When wondering about the signs and expressions of African-American culture, one obvious fact immediately and inevitably springs to everyone’s mind: the universal influence of black musicians and their crucial contribution to the United States’ cultural history and its entertainment industry. From Sydney Bechet and Duke Ellington to Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald, from Aretha Franklin to Otis Redding, Marvin Gaye to James Brown and Lee Fields, from John Coltrane and Miles Davis to Albert Ayler, Monk, Parker and Archie Shepp, from Prince or Public Enemy to the pop kings Beyoncé and Michael Jackson… we could go on forever adding to this long list to show the priceless legacy that American musical prodigies have handed down to the our 20th-century heritage.

Literature also had its ways of voicing and making heard that the Black American is a construct of the New World. It constantly held up a broken mirror for the United States to contemplate a history polarised by the “Black Question”. From Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, Charles Chesnutt, Ralph Ellison, W. E. B. Du Bois, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Alice Walker and Richard Wright among many others, the issues of slavery, segregation, endemic racism and its litany of discriminations permeating the social, education and economic spheres against the black minority have constantly welled up under the pen of great American writers.

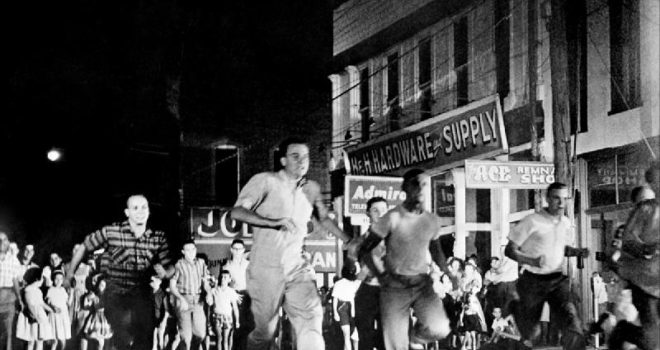

And where does cinema stand in all this? Hollywood’s hegemony endorsed the exclusion of Blacks, making them even more of a minority and marginalised on the screen than they had ever been in a society that had long deprived them of their rights. Flatly turned away, besmirched by an out-of-focus background, or subservient to the continuity cut of an opening door, they had to prove their credentials just to nail the part of a domestic servant in Hollywood’s house. American cinema is above all devoted to manufacturing white heroes, moved by the idea of offering to the dominant majority models of fictions in which it can recognise its life, dream it, idealise it. Contrariwise, for many years it offered Blacks no more than a stereotyped, folkloric, paternalist, not to say racist, representation. Already, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), which produced an unparalleled impact, had certainly marked the birth of cinema as a language, but had also stamped it with a swampy and anti-Black ideology. Its coloured characters are mostly played by black-faced Whites and their behaviours split between an infantilising docility and an odious moral and sexual duplicity. The fulfilment of the national destiny, the unification of South and North is only possible thanks the salutary intervention of the Ku Klux Klan in the face of the black peril. America seemed to regain its cohesion, uniformity and a future on the back of the Blacks…

Jérôme Baron

Read More

Concerning the situation of African Americans, Hollywood has never really challenged the established order. And it is easy to point to the effects of this resignation, ranging from defensive repression to burying one’s head in the sand, from an irreconcilable discomfort to a sincere indignation bent on correcting a deficit or deformation of the way that black Americans are represented in cinema, as is the case of a broad palette of films: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Stanley Kramer, 1967; Lilies of the Field, Ralph Nelson, 1963; Sounder, Martin Ritt, 1972; Mississippi Burning, Alan Parker, 1987; The Color Purple and Amistad, Steven Spielberg, 1985, 1997. Yet, this has never guaranteed the quality of the films.

The strategy of conquest in American cinema is still characterised by a process of domesticating the majority (including the elite), a conception of politics basically portrayed as a power struggle and a conception of the individual as a product of social influences. The studios, buoyed by this belief and legitimised by the formula’s success, or many years failed to consider African Americans as a public eager to recognise in films something of itself or a culture that could be their own. Taking for granted the idea that spectators are mainly motivated by the desire to be captivated by a story, black audiences participated, like the rest of Americans, in the undivided rule of white heroes, in the exploits of Tarzan, and for many years seemed to have Uncle Tom’s cabin as their sole counter-shot.

