The destiny brimming with intrigues of the filmmaker and producer Shin Sang-ok him into the protagonist of a story that eludes an opus essential to the understanding of Korean cinema. If the “kidnapping” of Shin ordered in 1979 by the North Korean despot Kim Jong-il following that of the actress Choi Eun-hee is the most sensational and polemical episode of a turbulent trajectory, it tells us indirectly about the situation of a filmmaker whose fate and work are inseparable from that of his country, Korea. Spanning some fifty years (1952-2004), the career of the man nicknamed “the Emperor of Korean cinema” would be like a split- screen putting in parallel the films and life of the filmmaker as a testimony to the vicissitudes of a man grappling with the contradictions of his time, from the years of Japanese colonisation(1) to the dramatic and irreconcilable partition between the North and South republics in 1953. With a touch of audacity, we would even be tempted to postulate that wanting everything out of cinema, Shin did not have to choose between the two Koreas. He was the actor and director – accidental or intentional – of an unsolved Korean equation. The film of his life was its fictional and incomparable formula.

Born in 1926 under the Japanese occupation in the small port of Cheongjin in the far north of the Korean peninsula, Shin Sang-ok showed early signs of an artistic vocation encouraged by his teachers, including Kim Ki-rim, a pioneer of modern Korean poetry, and the already recognised Kim Ha-geon, a graduate from the Tokyo University of Arts. Shin was selected for a programme supported by the Japanese Governor General of Korea to study art during World War II at a school in Tokyo (1943-1945). He was aged nineteen when he returned and the situation had changed. In the chaos of a now Soviet occupied North, and US-occupied South, which characterised Korea between 1945 and 1950, Shin chose not to return his home province. Like many of his compatriots, he survived, earning a meagre living by drawing posters for the US military office and cinema distributors. In 1950, the fratricidal Korean War broke out under the nose of a United Nations powerless to stem the confrontation set the Korean arena in the middle of the Cold War between Moscow and Washington. It was in this context that Shin Sang-ok discretely pushed open the door of the film industry and trained for two years under Choi In-kyu (Hurrah for Freedom, 1946) going from the job of prop master to stills photographer and soon after film editor. In 1950, he made his first feature film The Evil Night (1952), now lost. He first thought of producing it in Japan but the situation was inauspicious to his project, and the filming begun in Seoul was forced to move to Busan when the bombing intensified. The film was finished and edited in very precarious conditions before being premiered there. During this period, Shin shared the lodging of a yangbuin (as the prostitutes who sold their charms to foreign clients were called). According to Shin Sang-ok, this experience provided precious inspiration for the film. We imagine that a few years later it also fed into A Flower in Hell (1958), one of the filmmaker’s previous major works. He then worked on The Evil Night finished as photographer and cameraman in the Korean Airforce before embarking post-war on four new films between 1954 and 1957. This series of anecdotes could well have presented no more than a factual interest. But taking a closer look, we can pinpoint these years as a decisive turning point in the affirmation of Shin Sang-ok’s vocation of filmmaker. Material insecurity, constant worries linked to the turmoil of the war (he lost both his parents during the evacuation from the North), cinema became a refuge and source of hope for Shin Sang-ok, first to survive the war and then to escape poverty. The year 1953 marked first and foremost the end of three years of devastation in the Korean peninsula and the halt of a war that cost three million lives, but the advent of peace was also the time when Shin Sang-ok met the young actress Choi Eun-hee on the stage of the Daegu theatre. She was to become his wife and muse, and destiny managed to never separate them against all odds.

