Sparkles of melodrama

Melodrama is just one of myriad film genres, but it appears to have dominated the compass of popular cinema for a very long time. More precisely – and without forgetting slapstick – it should be seen as the laboratory and wellspring of the cinematic formulas that served as touchstones for audiences and the film industry and then went on to impregnate other forms of film entertainment to different degrees: historical films, westerns, comedies, crime films…

Although perceived as short on action, melodrama still managed to anchor its formulas – family dramas, tormented impulses and thwarted love, improbable twists of fate, often disappointed quests, the hold of social convention on individual choices, class dissension – on the side of spectacle, or in other words of sensation. Enjoying mass appeal, the ‘poor man’s tragedy’ draws contempt or even sniggers from those either too educated or too partial to be able to see anything else in it. It is not always possible to refute the long-standing reproach levelled at cinema – that it boils the world down into formulas that are simplistic, quickly digested and carried over from one film to another. Industrial and commercial strategies lay down the law of series and, if the narratives repeat themselves, this is also to highlight the shades of difference more effectively. Each variation, each deviation, twist or detour can be spotted by the audience and is likely to make them a sign before making sense.

The famous quote, “cinema substitutes for our look a world which conforms to our desires”,1 implies that by offering the audience things known, or more exactly things recognisable in an ideal and codified mode, cinema’s first triumph is its extraordinary ability to make the tumult of the world more decipherable, more understandable. What melodrama reveals through its excesses – the violent swings of events, the contradictory turmoil gripping the characters, the exacerbated emotions, the hysterical music and palettes of colour – is the genre’s modus operandi. The genre is made visible as it formally objectifies the irrational unleashing of forces (social, ideological) that determine destinies and marshal human desires. Film after film, audiences worldwide, be they American, Mexican, Japanese or Chinese, are initiated into the virtues of melodrama. The first of these is the confirmation that we are all subject to a social order that places individuals in a potentially contradictory or conflicting relationship with their environment. The best melodrama thus embodies the register of popular culture whereby the (con)quest of what is close and ordinary – in other words, the forms of social life – is based on an exemplary and illuminating model in which entertainment is both the apparel and the necessary condition.

Although the mould of convention and expectations has gradually regulated the genre’s best practices, some filmmakers have cultivated a healthy temptation to transcend these. What they propose has the essential quality of occupying and deepening melodrama’s moral space. As they put more personal visions (and thinking) into their films, their purpose can adjust to evolving contexts. And, although melodrama’s appetite for bygone times is gradually waning, it still calls on them occasionally to touch the social body in an oblique manner. In fact, the popularity of melodrama results above all from its firm cultural anchorage and its dramatized observation of how changes affect the equilibria of dominant social and ideological norms. On both sides of the screen, melodrama is first and foremost about the people we are. The films gauge the balance of power between dominant polarities (e.g. masculine identity, definition of the feminine gender, filial subordination under patriarchy, the characters’ solitude and frustrations…). They find some sort of space for expression – liberating at times – in which the testing of the characters’ desires reveals invisible (or repressed) areas of our moral universe. This revelation is basically about exteriorising emotions, which in itself creates the image that the audience expects of an intelligible representation of our inner states. On-screen emotion… visible, recognised and shared.

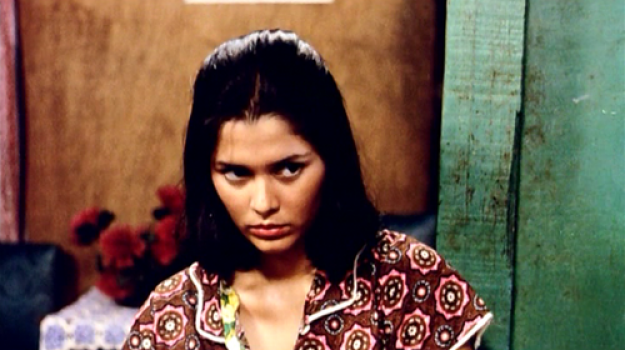

In Griffith’s wake, Western melodrama offers many examples of the genre made to perfection: King Vidor, Vincente Minnelli, Douglas Sirk, Leo McCarey – who does more than draw tears of laughter – Max Öphuls – who managed to convince everyone around him, from Berlin to Hollywood – the art of the stappalacrime of Raffaello Mattarazzo in Italy, Jacques Demy in France, Rainer Werner Fassbinder in Germany, or closer and certainly more randomly some of Pedro Almodovar’s films, to name but a few. Moreover, melodrama’s narratives and forms abound in cinema worldwide and call to mind some equally outstanding successes that confirm the universality of the genre. Here, our ambition is not to retrace the history of these films that are so essential and precious for our understanding of cinema. We are attempting more modestly to reinstate emotion into the art of cinephilia. The programme is rather an invitation to a close-up look at some of the gestures that will continue to make a sign to us, in the landscape of great popular art, for a long time to come. Alongside Kenji Mizoguchi, Emilio Fernández, Mikio Naruse, Stanley Kwan, Lino Brocka, Xie Jin or Li Hang-siang, let’s wager that melodrama’s determination to unabatedly draw the vagaries of the heart and soul towards intelligence and beauty will help each of us to clarify what we expect to find in our encounter with a film. Could it be that our expectancy lies in that mysteriously troubling moment when we no longer have to choose between the deep dazzling reality of appearances constructed by the film, and the life we live without forgetting to dream it? The infancy of the art, a magnificent secret, a sparkling enigma, the insatiable search for emotions that we long to rediscover with the greediness of a bounty hunter. The sublime paradox of tears!

Jérôme Baron

1 In the opening credits of Le Mépris (1963), Jean-Luc Godard reads out this apocryphal sentence, which he wrongly attributes to the critic, André Bazin. One that, to all extents, is an enriching point for reflection.