Yet, there have always been African American talents and ambitions among filmmakers, actors and screenwriters to drive the emerging expression of black history and culture in cinema. Since the recent burgeoning of black cinema that we have all witnessed first-hand, we in turn wanted to revive a pioneering mission of Festival des 3 Continents by reconnecting with a century of African American cinema history through some forty films. This anthology offers an opportunity to give perspective to the synchronicity between the unheralded emergence of a new generation of filmmakers and Barack Obama’s two terms as president of the United States. Lee Daniels’ The Butler and Precious, Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave, Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight 1, the worldwide success of Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther or Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, along with many others, have all been emblems of this regained vitality of black cinema. In total, no fewer that 165 “black” films were made between 2009 and 2016. There may have been an Obama- effect on cinema, but its impact assuredly seems more diffuse if we add to this incredible constellation of films signed by black directors the films made by Whites who tackle this subject either obliquely, as in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, or head-on, as in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, Jeff Nichols’ Loving, Peter Farrelly’s Green Book… This rallying point, with no roll call, helps to create a new horizon where the spectre of a white racist America is seen from the vantage point of a history revisited (slavery, segregation,

civil rights struggle, police violence) by cinematographic expressions now far-removed from references to the 1970s Blaxploitation and to those of the New Jack films and their corollary twenty years down the road.

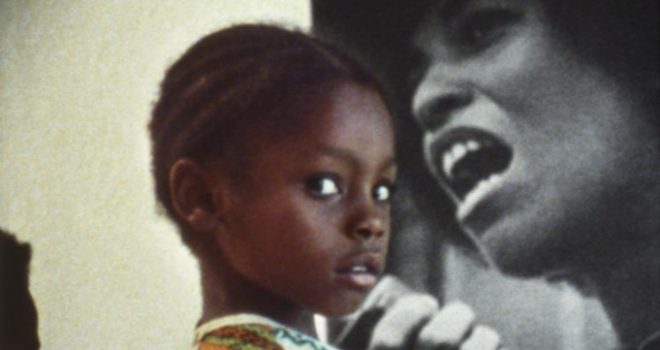

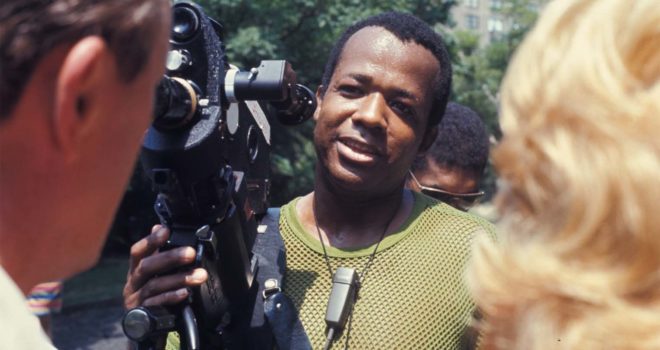

The main purpose of this anthology is to show the value of works by African American filmmakers, where the need for discovery and recognition go beyond the scope of the cinephile world. Yet, we were reluctant to exclude the possibility of offsetting the dearth of black films, notably in the 1960s, with the gestures of some white filmmakers that are significant on many counts. This is the case of Douglas Sirk’s masterpiece, Imitation of Life (1959), where by being fake everything become so true that even on the appearances front of the colour line – which here separates a mother and daughter who want to pass for Whites – the filmmaker works on ambiguity with unparalleled subtlety and emotion. The films Nothing But a Man and The Cool World are different. The first, by Michael Roemer, is virtually unknown and one of the most accomplished films about the life of black workers in American fiction cinema. The film by Shirley Clarke, following The Connection and before many more, is a crucial milestone in the work of a filmmaker who paid passionate and lasting attention to the black community and its culture.

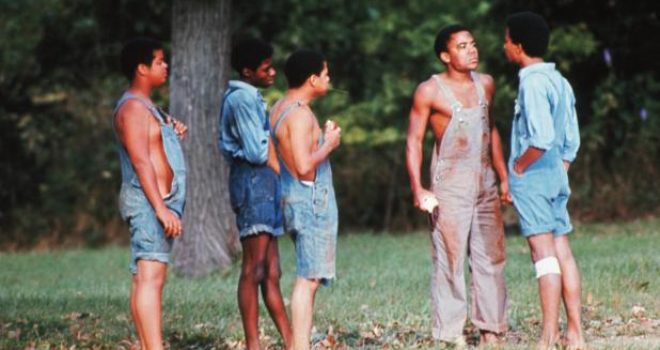

Inevitably, our starting point will include a selection of race films made between the early 1920s and early 1940s. Like the films of Oscar Micheaux (dubbed the “father of independent Black Cinema”) and Spencer Williams, these films most often took the paths of melodrama to reach an all African-American audience during the years of segregation and the first waves of migration to the North. Only a limited number of race films have been rescued from disappearance. Produced by Whites and Blacks, mostly directed by Blacks, they are the only cinematographic witnesses of the African-American experience during the first half of the 20th century.

