Although the exceptional vitality of Hong Kong cinema is currently losing steam now that the industry is having to adapt to the commercial (and political) realities of the new China, it is the result of a history that saw generations of Chinese migrants converge on the region in successive waves. Over the last half-century, the Hong Kong genius for concentration has thus gained from the valuable clustering of skills and inspirations (actors and actresses, singers, scriptwriters, set designers, martial arts experts and choreographers, directors and screenwriters, entrepreneurs and producers) that have enriched a film production accommodating two languages. Take the well-known example of the Shaw Brothers and its emergence at the end of the 1950s. The studio set up in Hong Kong at a time when Mao Zedong was beginning to reshape China’s film production Ingeniously transforming the WB of Warner Bros into SB, the Shaw Brothers acquired an efficient studio that produced films exclusively in Mandarin Chinese for the large and educated diaspora from Beijing and Shanghai (and elsewhere) living in Hong Kong. Reputed and appreciated for its gangster films and melodramas, the SB promoted a nascent genre, wu xia pan (swordplay film), and ambitious costume dramas such as Li Han-Hsiang’s masterpieces (e.g. The Kingdom and the Beauty, 1958). The Shaws innovated by returning to traditional Chinese stories, opera and the martial arts at a moment when the composition of audiences was changing. We see here that, while the main role of Hong Kong cinema is entertainment, it often has a keen and singular grasp of the overall picture enabling it to adapt to changing audiences and to create new references for them. Among the classic swordplay films, The One-armed Swordsman (1966) opens Chang Cheh’s one-armed swordsman trilogy (Tsui Hark’s The Blade is a remake of part three, The One-armed Swordsman) and stands out from the first masterpieces of King Hu (e.g. Golden Swallow, 1966) for its use of a more abrupt choreographed violence that intensifies as the trilogy advances. Although Hong Kong cinema first gained some recognition in the 1960s partly thanks to the valuable contribution of the three aforementioned directors, it was not until the 1970s with the arrival of Bruce Lee as such (he had already had many small roles in numerous films and television productions including The Green Hornet) that the aura of this world-famous kung-fu film star brought Hong Kong cinema recognition in the eyes of audiences all over the world.

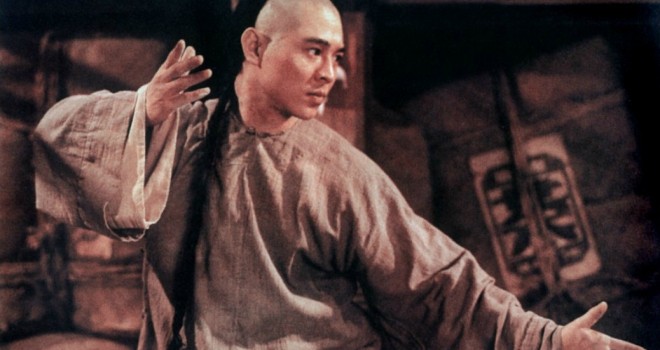

At the tail end of the 1960s, the Cultural Revolution in turn drove many – this time Cantonese – to seek refuge in Hong Kong. At the same time, Raymond Chow left the SB. He leased a film studio from Cathay, the other large company present on the territory, and founded the Golden Harvest studio, which was to become one of Hong Kong’s majors. The idea of making modern Cantonese-language films coincided with the ambition of Bruce Lee (San Francisco-born but shuttling between the US and Hong Kong) to make a name for himself on screen. After several failed attempts to convince the SB, he was hired by Raymond Chow – a risky move given that the actor was still suffering the after-effects of a serious accident that had happened during a workout one year earlier. Big Boss (1971) was shot in Thailand to reduce production costs since the actor’s fees were high. But the phenomenon was launched and his success was as immediate as huge. However, Bruce Lee’s entry into Hong Kong cinema destabilised reference points and hierarchies. In the space of three years he became an unrivalled icon, a myth that was finally sealed by his premature death. Film after film – Fist of Fury (1972) is a second example – Bruce Lee imposes a unique on-screen presence, an unprecedented physical explosiveness that ejects all his opponents out of the frame. Blows hail down, concise, fast, some say unrestrained and even political (his opponents are often Japanese occupiers, Western rivals, unscrupulous mobsters), driven by a thirst for revenge that Lee liberates with an unparalleled concern for performance. In terms of mise en scène, Bruce Lee’s speeds called for an adapted response. The movements needed to be visible in their entirety, which required wide-angle or medium shots. However inimitable he may be, kung-fu cinema, and more generally action cinema still bear the lasting imprint of his presence. But the question then arose of how to continue tapping into this gold vein that stretched across the world and how the vacuum left by the inimitable Bruce Lee could be filled? By making him into a film character, as in the ineffable Bruce Lee against Superman (1975)? Or by making sequels to the films he had starred in, such as The New Fist of Fury (1976) by the same Lo Wei… The example of Bruce Lee had the merit of spurring ambitions to create exceptional role models, and new projects soon appeared, such as the films directed by Liu Chia-Liang (former stuntman and choreographer for Chang Cheh at the Shaw Brothers, famous for the The 36th Chamber of Shaolin trilogy – begun in 1978). But it is with Jackie Chan that Hong Kong cinema found its new champion, who incidentally was one of The Seven Little Fortunes (a troupe of child martial arts performers aged from 7 to 14) and through them had ties with a key generation in Hong Kong cinema (co-starring with them in many films) including Sammo Hung, Corey Yuen, Yuen Biao… Although Jackie Chan took over from Bruce Lee in Lo Wei’s earlier-mentioned sequel, he quickly distanced himself from this vampire-like shadow. He even brilliantly stymied Bruce Lee’s all powerfulness by adopting completely opposite traits: turbulence, disrespect, clumsiness, slapstick, cowardice, acrobatics, humour, parody-like self-derision, duration and rebounds as opposed to speed and concision. His collaboration with the brilliant choreographer and director Yuen Woo-Ping (who staged the fights in Tigre et Dragon, Matrix and the Kill Bill films) soon brought him success. Drunken Master (1978), which also led to sequels, is a remarkable illustration of the freedom of tone and acting that their complicity allowed. Kung-fu and comedy go hand in hand in most of Jackie Chan’s films, opening the way to a broader-based and intergenerational audience. Hollywood was already showing an interest in the actor, who had moved into directing with Police Story (1985, starring the beginner, Maggie Cheung). Stuntman, actor, director and soon producer, Jackie Chan gained a popularity that has made him the new icon of Hong Kong cinema. He has become a trademark, a power that he successfully manages thanks to his progressively widening functions.

