For the cinephile, the work of Im Kwon-taek (born in 1936) remains a paradox. The filmmaker’s aura places him among the foremost South Korean directors but, at the same time, he is one of the least known giants in the history of cinema. Out of his prolific filmography – which now counts one hundred and three feature films, including fifty made between 1962 and 1972 – how many have we seen? How many have been released in our country? He has not been the privilege or preserve of a small group of experts, as we would likely have noticed some French publications on his work, but these are sorely lacking. So far, only one study (by Lee Soojin) on the film Chunyang (Chunhyangdyeon, 2000) is available, along with a few articles in specialist journals. But recognition of Korea’s cinematographic brilliance was late in coming, growing gradually from the 1990s onwards, and Im Kwon-taek is no exception. Although some retrospectives had laid a few waymarks, as in Nantes in 1983 and 1989 (an early tribute to Im Kwon-taek) then at the Paris-based Korean Cultural Center and Cinémathèque française, our knowledge on him is indeed wanting.

The longevity and scope of Im Kwon-taek’s work invites us to look back, albeit briefly, at the itinerary that has shaped it. For over ten years, the filmmaker learnt his trade on the job, making as many as twenty-two films in three years (1969–1971) including eight in his most prolific year, 1970! He is a studio craftsman and the last active witness of a bygone age in cinema history. Practice is what gave him his craftsmanship but he soon ran out of steam and began asking himself questions: “It was a hard time for me. People did not come to see my movies, and I myself was losing interest in them as well. Whenever I received offers to direct, I just woke up the next morning and went to work as part of a routine, only to make a living. I thought my life would just end like that. And it got worse everyday.”1 He had just completed his 49th and 50th films. The year is 1970, on the eve (1971) of Park Chung-hee’s re-election to the presidency of the Republic of South Korea. On 6 December that same year, the president decreed the state of emergency and the film industry, like the whole country, was forced to follow the path of modernisation imposed by the dictatorship. Audiences drawn by the appeal of television were deserting the film theatres, and cinema was catapulted into a period of crisis. Im Kwon-taek: “Looking back, I felt like I was living my life telling truly dishonest lies. So I decided that I had to find some way to put more meaning into my life. That was how it started. It was nothing grandiose. I just thought if I dealt with something that touches my heart, to show the sort of ordeals that we all experience, and to lie a bit less, I would probably be able to change the pattern of filmmaking I had followed until then.”2

