We would have certainly been hard-pressed to give it a face in advance, but the common thread of the eight competition films and their companions in the official selection’s special screenings nonetheless gradually became obvious to us. This was not so much because they seem to resemble each other – their exhilarating diversity points rather to strongly assertive creations – as because they exhibit the same appetite for stories and forms without ever “showcasing”, so to speak.

Some titles (however) give us a hint or even announce it: “once upon a time”, “wheel of fortune”, “new old play” or “great movement”, feathers and fairies… But looking at these films, we can joyfully say that it is well and truly there, firm and alive, that it is fictionalising and burgeoning, ready to welcome us, transporting us rather than grandstanding: no forcing, no clutter of references, no cumbersome tributes, no powerlessness to film hidden behind the trappings of fiction or a cinema that harks back to the past. Here we have filmmakers returning to their craft – filmmakers from the world over and in every way possible, be it erudite, absurd, subtle, shaman- istic, humble or mischievous – so that cinema can invent an echo chamber of reality, capture reality in the net of an immediate environment, as when Natesh Hegde films Pedro at home with his father in the leading role, in a place with all its residents, like the prison in Rancho, or from a film studio, albeit improvised and not devoid of a trace of ambiguity, like the apartment in The Inheritance.

Running through the competition films in particular are tales and opera, popular cinema, finely wrought narratives, be they incisively concise or of choral amplitude, a musical or visionary ambition – but all for the purpose of etching out a relationship to the world, to humanity, to individuals, to societies or the currents of history.

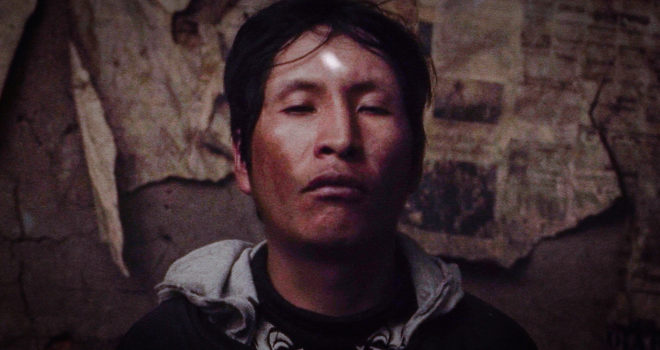

And this leads to some (more) surprises: such as the joyful romanticism and upfront political resilience of Vengeance Is Mine…, or the firm presence of the filmed world, paradoxically at tipping point, conveyed through a gesture that could have been in- stead entirely abstract (the disconcerting dimension of The Great Movement, which is pré- rather than post-apocalyptic and deploys feverish antennas rather than mimicking nothingness).

A young Indian filmmaker inscribes, like an painful, epic but intimate poem, a confused and troubled present surrounded by the living screens of old films projected onto sheets and walls (A Night of Knowing Nothing). Another, Philippine, returns to the gestures of editing and framing, intermingling the fiction and documentary of silent film, with no backward-looking references (Tug), a momentum, an elixir of youth or primal substance that does not leave us all alone in the world – spectators or onscreen characters.

Jérome Baron, Florence Maillard and Aisha Rahim