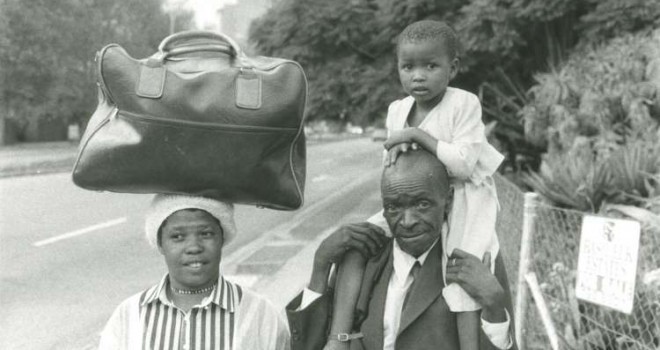

In the thematic section Vivre la ville proposed to last year’s festival-goers, we programmed District 9 by South-African director Neil Blomkamp. Coproduced by Peter Jackson, this science-fiction feature shows refugee aliens resembling two-legged giant shrimps cooped up in corrugated-iron huts much like those in the townships and peacefully awaiting a solution to their plight (the authorities mention deportation). Here, a digression via the science fiction genre and its artifices allows cinema to steer reality between a past (the film opens in a false documentary mode with archive footage) and a future (a cataclysmic Utopia) that seems possible. The uchronia of District 9 lies in the film’s clear intention to place some of the social, historical and ideological realities of the Apartheid years in a future that is equally if not more absurd than actual history. The climate of urban guerrilla conflict, which unfortunately is not pure fiction, projects an ambivalent image of present-day Johannesburg, where the film was set. It was undoubtedly on recalling District 9’s crazy and almost paranoid representations that the idea emerged of putting together films (features and documentaries) that could be watched essentially as documents about a country. The question was which specific images, fictions or imaginaries in South Africa’s national film output would be able to recount the half-century-long history of racial segregation and the system that legitimatised it? As District 9 hints, sometimes a little heavily, abolishing the system does not induce an immediate switchover to another age. Contemporary South African cinema clearly shows that the consequences and relics of this system are still deeply anchored. We thus need to pinpoint the eventual pitfalls that come into play if one is tempted to take a retrospective look at these years. The first pitfall lies in the potentially spectacular nature of the context, whereas what really imports is to show the cinema’s ability to bear witness and provide a filmic reflection on its subject matter. The second, on the contrary, relates to the limits of (over)exploitating anti-apartheid motifs as an antidote or operation that can purge and re-legitimise cinema – this can be driven either by the kind of sincere intentions that rarely make for a good film, or by commercial instrumentalisation, or even both.