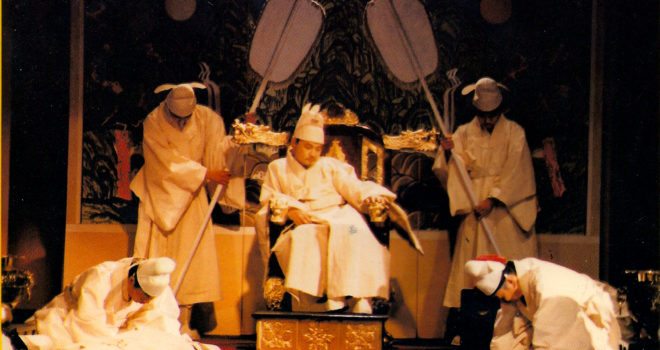

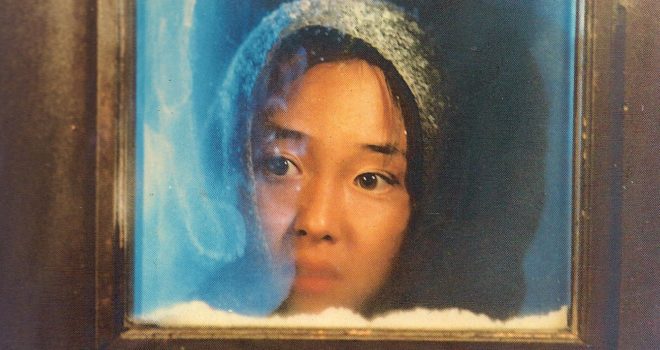

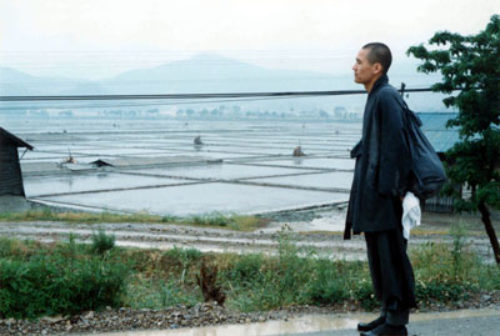

Whilst these years seemed to bring to heel some leading Korean directors such as Lee Man-hee and Kim Ki-young, they signalled a turning point for Im Kwon-taek. Yet, the pace of his filmmaking slowed down only moderately, with twenty-six new films made between 1972 and 1979. Weeds (Jabcho, 1972), a film he produced and directed and the only one to disappear without a trace except for a few photogrammes, is often seen as marking the filmmaker’s change of direction. At the time, he was ignored by audiences and critics alike. Given the scarcity of material, it is hard to form an objective idea of what film represents for the filmmaker. The context of his “programmatic” change of course is not as simple as one might think and his subsequent films continue to disconcert and intrigue us, alternating personal creations (but which are these exactly?) with more commercial films in which Im Kwon-taek continues to observe his country’s present and still recent history. Of the films we are screening, we could for example unhesitatingly place in the first category Genealogy (Chopko, 1978), Mismatched Nose (Jjagko, 1980), Divine Bow (Singung, 1979) and Mandala (1981)… In the second, possibly Does the Nakdong River Flow (Nagdonggang, 1976), Seize the Precious Sword (Samgugdaehyeob, 1972), and the more recent The General’s Son (Janggun-ui adeul, 1990) and its sequels. But where does the remarkable Wangsimni, My Hometown (Wang Sib-ri, 1976) fit in? This diversity, rather than confuse us, should raise questions about the identity and vocation of his work. In his searching, Im Kwon-taek never abandons the desire to win over audiences to his films and he never rules out one film form to the benefit of another. The genre cinema coexists with initiatory and spiritual experiences, portraits of women… This rich, seemingly divergent and dissimilar continuity is doubtless one of the most atypical features of his work. For what is implicitly present – and which requires no erudite reading – is the pleasure that Im Kwon-taek takes in focusing on the characters and the stories they inhabit rather than formally demarcating the traits of an art that distinguishes an author. So with students, small-time gang leaders, blind pansori singers, villagers from isolated regions or a fishing community and disinherited city dwellers, Im Kwon-taek’s work anchors the history of South Korea and its people in the presents of cinema. He puts the past in contact with the present (Gilsotteum, 1985), the archaic with the modern (they rub up against each other remarkably in Village of Haze, Angemaeul, 1982), the town with the countryside, the Confucian tradition against the criminal underworld. Im Kwon-taek does not sublimate or dream his country, he recounts it. His work thus seems to find its continuity in the plurality of expressions that it reveals. And if we take a bold view, as his films incite us to do, there is a ready temptation to couple his work with the dramatically stifled history3 of a country whose growth and transformation have nonetheless been among the most dazzling of the latter half of the 20th century. Given this context, it is difficult not to lose sight (blindness is a recurrent motif of the films dealing with tradition) of what the still makes up the Korean people – perhaps a little miraculously. With no moralising aim or conclusion, all of Im Kwon-taek’s films in turn propose an examination of the national conscience, a series of changing viewpoints that question the country whose story he tells. This gives the resentment once expressed by Im Kwon-taek a point of appeasement, and even better a springboard. The filmmaking job that once burdened him has become the condition for an abundant and plural work with lasting resonances. His variety, an original lever for creation. Without reminiscing on John Ford and his America, we should now more clearly appreciate the scope of a work that has no comparable dimension in Asian cinema. Its scale involves views spanning an entire century. For South Korea, Im Kwon-taek’s films are assuredly an incomparable legacy, a real national treasure.

The retrospective, which opens in Nantes and will continue at the Cinémathèque française, thus seems like a salutary catch-up session. And, together, we hope that it will help, ambitiously and modestly, to clarify the paradoxical situation of a living monument. Thinking and writing about him could now provide critics with a major challenge.

Jérôme Baron

Notes

1 Fly High Run Far : The Making of Korean Master IM Kwon-taek ; Korean Film Archive, Busan International Film Festival and IM Kwon-taek Film Archive and Research Center of Dongseo University, p.11.

2 Fly High Run Far : The Making of Korean Master IM Kwon-taek ; Korean Film Archive, Busan International Film Festival and IM Kwon-taek Film Archive and Research Center of Dongseo University, p.12-13.

3 Some landmarks: the Japanese occupation began in 1910; the country was divided into two blocs following World War II; the Korean war opposed the two blocs from 1950 to 1953; then two successive long political reigns, first that of the autocrat Rhee Syngman from 1948 to 1960, then from 1963 that of the increasingly dictatorial Park Chung-hee, who was assassinated in 1979.