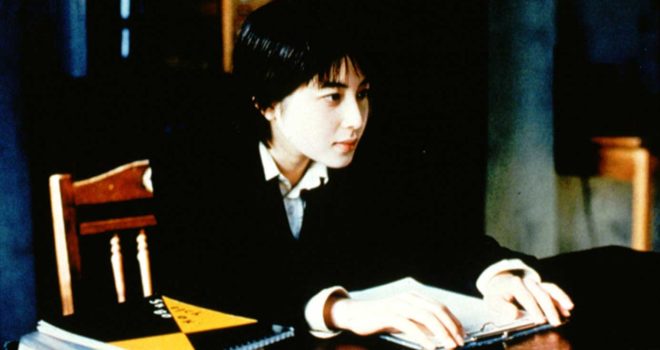

Nobody Knows (Dare mo shiranai) by Hirokazu KORE-EDA © trigon-film

French audiences first discovered the work of Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda in the mid-90s. Maborosi (Maboroshi no hikari,1995) and After Life (Wandarafu raifu,1998) were screened in their year of release at the Festival des 3 Continents, the latter earning a Montgolfière d’Or award and establishing the filmmaker’s renown. Shortly thereafter, Distance (2001) and Nobody Knows (Dare mo Shiranai, 2004) were selected for the International Competition of the Cannes Film Festival. With the release of each new film, French audiences developed an increasingly strong loyalty to the filmmaker, whose works paint a subtle portrait of Japanese society. This connection grew even stronger with the release of Shoplifters (Manbiki kazoku, 2018), which won the Palme d’or at Cannes that year. As we await the release of Broker (December 7, 2022), we will have the pleasure of seeing his little-known – if not unknown – documentary work. Hirokazu Kore-eda will be present in Nantes from November 25 to 27.

Editorial Hirokazu Kore-eda, a Country at Heart

A couple who make their living from shoplifting adopt a young girl illegally, and at the margin – but right in the heart – of the Japanese capital we see the makeshift happiness of a family of squatter-thieves unfold. In 2018, the Palme d’Or awarded to Shoplifters crowned the evident maturity of a filmmaker who is one of the best-loved and best-known, especially by French audiences, thanks to the hospitality and gaze of his films. As Broker is soon to be released in French cinemas, this retrospective should help deepen and shed new light on this long-term adventure, in the company of Hirokazu Kore-eda. In Nantes, the adventure began in 1995 with the discovery of his first fiction, Maborosi. Then came the Montgolfière d’Or awarded to Kore-eda’s second cinematic work, After Life (1998).