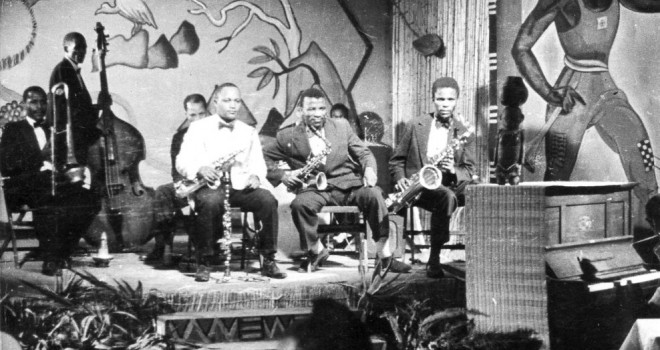

Although South African cinema is one of the most productive on the continent, the fact remains that it is still scarcely known, and the pre-1990 films even less. What then has really characterised the situation of South African cinema? What are the real drivers of the directions and revised ambitions of its Anglo-Saxon-style film industry? Our programme does not offer detailed answers to all these questions but instead attempts to plot out South Africa’s relations with its cinema and provide some milestones that will hopefully afford greater understanding. What we can certainly say is that the first impact of segregation is to compartmentalise cinema, and the first impact of ideology is to weaken its expression or often impede it. Established order and capital have always got on well together and, united, they provided funding for a national film industry for Whites only and mostly in Afrikaans – setting aside the large but mediocre Bantu film output that took off in the 1970s. For many, film production from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s holds little interest – except perhaps with respect to the structural changes in production finance. Nonetheless, the general public got enough out of these films to give commercial cinema, and later community cinema, a relatively stable attendance record throughout the whole period. There was hardly any thrust for these films to address wider or even international audiences. While the South African Blacks were excluded from power and administrations in their home country, the Whites entrapped themselves in a closed world and a system of representation turned in on itself. The Afrikaner society had become the sole but never problematized reference for a cinema that shied away from any critical engagement. What mattered instead was to flatter a conservative ideal bound up with a moral and religious principles and the purity of a language and of the race that spoke it. In the 1960s and 1970s, the films of Jans Rautenbach (Die Kandidaat, Katrina) and Emil Nofal, along with the films of Manie van Rensburg and Ross Devenish (whose film, The Guest, was awarded at Locarno in 1977), began to displace some very rigid references by introducing a more noticeable reflexive dimension into their films and, above all, by recognising the reality of a multicultural and multiracial society. In his book, The Cinema of Apartheid, Keyan Tomaselli explains that the National Party ideology had been determined by the blind denial of history’s inexorable advance, and that toughening this ideology even further in the mid-1980s, during a period that saw growing protest, merely delayed the inevitable. For the whole world this inevitable had a name: Nelson Mandela…

Read more

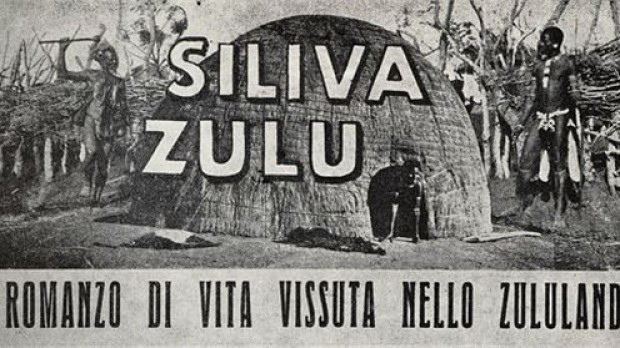

What we are trying to do by looking back from today – thirty years after the end of Apartheid – to as far back as Siliva the Zulu (1928) by the filmmaker and ethnologist Attilio Gatti, is to retrace a tormented and complex history and identify its milestone films. Indeed, Gatti’s film could be seen as a “first contact” film, the start of a clumsily biased and ethnocentric gaze on indigenous culture. Then come the films whose forms and discourse resist the segregationist ideology (Michael Scott’s Civilization on Trial in South Africa (1949), the first documented “protest film”, Zoltan Korda’s Cry the Beloved Country (1951) or Lionel Rogosin’s mighty Come Back, Africa (1959) or the much later films that epitomise the period just before the abolition of Apartheid, such as Oliver Schmitz’s Mapantsula (1988) (banned nationally at the time it was made). Yet, the contradictory representations depicted by Peter Davis, Martin Botha or Keyan Tomaselli, each in their own way and with convergent voices, convey the image a country in permanent agitation but where nothing ever really changes.

To conclude, this Festival des 3 Continents programme, which is part of the France-South Africa Season, will home in on the contemporary period with two films co-produced by the two countries, South African Chronicles (1987) from the Ateliers Varan et Ramadan Suleman’s Zulu love Letter (2004).

The “Produire au Sud” Workshop will also be welcoming to Nantes three filmmakers with South African projects, as well as the young producer, Elias Ribeiro, who in 2013 co-produced the exciting documentary Jeppe on a Friday, named after one of Johannesburg’s districts. So, it is with this film that we hop onto today’s train.

While South African cinema is still based on a very American-style conception of its film and television industry, right down to its aesthetic forms, it also hints at other voices and signs that could open the door to some original work not too far ahead. It is important that we hear and relay these, and that we plan in advance for other exchanges in a not too distant future.

Jérôme Baron