and edited in twenty-seven days whereas it took several years to make PTU (2003) and Sparrow (2008). Job positions change or are shared by several people, technicians serve as actors, actors come together, separate and meet up again. They are used to each other but their habits are also challenged by each following film. The position of Lam Suet, the main supporting role in some thirty Milkyway films, is interesting on this count. He often gives the impression of being both spectator and actor in the situations his characters experience. His presence provides a reference point and testimony, a lookout post, ensuring that all is going smoothly before everything goes off track.

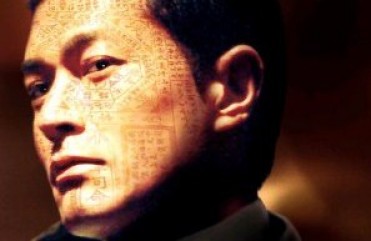

We find a host of tricks, a great deal of intuition and seeming pleasure in the way that Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai orchestrate Milkyway’s intense creative activity. Many of the films show this quite clearly and joyfully exploit these aspects in different ways. To cite just two of many examples, in Fat Choi Spirit, a comedy where gaming is concretely portrayed through the characters’ addiction to mah-jong, Johnnie To brings face to face two of his emblematic actors, Ching-wan Lau and Andy Lau, previously poles apart from each other: hyper-masculinity on one side and anti-heroic romanticism on the other. In Expect the Unexpected, two gangs are on the loose, one clumsy and inexperienced, the other efficiently professional. It is not hard to guess which one wins out and stirs up the most trouble in its path. With a disconcerting sense of enjoyment, the scenarios thwart our expectations and slip into different styles with no prior warning as in Where a Good Man Goes (1999), a film too often overlooked, or Yesterday Once More (2004), also the title of a song by the Carpenters. This is not so much a search for originality at any price, but a matter of giving form to a view of the world where things are never fixed once and for all (especially not in the action genre cinema), where everything is open-ended and often double-sided. Behind the apparent makeover of a Hong Kong triad film faintly echoing Coppola’s Godfather, Election 1 (2005) and 2 (2006) are biting political and historical allegories that reveal a more literary strand in Johnnie To’s work. This aspect is reaffirmed in his last film released in France, the remarkable Life Without Principle (2011). Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004) seem impossible to classify; none of the known film genres seem to fit these two films, where dark, slapstick and even mystical tones hybridize or neutralise each other. In the first, the Cary Grantesque actor and Hong Kong superstar Andy Lau undergoes endless metamorphoses, while, in the second, Louis Khoo and Aaron Kwok abandon kung-fu for judo and regain enough physical and moral integrity to bring Johnnie To closer in substance to Akira Kurosawa. Although extravagance is triumphant in both films, it also confirms the coherence and intelligence of the Milkyway system’s guiding purpose. Genre cinema, which is popular by definition, becomes a privileged place for questioning the traditional foundations of a society at the crossroads of multiple influences and racing headlong into unavoidable modernity. Changing appearances or hilarious transformations, fratricidal clashes, wavering love stories, reversals of situation, a sense of belonging and dedication or personal choice, violence and humour, supernatural power or handicap, full of twists, distance, dissonance, all point to the defining of a torn almost schizophrenic identity.

From Cheng Siu-keung (a brilliant director of photography) to Bruce Yu (art director and costume designer), from Yau Nai-hoi (who has penned over twenty scenarios and directed Eye in the Sky in 2007) to Ding Yuin Shan (production manager and street photographer), Milkyway Team members regularly stress the importance of the choice of location. While locations actively contribute to the authenticity of the action and the dramatic stakes, cinema also makes its impact on the city’s saturated bustle. It unfolds in the urban space and reorients timescales, becoming the city’s double so as to better reflect it. Both insular and continental, Hong Kong is in no way reduced in Milkyway films to a decorative function or relegated to a supporting role. The city is necessary to a cinema that lovingly maps its post-1997 changes: between day and night. If Milkyway is viewed by the world as embodying the only real driving force in Hong Kong cinema today, the stylised quality of the films it produces sustain this fascination for a dense and contradictory world: terrifically and terrifyingly alive.

Jérôme Baron