As the Chinese Film Archives open up their collections, we are becoming increasingly aware of how diverse the country’s film production really is. Not only is there a diversity of production locations and styles but also, more broadly, of cultural heritages. Yet, what is striking, over and above the wars, ideological struggles and political schisms, is its continuity: the fifteen films or so made between 1931 and 1950 and screened by the Festival des 3 Continents reveal to us some of the great filmmakers of the first half of the twentieth century, enabling us to follow not only their artistic trajectories but also their cinematographic peregrinations between Shanghai, Hong Kong and Beijing.

These three cities have a dual presence: Shanghai and Hong Kong are places where the filmmakers live and work, but they are also the settings for a good number of Chinese films. The ties created between the protagonists, storylines and cities show that they are much more than simple sets; they are in fact fully fledged characters, whose portraits are drawn by a commingling of the filmmakers’ real-life experience and imaginary projections.

First of all, Shanghai. Shanghai was to become China’s first film capital. It was in this city, divided between the Chinese area and the concessions under Western administration, that the first film production companies were set up in the early 1920s. It was also in Shanghai, a modern metropolis with its tramways, its illuminations and the imposing art deco facades along The Bund, that prestigious film palaces were built, vast and luxurious. Until 1941 when the War of the Pacific put a temporary halt to trade with America, the Shanghai film theatres screened everything, especially everything produced by Hollywood, be it silent films, talking films, short, long, feature films or newsreels… and it was from these films that Chinese filmmakers drew their first lessons in filmmaking. They borrowed genres, visual codes and acting styles but adapted them to the technical constraints of a cash-strapped industry (talking films only became mainstream in China after 1935) and to the demands of the local audiences, who were highly sensitive to the stakes of cultural nationalism. The Peach Girl (Tao hua qi xue ji) made by Bu Wancang in 1931 thus took up Griffith’s art of melodrama, much appreciated by Chinese audiences (Way Down East was a great success in China), at the same time rooting it firmly in issues relevant to the Chinese society of the time. Many films from that epoch very openly cite and hijack American works. Song at Midnight (Ye ban ge sheng) is a good example of this: director Maxu Weibang drew inspiration from The Phantom of the Opera (R. Julian, 1925) and Frankenstein (J. Whale, 1931) to make a genre film adapted to the Chinese context. Made on the eve of Japan’s invasion of China, the film conveyed a patriotic message and explored the resources of cinematographic sound using sound effects and songs. Under the cloak of entertainment, Chinese films also very often seek to raise awareness, denounce ills or mobilise energies in the context of a vulnerable young nation in crisis, exposed to the economic and territorial appetites of the Western powers and Japan.

In the China of the 1930s,Shanghai is also the city in which the two aspects of modernity come face to face: Westernisation is one of the results of colonial domination, and technological progress goes hand in hand with its different ills: whatever form it takes, it implies the exploitation of the weak by the powerful. In films such as, At the Crossroads (Shi zi jie tou, Shen Xiling, 1937), The Goddess (Shen nü, Wu Yonggang, 1934), New Women (Xin nü xing, Cai Chusheng, 1935) or Fishermen’s Song (Yu guang qu, 1934), the city is portrayed as a place of ruin and despair, be it the fishermen’s poverty, the hardship of youngsters who nothing to do or the despair of young women struggling for their independence and dignity in a society that rejects them. Shanghai, with its ballet of trams or passing riverboats and its waltz of illuminations and cabarets is more than just a backcloth for the debasement of these ordinary folk: the city not only abuses them with its haughty and brutal modernity but also attracts them with hopes for a better future…