Between innovation and a constant rereading of tradition, the Hong Kong cinema of the 1980s and 1990s extended its influence even further afield and entered a truly golden age. Tsui Hark’s swordplay films integrate Hollywood’s newest technologies (particularly in Zu, Warriors from the Magic Mountains – 1983), while John Woo, produced by Hark, dissolves the frontiers between genres (film noir, war film) and has them converge into pure action, so much so that action becomes invested with meaning: acting, already implies thinking. This approach was underpinned by a powerful idea and a sometimes tragic vision of its times. Deliberately intuitive and adventurous associations where cinema relies on secret recipes, these and other examples served as inspiration even for the prototypes regularly released by the To-Wai Ka Fai duo from the second half of the 1990s, when a generation of Hong Kong filmmakers worried by the retrocession chose the exit offered by Hollywood.

Long Arm of the Law (1984) – directed by Johnny Mak, produced by Sammo Hung and followed by two sequels – radicalised what was to become one of the most exciting energies of Hong Kong action cinema by shooting at real locations in the city. And during those years, Hong Kong became one of the most fascinating studio-sets of contemporary cinema, emblemised by the famous district of Kowloon Walled City, demolished a few years later. This deep-rooted relationship between a city and its cinema has remained quintessential right through to the auteur films, including of course those by Wong Kar-Wai. The tonalities vary, as do the ambitions, but it was above all during those years that popular Hong Kong cinema affirmed frontally and sometimes brusquely that the genre film was able to take an interest in and reflect on the realities of its time. John Woo thus transports the infernal trio of Bullet in the Head (1990) from the Walled City into the hell of the Vietnam War. The amusements of petty crime and street bravado give way to the extreme situations of war. But the Vietnamese context soon reveals the obvious allusion to the more recent Tiananmen events, conveyed in the film through the idea of a youth sacrificed under a hail of blows and bullets.

Produced by Tsui Hark but directed by Ching Siu-Tung, the first part of A Chinese Ghost Story, which is a remake of The Enchanting Shadow (1960), revisits the swordplay film and sustains its fantasy dimension with a surprising erotic tone (a nod to Li Han-Hsiang?), giving an overall coherence to the plasticity of a film where desire and fear fit well together. This gives the film, where innuendos about the terrifying spread of HIV abound, a poetic clarity rarely attained by the genre.

The six films that we are presenting this year are notable in themselves. But when we look at Hong Kong cinema – and here we have mentioned just a few films among many – the microcosm that spawned it induces a whole web of connections between the films, the countless remakes and sequels being just the tip of the iceberg. Indeed it was perhaps Hong Kong that prompted Hollywood’s sequel mania that was so popular in the 1980s? The existence of an ascendance or lineage between the films anchors Hong Kong production in a history. Its links are never totally anecdotal or the simple product of an industrialized output. Added to the artistic worth of many works, this dimension of Hong Kong cinema stimulated the curiosity of a whole generation of French cinephiles. The informed welcome they gave to these films once again showed that entertainment and knowledge are valuable, especially when they are inseparably coupled.

Jérôme Baron