Over the last few years, it will not have escaped the attentive eye that Colombian cinema has been marked by its assiduity. Regular selections in major film festivals, more frequent screenings abroad, a raft of unknown names that will hopefully grow longer and some names that are becoming more familiar: Oscar Ruiz Navia, Rubén Mendoza, Juan Andrés Arango… and more specially for our Nantes audiences, Nicolas Rincon Gille, who directed Los Abrazos del rio, the first Colombian film to be awarded the Montgolfière d’or. Benefiting from a comprehensive support scheme for the film industry, introduced in 2003 after a ten-year funding vacuum, Colombian cinema now seems to be in a position to envisage future horizons. Local film production is now on the upswing, certainly in terms of numbers, but also very much in terms of quality. On this count, it now seems to be keeping abreast with developments in other Latin-American countries like Argentina, Mexico and more recently Chile, who have so far been the front-runners. The Colombian cinema’s new vitality has been accompanied by what we feel are changing and uncompromising viewpoints on national realities and the developments that some economists have dubbed “Colombia’s economic miracle”. This burgeoning cinema is today asserting its determination to abolish, or at least cross, some internal frontiers. More often than not, the films seem to stay clear of urban spaces as if driven by the desire for closer ties with the extraordinary human, cultural and geographic wealth of a country wedged between the Andes and Amazonia and bordered by Pacific and Caribbean coastlines. Rather than playing on exoticism, the young Colombian cinema is fiercely determined to go beyond the country’s image of chaos and violence and do away with past divides (political, regional, moral, racial) by integrating the imaginary dimensions of its multiple identities. An approach that enables cinema to be in step with its times and to envision this ontologically diverse Colombia as an inspiring prospect (La Playa D.C., La Barra, Los Hongos). This sustained, receptive attention to what makes (has made) the country is helping to drive and reflect the transformation of Colombia’s social awareness during a period of major change. In parallel, we also wanted to ask ourselves whether this contemporary cinema fitted into some kind of genealogy. Whether there were some precursory signs in the bumpy and little-known history of Colombian cinema that we might be tempted to identify, revisit and compare with its current ambitions and projects. Gathering together short and feature-length films, fiction and documentary, the thirty-three films in the programme represent the broadest panorama of Colombian cinema ever screened abroad.

Filmmaking in Colombia has always been a challenge for those who have tried and the history of Colombian cinema is irregular, advancing in fits and starts, marked by a discontinuity that puts to the test any temptation to arrange it into a coherent narrative. One example epitomising the historic opportunities that Colombian cinema has missed is its protracted period of silence that ironically begins in 1928, the year that the world began its gradual shift towards talking films. From then until 1940, a full twelve years later, no Colombian feature film was made in the country. And thereafter, when some initiatives had emerged and the State (in 1942) had framed a law to support and firm up the national film industry, the country had neither the necessary private financing, nor the technical skills or infrastructure to effectively make a fresh start. As a result, the domination of North American cinema was contested only by Mexican and Argentine production, which were then both entering their first golden age. In 1948, after nearly half a century of relative calm, Colombia plunged into a bloody civil war known as “La Violencia”, which left more than 300,000 dead (2% of the population). This traumatic episode in Colombian history is key to understanding its recent history as it is at the root of today’s internal conflicts. Julio Luzardo’s El río de las tumbas (1965), that surprisingly echoes down as far as Dunav Kuzmanich’s Los Abrazos del río, Canaguaro (1981) and Francisco Norden’s Cóndores no entierran todos los días (1984) – the first Colombian film screened at Cannes – revisit this dramatic period in different ways. In a highly unstable context, how can cinema find more suitable ground to develop? Our programme returns to two films of the time, as they illustrate two very different paths and inclinations of cinema during those years. The first film, made in 1954, is a collective work of surrealist inspiration and now constitutes a precious historical document. It was co-directed by Luis Vicens, who that same year founded the Filmoteca Colombiana, the journalist and author Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, Enrique Grau Araújo, a leading figure of 20th-century Colombian painting, and Gabriel García Márquez who then regularly wrote film reviews for the newspaper El Espectador, and reveals the keen interest that cinema held for the country’s left-wing intellectual elite. They were, one supposes, extremely frustrated by the situation. On the other path, El Milagro de Sal made by the Mexican Luis Moya Sarmiento, who was hired by the Antioquian producer and advertiser Antonio Ordóñez Ceballos, underlines the determination to integrate the powerful motifs of Colombian reality into a cinema intended for the general public.