From the very end of the 1960s until the first third of the 1980s, black cinema experienced one of its most intense periods of creativity. As Serge Daney pointed out in the catalogue of the 3 Continents Festival’s first edition, its momentum is to be found in the “inseparable [nature] of two hard facts”: the growing political awareness of a black community at the crossroads of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panther Party, and the very first opening-up of a crisis-ridden American cinema to the opportunity of integrating what it had formerly rejected. Daney explains: “This is why the emergence of this Afro-American cinema had two faces: the commercial (Blaxploitation) and the independent” (represented in our programme, on the one hand, by a group of key films from the L.A. Rebellion at UCLA, and films that defy categories and attachments, on the other hand, such as those by William Greaves, Bill Gunn, Melvin Van Peebles, Fronza Woods and Kathleen Collins).

The early 1990s was another landmark moment that can today certainly be viewed as a decisive step in the integration of black filmmakers into contemporary American cinema. After thirty years, Spike Lee remains the media figurehead of this turning point, which also corresponds to the incomprehensibly late entry into the Hollywood star system of many actors we have long been familiar with (except for Sydney Poitier and Harry Belafonte): Eddie Murphy, Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington, Whoopi Goldberg, Forrest Whitaker, Will Smith or Halle Berry, the only black actress to win (in 2002) the Oscar for the Best Actress.

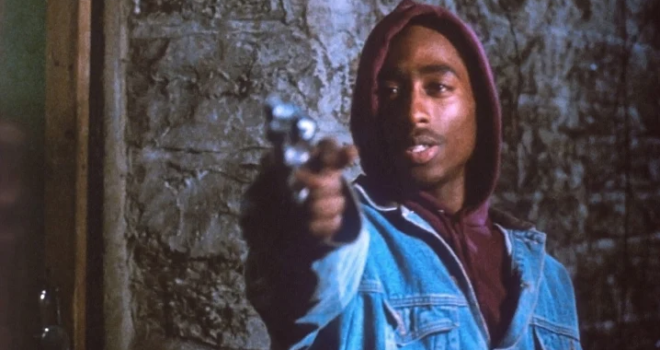

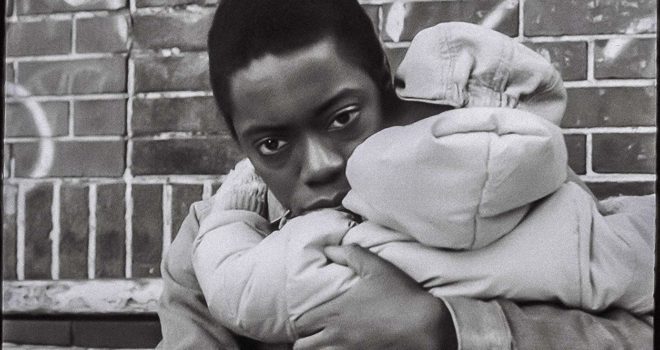

Fifteen years after the ghetto of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977), the ghetto of the films by the Hughes brothers, John Singleton or Ernest R. Dickerson replaced the blues of Stan the slaughterhouse worker with a now furious version of urban anger who took up rap as its banner. Filming the micro-society of the ghetto adrift, over twenty years after the Watts riots, the rage had turned fratricidal, the music and images had become a way of defending a lifestyle opposed to the white model of success that continued to exclude a large part of black youth, the signs of exuberant provocative wealth and a “complex-free sexuality” passing off the rebellious and dissenting behaviours of Blaxploitation for bravado. Out of the ghetto films was born another form of counter culture and a way of expressing their demands. They laid the ground for what has emerged in recent years.

This Black Book of American cinema begins to tell a story that the films gathered here, like gaps and margins open to our eyes and thoughts, will help to fill out. They are its raison d’être.

Jérôme Baron

In 1979, Serge Daney, then Editor-in-Chief of Cahiers du Cinéma, has contributed to the programming of a first retrospective of Black American cinema in Festival des 3 Continents, in Nantes. Forty years later, the relationship between the magazine and the festival remains unwavering. It seemed natural to both entities to include, along with the films of the present retrospective and as a testimony to their long affinity, certain texts written for the No. 738 (November 2017) of Cahiers du Cinéma, precisely devoted to the same subject. Our sincere thanks to the editors Stéphane Delorme and Jean-Philippe Tessé, accompanied by the writters Camille Bui, Cyril Béghin, Joachim Lepastier, Stéphane du Mesnildot and Hugues Perrot.