Many programmes and selections have been highly reactive to the abundance of Latin American film output seen over the last fifteen years or so. One could even say that such sharp focus on the Argentine, Chilean, Mexican and Colombian cinemas is without precedent. Naturally, the Festival des 3 Continents has been participating in deciphering them for a good while now, but has kept a deliberate distance from the surrounding frenzy, which has sometimes been used for intensive catch-up sessions. There’s no denying the change in direction or the importance of the initiatives that have led these cinemas towards greater international recognition. More to the point, we are delighted with the most obvious outcome – the increasing regularity with which these films are shown on French screens. Yet, amongst this mass of filmmakers, we now need identify those that can be considered, with a little hindsight, to be building their work over time. Some of the films seem to derive from a conjunctural emulation honed by other elements that even more specific to the individual countries. This seems particularly noticeable in the Argentine case or in some aspects of Mexican cinema. There is also no denying the decisive role of the digital environment and its appropriation by the younger generations, spurred on by some iconic examples. Although these observations reflect the broad directions, the trends or modes at work in art house cinema are visible to all.

But taking a closer look at this Latin America, what is invariably curious is Brazil’s atypical situation, which is not due simply to its language difference or its specific geography. In this immense country of over two hundred million inhabitants (half of the continent’s total population), it seems that cinema has only ever found a temporary anchorage, as if it were evolving in an oblique relationship to social and cultural life. And yet several attempts at industrialisation have been made, which produced some one-off commercial successes (like the chanchadas) but more often ended in bitter failure (such as Vera Cruz in the late 1940s). Brazilian cinema – the cinema of Peixoto and Cavalcanti, from Rocha to the so-called Urdigrudi (underground) like Sganzerla and Bressane (A Erva do Rato, in 2008 competition) – seems to have made its presence felt as an art form only thanks to some accidental, marginal, provocative and experimental spirits. The temptation is to say that it is advancing in fits and starts, or against the tide, with the undeclared dream of paving the way to a unique local realism (this was one of Cinema Novo’s biggest achievements between the 1950s and 1960s) that is able to convey the diversity and wealth of what the country’s spirit of modernity embraces. From this viewpoint, the engagement of Brazilian cinema can be compared to that of the country’s great architects – Lucio Costa, Affonso Eduardo Reydi, Carlos Leão, Oscar Nimeyer…

Read more

But the precarious state of Brazilian cinema also relates to the authorities’ distant or even indifferent attitude. The period covered by our programme was preceded – from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s – by a “dry earth” policy for the film industry. It was not until the Audiovisual Law enacted by Itamar Franco’s government and implemented under Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s presidency (1995) that film production was able regain its breath and its ambitions. In 1998, the international acclaim of Walter Salles’ Central do Brasil epitomised the success of this recovery plan, making this filmmaker into the most diplomatic ambassador for Brazilian cinema. Four years later, the still greater triumph of Fernando Meirelles’ controversial film, City of God (2002), meant that the national film industry received more sustained attention.

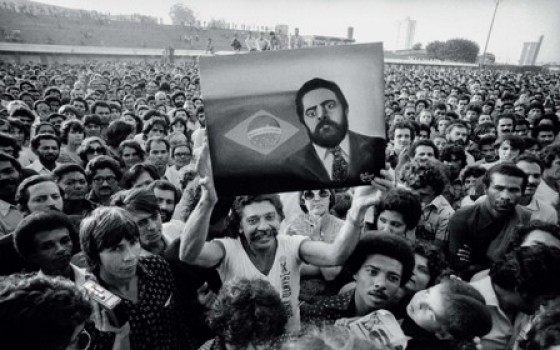

Our programme begins at this very moment, on the eve of Ignacio Lula da Silva’s fourth and victorious attempt to gain the presidency. Peões, a documentary from the masterful Eduardo Coutinho, recounts the militants’ saga through the words and memories of the humblest of his comrades in arms. By giving voice to the aspirations of a people on the day before the investiture of one of their own, this film seemed to us to raise the challenge of what means need to be invented to size up, in both a concrete and imaginary terms, a country about to play a major role on the international stage. From this standpoint, there is a remarkable correlation between the vitality shown by young Brazilian filmmakers and the government’s determination to stimulate the economy and reduce social inequality. From this starting point, we designed our programme as a map (which is the main motif of Karim Aïnouz and Marcelo Gomes‘ Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque te Amo) on which each film adds its grist to a concrete inventory of Brazil’s aesthetic initiatives and structural realities. Sopro (competing) and Because we Were Born by Andréa Santana and Jean-Pierre Duret (Paths that cross) will also be present, following on other films recently shown in Nantes: last year, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s O som ao redor (Neighbouring Sounds) and, in 2011, Girimunho by Clarissa Campolina and Helvécio Marins Jr.

The quite unplanned balance between documentaries and features – often bordering on the essay genre – also enriches this inventory, which closely reflects the countless disparities in Brazil and, above all, its filmmakers’ passion for the threads that weave together our vast world. The title of the collective film Desassossego – filme das maravilhas (Neverquiet – Film of Wonders) could be extended to cover the whole of the journey that we invite you to take, as for us it encapsulates an excellent proof.

Jérôme Baron