Programmation : Jérôme Baron (Festival des 3 Continents), Catherine Hass, Anne Kerlan & José Quental (IHTP/ CNRS)

Tricontinentale : In the present

Between the Tricontinental Conference held in Havana 50 years ago in January 2016 and the 3 Continents: just a question of resonance? Not only. When the festival opened in 1979, the term “Third World” sparked some reticence with respect to its miserabilist and derogatory connotations that the founders fittingly wished to avoid. Yet the fact was that films from Africa, South America and Asian countries came in the main from this so-called “Third World”, which was still off-camera for the most part, leading to both an absence and disavowal of its multitudes and singularities. There were indeed two, perhaps three, worlds – far-removed for many people. So the 3 Continents Festival then took up the ambition of showing films or rather enabling them and their makers to reach us. These numerous and important discoveries had the effect of nibbling away, and sometimes biting, at our prevailing hierarchies. The emerging films exhibited a broad range of forms and highly varied contexts in the wake of the newly won independences. What was visible were not only talents, but also the aspiration to forge distinctive as well as personal forms of filmmaking in the here and now. The work of catching-up was intense and relayed by other events: on the one hand, unknown treasures of the past were exhumed while the other hand was taking the pulse of contemporary creation. Yet, after a troubled decade during which cinema had also been “novo” revolutionary, activist, utopian and political for better or worse, the need appeared, more clearly than ever before, to confront the old orders and present arrogance that sometimes reigned with the same old authoritarian violence. Here or there, it was indeed tempting to believe that cinema had – more than its word to say – a precious role to play in the ideas and societies where it was present. Here or there, it also happened that cinema’s arrangements with politics (and the notion of culture) officialised its entry into the serried ranks of servility. In those countries not at war, many regimes were already firmly in place at the beginning of the 1980s.

Over the past thirty or so years, the map of the world has changed, not because the inequality gap between the rich and poor countries has closed or because the North-South divide has been overcome, as evidenced daily. Indeed, in the poorly orchestrated concert of globalisation now amplified by a torrential technological revolution, change has come about with the emergence of new economic and political powers and the rise of new hubs and trading practices where money nonetheless remains the end and not the means. The basic problems of swathes of humanity are still not resolved. On our three continents, which are younger than in the past owing to demographic trends, the disparities, asynchrony, convulsions and discontentment, of which we are both actors and powerless witnesses, persist and become even more complex. It is not so much that there are two or three worlds, but rather an environment with many interlocking levels of dependence, meaning that each eddy propagates a shock wave with geopolitical and macroeconomic consequences that are too unpredictable to be forestalled.

Notes

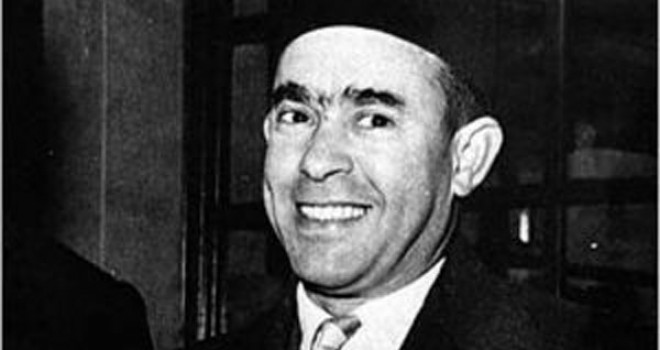

When Mehdi Ben Barka called for the Tricontinental Conference (which took place without him and thus had limited impact), he had in mind a completely different idea of progress from the one that already governed the world. He believed that liberated peoples, who for some were again oppressed (as in the case of his own country, Morocco, whose independence had been hijacked by the monarchy), always have grounds for rebellion. The world’s leading (imperialist) power had been engaged for a year – or ten depending on how one views the American involvement in Vietnam – in a war against this small Southeast Asian country only just liberated from a century of French occupation. The case of Vietnamese attracted and crystallised attention as shown by Che Guevara’s now famous message to the Tricontinental: “How close and bright would the future appear if two, three, many Vietnams flowered on the face of the globe, with their quota of death and their immense tragedies, with their daily heroism, with their repeated blows against imperialism, forcing it to disperse its forces under the lash of the growing hatred of the peoples of the world!” Ben Barka’s intentions were less spectacular, more strategic. Yet, the two men, both exiled, enjoyed a growing complicity during their 1964 contacts with the rapidly ousted young Algerian president, Ahmed Ben Bella, and shared converging analyses of the situations around them. As Vice-president of the AAPSO (The Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization) created in Cairo, 1 January 1958), Medhi Ben Barka also administered the solidarity fund. The prime objective of the Tricontinental was to broaden AAPSO’s base by integrating the Latin American and Caribbean countries. A bureau of six Africans, six Asians and six Latin Americans set about organising the conference, which Cuba had offered to host in Havana. The Moroccan leader, now pan-African and Third Worldist, was to be president but, at the end of October, he was kidnapped in Paris and then assassinated. In addition to expanding into a tricontinental organisation, the conference set several objectives including the rallying of all independence movements (originally the watchword of the Bandung Conference that was masterminded by the Chinese and Soviet Communist Parties), the building of solidarity mechanisms among Third World countries, the organising of a world revolution, the fight against segregation (mainly South Africa’s apartheid system), a movement against the use of nuclear technology, imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism and neo-liberalism.

No attempt will be made here or within the current context to verify the relevance of either the premises foreseen for the implementation of this revolutionary programme or the utopias envisaged. But let us for once agree to give the term a positive ring. On the other hand, jpwever, it will not be hard to show that this agenda now resonates with a concrete state of affairs. What does this mean? That there does seem to be what the historian Jean-Noël Jeanneney chooses to call “Une concordance des temps” (concordance of tenses or times)? Or rather that we would be wrong to consider the struggles and issues of those days as bygone stakes? It seems, in fact, that although they were formulated in specific circumstances, they still constitute challenges to be overcome in today’s societies, which are more cosmopolitan than ever. And were we to see the return of different kinds of obscurantism and fundamentalism, be they religious or neo-fascist of the worst kind, it is partly because these have never been resolved by the mercantile nations that are expanding their control over corrupt terrains – tolerant and deregulated – and politicians who have lost control of the balances of power or compete among themselves alone.

Revisiting, among the host of other possible films, the fourteen in this programme (the first intuitive list included nearly forty) doubtless means picking up the thread of a history that is as much past as imminent. It means being moved by the films in space and time but also challenging the comfort of a few certainties and getting back down to work – let’s not forget that there is enjoyment to be had in this. At least, it may put a little clarity into some of our ideas?

Our programme is one that nourishes no nostalgia for what has not happened (bar the now marginal tie between cinema and politics), but one that is anxious (how else could it be?) about what is brutally being allowed to happen. On the endless horizon of cries, revolts and dramas that flit by daily in silence without our ever really facing them, the cinema retains perhaps the ability to establish an aesthetic relationship with its spectators. Going beyond the mirror that helps us recognise the world, these visions help us to take the time to let them journey within us. We hope that they will be beneficial to the point of dissipating somewhat this crime of opinion that besieges us.

Seen from here, this is at least what we continue to believe…

Jérôme Baron