Read more

Melodramas

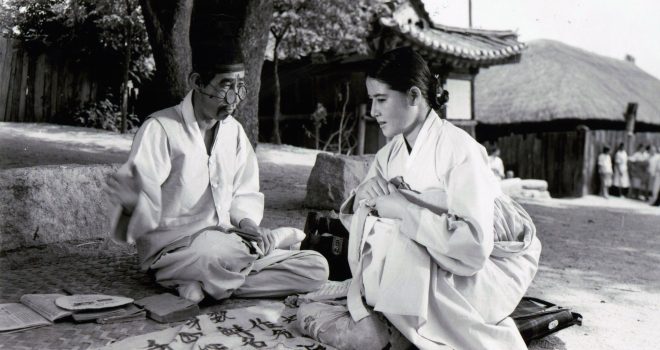

In 1958, the release of A College Woman’s Confession paved the way for the many future successes of Shin Sang-ok, who was keen to make a name for himself and gain experience by filming regularly. He thus made seven films in the space of two years for different productions before setting up his own company, Shin Films, in 1960 and establishing himself as producer-director with Romance Papa. The melodrama was a fashionable genre at the time and gave him the opportunity to garner large audiences particularly among women. Shin’s six consecutive melodramas, A College Woman’s Confession, A Flower in Hell, Dongsimcho, A Sister’s garden, It’s Not Her Sin, and Chun-hie (now lost), all gave a prominent role not only to female characters, but also and above all to his wife Choi Eun-hee, who in three years became an icon of Korean cinema. In everything they did, Shin and Choi worked to become an inseparable duo. The case of Dongsimcho (1959) illustrates this perfectly. The Korea Film Distribution Company had acquired the film rights to adapt a highly popular radio play and wanted to give the lead role to the young actress so as to ensure itself the best chance of producing a resounding success. But rather than contact her directly, the producer Park Woo-sam approached the filmmaker to arrange Choi’s hiring, finding it both obvious and advantageous that Shin direct the film. Yet, this story should not obscure the underlying reasons for its success. Abundant at the time, melodramas were blowing a Western wind over a Korean society in complete transformation, a genre that gave it another way of looking at itself. In front of Shin’s camera, Choi embodied all Korean women – the yangbuin, the war widow, the penniless student, the girl faithful to her father’s memory or, on the contrary, the young woman who defies paternal authority or is constrained by persistent Confucian values… Their success was due as much to the pragmatic intelligence with which Shin and Choi managed the opportunities that propelled their new status as stars and “modern” couple, as to the sustained proximity between the public and these little stories that, when stacked together, form a chronicle of their time. For Shin Sang- ok, the melodrama involved a gamut of tonalities meticulously revisited in each film, rather than being the sign of an author seeking to find through the genre his own recognisable style. So, in spite of his undeniable successes, the heterogeneity of his films in those years raises questions. While it points to a filmmaker fully engaged in his work, could we not also discern the contradictions of a man who is quickly adapting to the changes underway? Instability of family and social structures, the disappointing pursuit of a model for success, imbalances in gender relations: Shin Sang-ok seems to respond to the ongoing crises simply with a reminder of traditional morality, expressed in well- balanced combination of irresistible sensitivity and appeasing humour. The lucidity of his observation comes up against the threshold of the melodrama’s paradox: although appreciated by the public for its novelty, it most often remains a conservative genre.

Apolitical?