Read more

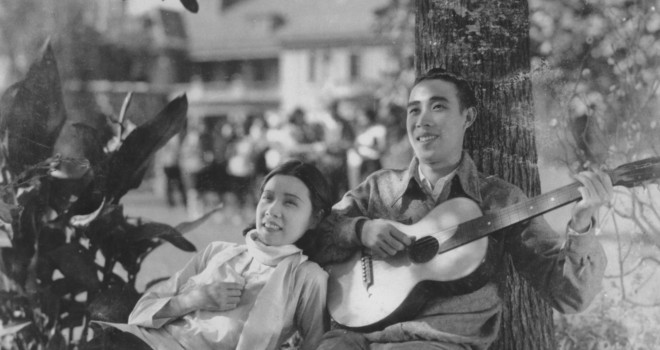

In Shanghai, as in the films produced there, the relationship with the West is ambivalent: the West is both a model and an enemy. And although the Hollywood reference was powerful, it was constantly being reshaped and spiced up with other influences closer to the political stances of many Chinese artists of the time. Cai Chusheng, for example, explained that from 1932 on (the year that Sino-Soviet diplomatic relations were re-established) he discovered Soviet films such as Road to Life (Poutiovka v jizn, N. Ekk, 1931) that strongly influenced his artistic approach and his determination to describe the sufferings of the Chinese people as authentically as possible. In At the Crossroads by Shen Xiling, another artist close to leftist circles, we can also detect the mixed and splendidly digested influences of American and Japanese filmmakers, particularly Ozu, in the way he blends slapstick and bitterness to describe the daily life of over-qualified youngsters struggling with unemployment and the economic crisis.

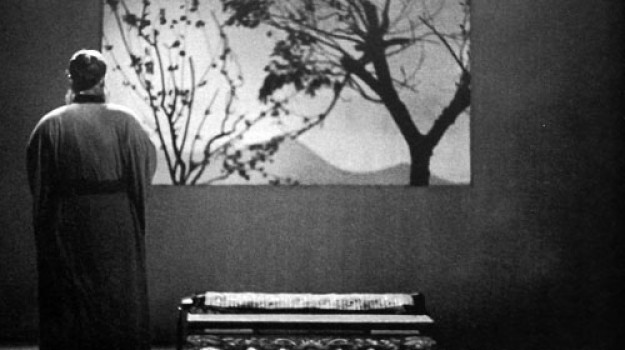

Although the filmmakers, and their audiences, were fully receptive to films from abroad, they nonetheless remained determined to give their work a Chinese identity that went beyond simply the choice of subject matter. Fei Mu was doubtless the filmmaker that took this approach the furthest as he explored the ways in which the traditional Chinese arts of poetry, painting and opera could enrich filmmaking. Three magnificent films point up the different moments of his itinerary. The now well-known film Springtime in a Small Town (Xiao cheng zhi chun, 1948) was the last work of this artist, who died a premature death, and is exceptional for its allusive, evocative and shifting register that functions much like the workings of a Chinese poem. We will also discover two of his earlier films in the programme. Filial Piety (Tian Lun, 1935) was made in singular circumstances, as its producer was keen that the film defend and illustrate Chinese culture in line with the ruling Nationalist Party’s conception. In fact, the film was one of the rare Chinese productions to be screened at the time in the United States, in the form of a reworked version entitled Song of China, which is also the only version to have survived. Yet, Fei Mu successfully sublimated the traditional moralistic storyline conveying the profoundly Confucian notion of filial piety by using an original approach to cinematographic art that owes much of its treatment of space to Chinese pictorial art: his frames comprise medium- and wide-angle shots incorporating scenic elements that shift the focus away from the central action, and his editing highlights a kind of flow and movement. Confucius (Kong Fuzi, 1941) also explores the evocative power of image and sound, and shies way from any kind of realistic mise en scène to compose a human portrait of the Sage against the backdrop of war.