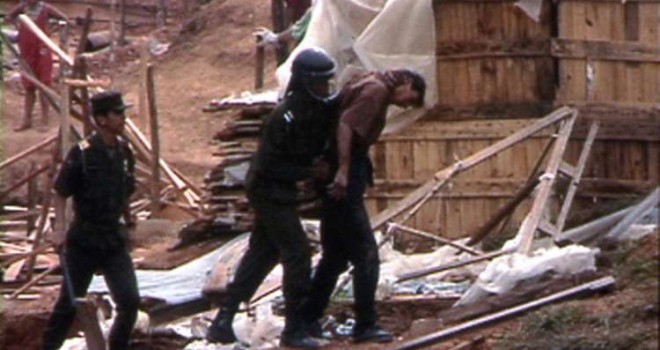

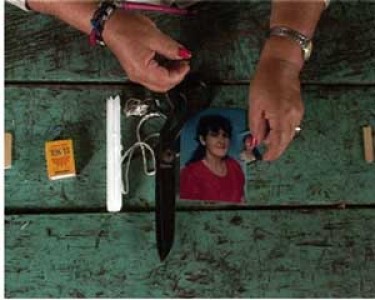

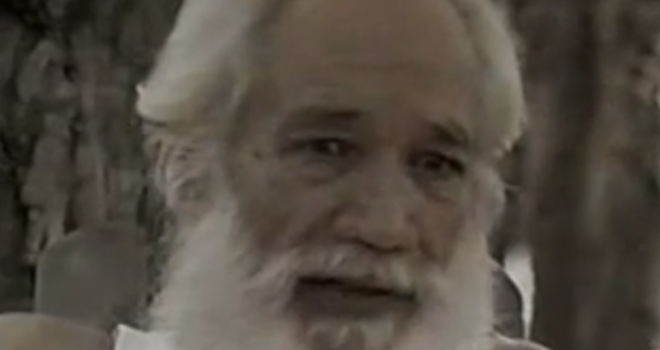

Inextricably and perniciously linked, the civil and military, urban and guerrilla violence, and then in the early 1980s the drug-trafficking and social unrest caused by persistent and deep-rooted inequality, reinforced the country’s negative image. Cinema, like the people it was intended for, seemed held to ransom by the persistence of a highly entangled situation. Yet, in the late 1960s, when an anti-authoritarian and libertarian spirit was sweeping across a large swathe of South America in very diverse forms, in Colombia, other cinematic visions were taking shape – more homemade, less industrial and strongly influenced by a documentary approach. Here, we outline the two main polarities. First, a group of four influential contemporaries – Carlos Mayolo, Luis Ospina, Ramiro Arbeláez and the meteoric genius Andrès Caicedo (who died aged 25 and is seen as one of the most influential figures in Colombian literature) – established Cali as the country’s cinematographic hub. Impassioned film-clubbers and editors for the film review Ojo al Cine (1974–1977), they made a series of documentaries that placed a strong and innovative focus on social realities, thus continuing the line already present in Caicedo’s writings. Carlos Mayolo (1945–2007) and Luis Ospina, who partnered up on various projects and also made films separately, channelled Colombian cinema into registers that criss-crossed experimental, documentary, fantastic and archival films. The second pole comprised the duo Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva, who developed original documentary films that were unprecedented in the Columbian context. Based on sound theoretical thinking in ethnography and sociology, their films (here Chircales, Planas: testimonio de un etnocidio, Campesinos) never separate a vision of the present from the reflex of calling on historical memory.

Certainly, the Cali school and direct cinema as revisited by the Rodríguez and Silva duo provided effective anchors and important landmarks for today’s generation of filmmakers. Even more crucially, these films – whose qualities can be seen in terms of an interesting complementarity – are among the rare films to have stood the test of time and, by their very existence, made a history of cinema seem feasible. Marta Rodríguez, like Luis Ospina, is still being screened forty years on.

At the limits of the contemporary period, the emblematic films of Victor Gaviria (Rodrigo D. no Futuro and La Vendedora de Rosas) and La Boda del Acordeonista by Luís Fernando “Pacho” Bottía are among the films that benefited from the first government policy to effectively support the film industry. On its inception, FOCINE (Compañía de Fomento Cinematográfico) was mandated to administer a state fund dedicated exclusively to the film industry. Between 1976 and 1993, this initiative, which was closed down because of proven corruption, enabled the production of some thirty feature-length films and even more shorts. It can certainly be considered as a determining factor and necessary prelude to the new 2003 initiative. This formal institutional commitment has, above all, lastingly integrated the situation of Colombian cinema into the political debate and highlighted the fact that it has an artistic, cultural, educational and traditional heritage role to play in a country where discourses now seem decisively turned to the future.

Garras do Oro (1926) by P. P. Jambrina (a pseudonym) is the earliest film in this panorama and recounts the history of Panama’s separation from Colombia (1903) – an amputation that the film turns into an anti-imperialist accusation against the United States. One century later, Colombian cinema, providing that it does not give in too quickly to the arty and conformist trends of world cinema, seems to be showing enough verve to make it one of the best ambassadors of the country’s intellectual and artistic life.