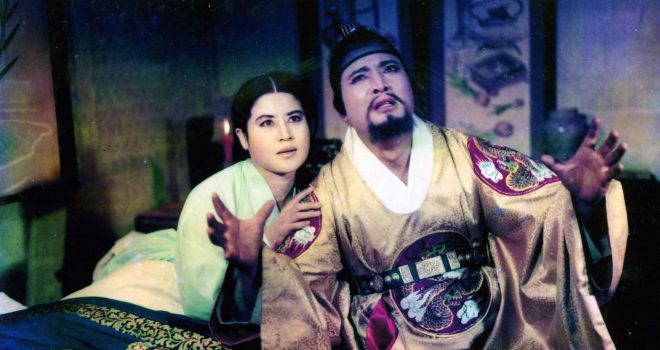

Although Shin Sang-ok’s films offer scant occasion for a political and critical reading of either the context or their intentions, the filmmaker’s trajectory on the other hand did not rule out a sometimes wily collusion with the powers that be. In 1959, Seoul’s strongman, Lee Seung-man, was seeking his third consecutive presidential term since he was first elected to lead the country in 1948. His popularity was declining and his close followers backed the project of making a sort of biopic to his glory. At the outset, Lee Byeong-il was to direct it, but one of the president’s bodyguards, who were keen spectators of Shin Sang-ok’s films, encouraged Lee to give the project to Shin. An incredible portent – Lee Seung- man and the Independence Movement (1959) was the first film to be made on the immense Anyang Lot. In the following years, Shin regularly filmed on the lot before eventually establishing there the ever- increasing activities of Shin Films, which made him the country’s most popular filmmaker and most influential producer from the mid-1960s on. Ten years later in 1967, he was able to purchase the same dilapidated Anyang Lot and finish building the largest film studio in Asia. The acquisition had been facilitated by Shin Sang-ok’s closeness – with no pledge of allegiance – to Park Sung-hee, whose 1961 military coup had ousted Lee (exiled) and gradually imposed an authoritarian military-industrial dictatorship in South Korea. During this period, Shin participated in drafting the new regulations desired by Park to frame and modernise the film industry. Ironically, the filmmaker himself found this legislation impracticable and detrimental to his activities. The first filmmaker to shoot in colour for the wide-screen (Seong Chun-yang, 1961), the first filmmaker to use optical zooms and long- range 250-mm zooms and to envisage synchronous sound for an entire film, Shin continually pushed back technical and financial limits (he worked with the highest budgets and no actress was paid more than Choi) and conceived his studio on the lines of a Hollywood mogul. His success aroused jealousies, further exacerbated by his arrogance, and he alienated a good number of his colleagues. Nothing seemed to resist him. Melodramas, historical and epic films, martial arts or fantastic films, Shin wanted everything from a cinema that built him up and absorbed him. In a little more than ten years, from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Shin Films produced over 200 films, opened the Anyang Academy of Cinema and Arts, a centre for training in cinema, and the Shin Film Acting Studio (in 1970), an acting school directed by Choi Eun-hee – until she was kidnapped. Although the filmmaker’s entente with the Park regime should be viewed with nuanced discernment, there is no doubt that the development of his film activities followed in the steps of an ideology focused on intensifying the structural and industrial modernisation to free South Korea from its foreign dependency. At its own level, Shin Films is comparable to the chabeol (a large conglomerate), a heroic and patriotic form of family entrepreneurship epitomised by the Hyundai and Samsung groups. Yet with one small difference – Shin also had a strong spirit of independence. In an increasingly authoritarian context, he would doubtless have taking advantage of a favourable conjuncture. It would above all have enabled him to continue what was most important to him – making and producing films.

Bitter victory

The 1970s turned out to be a difficult decade for Korean cinema. Not only did the Park regime become more rigid with each passing day for all of Korean society, but Pyongyang’s constant provocations only added to its paranoia in an already tense situation. Censorship was both authoritarian and unpredictable. The legislation regulating the film industry was constantly changing, so much so that those who followed it in order not to risk losing their interests were totally disoriented. The dominant position of Shin Films made the filmmaker and his projects particularly vulnerable and his expansion soon became a source of financial worries. Shin’s acquaintance with Park no longer offered sufficient protection. He, like any other, was not above the law or pressures. On several occasions, he adopted an anti-censorship stance, which exposed him to reprimands under the often indifferent gaze of his colleagues, who delighted in seeing him pay for his opportunism. Shin discovered that the system he had inspired had become the plaything of one more powerful than he would ever be. He tried to find ways around it. To counter the limit set on each producer to make no more than five films a year, Shin split his company into smaller entities that together were able to produce twenty films each year. Despite this, Shin Films and its subsidiaries continued to lose money. The films met with less success. The aging Choi Eun-hee also appeared more rarely. The filmmaker’s isolation became even greater.

The final straw came with the scandal that put an end to their union. The rumour grew of a liaison between the filmmaker and the young starlet, Oh Su-mi. The day that Oh Su-mi gave birth to a child, Choi became truly alarmed and understood that Shin, who had loved but her, had betrayed her. The Park family’s sincere respect for the actress placed the filmmaker in an even more awkward position. Two other events were to undermine him once and for all. The first involved A Thirteen Year Old Boy (1974), a film that Shin sent to the Berlin Festival selection without first obtaining the Ministry of Information’s visa, as required by law. The film was selected, and the invitation was addressed to the Ministry. President Park did not forgive Shin’s misbehaviour, any more than his next misdeed in 1975. Shin had reinforced his already long-standing links with Run Run Shaw and coproduced with the Shaw Brother in Hong Kong his Rose and Wild Dog (1975). A kissing scene in which the actress Oh Su-mi appeared with her breasts bared should have been cut, but Shin launched the film without removing the scene. It was immediately banned from screening and, more importantly, the filmmaker lost his company’s film licence and his empire gently cracked apart.