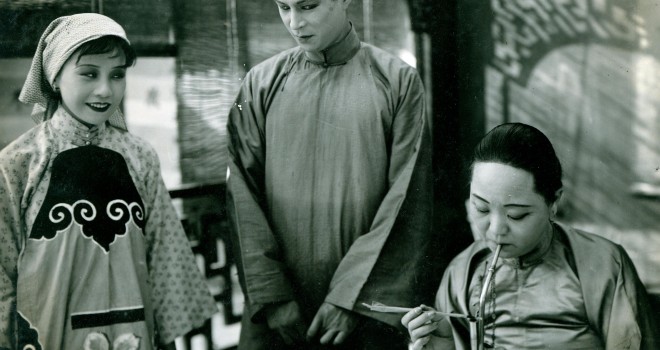

Confucius was shot over the year 1940, a period when Shanghai was partly occupied by the Japanese. The studios in which Fei Mu worked were at the time independent, but by the end of 1941, after Pearl Harbour, the situation had changed. The Shanghai film studios came under Japanese control and were merged into a single structure called Zhonglian. Many filmmakers, technicians and actors – and not the least among them – thus found themselves working for this one and only Shanghai studio. The studio made a few propaganda films that sang the praises of the friendship between the Asian peoples, as well as films in a variety of styles: period films, dramas and comedies, in which the artists tried their best to preserve something of their national culture. It was in this context that Zhu Shilin and Yue Feng, who had begun their work before the war, not only developed their talents but also trained younger people, some of whom were destined to become major filmmakers in Communist China. After the war, these two filmmakers, along with a hundred or so others, were the targets of repeated attacks accusing them of compromising with the enemy. To escape this witch-hunt, carried out at a time when the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists was stirring up hatred, they left for Hong Kong. It was thus in exile that they made Secrets of the Qing Court (Qing gong mi shi, Zhu Shilin, 1948) and the Flower Street (Hua jie, Yue Feng, 1950), both of which reconstructed a China of the past and very different from the China they had left. Set in the final days of the Manchu dynasty in the Imperial City of Beijing, Secrets of the Qing Court is a virtuoso super-production that features a masterful cast and affords a large place to women, as is often the case in Zhu Shilin’s films. The film ends on a powerful image that shows the people renewing their confidence in the Emperor of China: was this meant to convey a message of support to Chiang Kai-shek, who was then losing the war against the Communists ? This is at least how the Communist leaders understood the film when it was shown in mainland China in 1950: attacked by the press, it was hastily withdrawn from the screens and became a favourite target for Communist criticism. Flower Street looks back at the period of the Japanese invasion. In its description of daily life in a Shanghai street under the occupation, the film responds to the accusations of compromising with the enemy levelled against its director and some of the actors (including Zhou Xuan). Certainly, one needed to be out of China and far from the paroxysms of the civil war to dare such a nuanced and delicate description of this painful past and create such an un-ideological reconstruction of a period that was still fresh in people’s minds.

It was also fromHong Kong that, many years later, a nostalgic but also very well informed vision of the 1930s Shanghai film industry appeared. In Center Stage (Yuen Ling-yuk, 1992), Stanley Kwan retraces not only the final years of the career of one of the greatest stars of the time, Ruan Lingyu, who features at Nantes in three of her finest performances (The Peach Girl, The Goddess, New Women), but also the life of Lianhua, one of the largest film studios of the epoch and also the studio where many of the filmmakers screened at the festival worked: Bu Wancang, Cai Chusheng, Fei Mu, Sun Yu, Wu Yonggang, Zhu Shilin… a film that incites reflection on artistic transmission and legacies, and shows how far pre-war Shanghai cinema was to spread across the whole of the Chinese film world.

There are abundant resonances between Flower Street and This Life of Mine (Wo zhe yi beizi, Shi Hui, 1950), which was made in the same year but in a very different context – in Shanghai, in one of the rare private studios to be authorised after the advent of Chinese Communism. In both cases, the history of China and the major upheavals that the country experienced in the first half of the twentieth century are described at street level – the first film in Shanghai and the second in Beijing. Shi Hui, a great actor and director, delights in describing the life of Beijing’s ordinary folk, but he also shows how they are constantly abused whatever the political regime. The film closes on the triumph of the Communist Army: was the sun finally rising over the populations of Shanghai and Beijing, whose clashes and misfortunes the cinema had endlessly described for over thirty years? The fate of Shi Hui, who disappeared without a trace in 1957 after being violently attacked and treated as “right-wing” by the Communist press, gives a tragic answer to this question.

Anne Kerlan, Institut d’histoire du temps présent, Paris, CNRS.