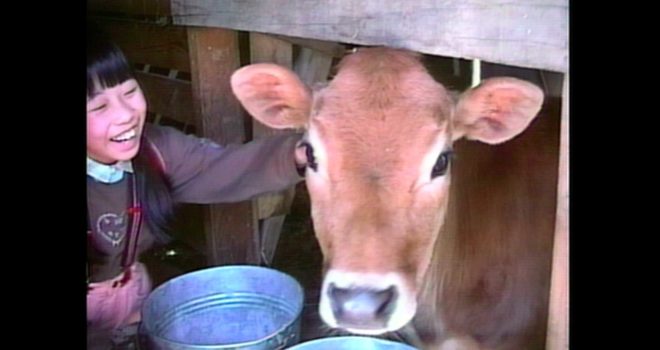

Yet, a whole swathe of his work remains unseen, almost unknown to our screens: after graduating from Waseda University in Tokyo, Kore-eda (born in 1962) first worked with Japanese television (for the production company TV Man Union), which in his view was reaching the end of a golden age. Influenced by various documentary programmes from his youth, Kore-eda had the good fortune to meet a handful of producers and programme directors who were continuing to move in this direction. In the early 1990s, driven by an intense and fertile curiosity, he made his first films, setting out to meet his compatriots: the widow of a public health bureaucrat whose suicide raised questions for him (However…), children taking part in the experiment of raising a calf in their school (Lessons from a Calf), the first gay man in Japan to publicly announce that he had AIDS and was living the last few months of his life (August Without Him). These first television documentaries are still a well-kept secret, although it is there that we find the first child characters of his oeuvre, the first profound evocations of mourning and memory, even a searing family drama (Without Memory). While these documentaries certainly shed light on his fiction work and provide a useful entry point, these two filmmaking periods and practices cannot simply be placed end to end (in fact, they are mostly concomitant). Far more than sketches, many of these first films are pearls of writing and invention. Above all, his intertwined oeuvre draws a penetrating portrait of Japan and the Japanese – ordinary Japanese and a whole poor population, all the “John Does” of the Nippon archipelago – men, women and children of all ages, families, businessmen, bureaucrats, marginalised or abandoned individuals, sometimes criminals in the eyes of the law or ordinary heroes in the news. “A country at heart” is at the same time a gaze that extends a long way and right into the heart of Japan, and the intimate relationship that Kore-eda builds with the subjects he carries within himself. Even when he looks at the administration (which few do in any depth), Kore-eda is interested in individuals, and captures its dysfunctions through the concrete experience of a human story. In his cinema, this often means, for a handful of these people, finding or re-finding a form of common life. He also intertwines personal ups and downs, the exploration of relations within a family or a small community, and a view of society. The camera is a “tool for encountering the world”, and the eye that that probes the exterior has its nerve rooted in a sensitivity whose obsessions persist: Kore-eda never ceases to observe the world around him and, in turn, injects his dread of separation, memory and time. We are thus gripped by the overwhelming precarity of a happiness shared.

Like Ozu, who he is often compared to (despite his objections), Kore-eda sees that the essential is contained in all the small things which show us that our quotidian is also our life – and he often shows its disruption, which sometimes leads to its reinvention. His films avoid sordidness by instead revealing the love and imagination circulating between the characters, as in Nobody Knows or Shoplifters – the films marked by the harshest reality are sometimes short-lived utopias. Conversely, it is not hard to see that the gentleness and sensitivity of his films often go hand in hand with a form of roughness or violence, sadness or cruelty. Gestures of day-to-day existence and life in common, light, objects, places where the characters live – places that are never indifferent – form the real framework of the mise en scène. A film such as Our Little Sister is a shining example of this, but his approach also helps us to better understand Like Father, Like Son – an ode to the ordinary revealed by an extraordinary situation. For Kore-eda, both terms are very often two facets of the same approach to life.

From one film to another, one production environment to another, one “genre” to another, Kore-eda puts his questioning to good use in an attempt to break down siloes. Fiction and documentary enrich each other, or even combine in a hybrid form as in After Life. The filmmaker also allows himself an incursion into the samurai and ghost film genres: Hana, never released in France, or The Days After, made for television, are other little-known films in his filmography. As a discreet experimentalist, Kore-eda is constantly questioning his art: this comes through in his book, When I Shoot My Films (Atelier Akatombo, 2019), which is fascinating on account of the honesty and simplicity of his approach. It tracks the thread of his filmmaking and shows each of his films as an opportunity for reassessment and surprise, while also describing the challenges of film production and distribution. Kore-eda has a generous spirit of transmission and unsurprisingly we see him campaigning today alongside Nobuhiro Suwa or Koji Fukada for the creation of a national centre for Japanese cinema, in line with the model (always to be defended…) of the French CNC.

A final point: as he films a broad diversity of real or fictional individuals, Kore-eda is a skilful director of actors, whatever their age or level of experience. Working relationships are privileged (Kirin Kiki, Lily Franky…), as is the art of group casting (unforgettable “families” built from scratch). There is no dogma as the director is constantly developing his method, from controlled improvisation to a highly detailed script: all that counts is the freedom of the work and the teeming life that it has to produce. He listens to his film and his performers, and the latter reciprocate, redoubling their creativity and confidence.

Jérôme Baron & Florence Maillard