Kim Jong-il

The filmmaker had a second child with Oh Su-mi, and the inseparable Choi and Shin divorced in 1976. In January 1978, Choi visited Hong Kong, invited by a certain Wang Dong-il on the pretext that he wished to back her acting school then in jeopardy due to the collapse Shin Sang-ok’s business. Choi never returned from her trip. All trace of her was lost on 14 January. Worried, Shin Sang-ok then took off for Hong Kong to find out more about the circumstances of her disappearance. Cornered on all sides, he also sought out new alliances in Hong Kong in view of continuing his activities and tried to obtain a visa to leave South Korea and work abroad. Hong Kong, Europe, the United States… several trails were followed in vain. On his arrival, the authorities questioned him about Choi Eun-hee and increasingly favoured the likelihood of a kidnapping by the North Korean secret services (a common practice at the time). Following his first stay in Hong Kong, Shin travelled to Japan before returning to the British colony a few months later. Six months after Choi that same year 1978, he also disappeared. The couple’s prestige, Shin’s reputation as filmmaker, entrepreneur and shrewd producer had made them prime targets for Kim Jong-il, son of the Great Leader Kim Il-sung. He governed the country at his father’s side, and aspired to give North Korea a powerful film industry. Shin Sang-ok’s skill and experience stood as valuable assets for bringing this plan to fruition. Had Shin Sang-ok himself, after his disgrace in South Korea, prepared the scenario of his own kidnapping? Twice, Shin had apparently tried to escape before being held captive for a good while and subjected to torture and intimidation. The pair were imprisoned separately. Choi, who was reluctant to swear immediate allegiance to Pyongyang, was kept under close surveillance in a gilded prison. It was not until 1983, that Shin and his wife were reunited and then remarried by Kim Jong- il. Shin Films was re-established the same year in North Korea in a large studio built at great cost and fitted out with the best technical equipment. Exactly thirty years after the partition of Korea, as in a baffling game of mirrors, Shin Sang-ok once again took up his profession of filmmaker under the same name and the authority of another totalitarian state. In three years, he made seven films in North Korea and produced some fifteen others.

Escape

In 1986, taking advantage of a trip to Berlin with a North-Korean delegation, the couple sought refuge in the US embassy in Vienna and asked for asylum. They went to live in the United States, for a time under CIA protection. Before producing the 3 Ninjas series of three kung-fu films for children, successfully distributed by Disney (he made the third opus), in 1990 Shin Sang-ok embarked on a Japan-produced project for a luxurious Genghis Khan that he had written during his stay in North Korea. The production was definitively interrupted a little after the start of the shoot. In 1994, Vanished was invited to a special screening at Cannes Festival, where Shin Sang-ok sat on the jury. Indirectly but certainly, this recognition helped to rehabilitate the filmmaker. Ironically, Vanished tells the true story of Kim Hyung-woo, a former ally of Park Sung-hee and for a time the head of South Korea’s Central Intelligence Agency, who disappeared in Paris in 1979. Kim had previously lived in exile in the United States, where he had testified about the South Korea’s corruption of US congressmen, which led to Koreagate. Kim Jong-il apparently advised Shin Sang-ok to read the biography of Kim Hyung-woo, Power and Conspiracy.

From his 1961 film evoking the tyrannical monarch Prince Yeonsan, and its sequel made one year later, until Vanished, the stories of Korea conveyed by Shin Sang-ok draw in parallel to the filmmaker’s personal trajectory one of Korea’s most unimaginable and edifying (filmic) novels of the 20th century. And didn’t he carefully name his autobiography I, was a film.

Jérôme Baron

(1) The beginning of Japan’s takeover of the Korean peninsula dates back to the second half of the 19th century, with the protectorate being created in 1876. The treaty of annexation signed under constraint in 1910 assimilated Korea into Japan until the end of World War II and the Japanese surrender of 2 September 1945.