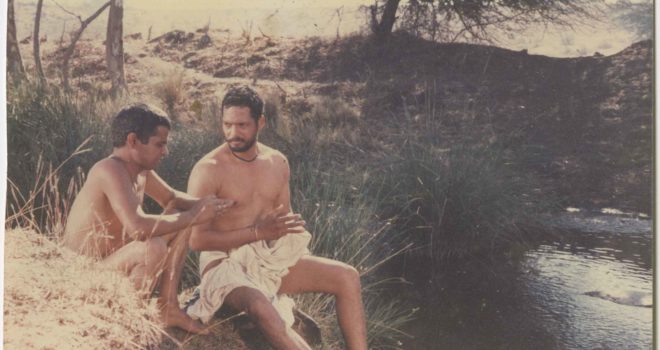

The Bogeyman (Kummatty) by Govindan ARAVINDAN © Film Heritage Foundation

Autumn, the most clement season in India, is the perfect time to take a tour of Indian cinema from 1970 to 1990 through films that are unknown, forgotten, or overlooked. Fourteen films pay tribute to the aesthetic diversity of a filmmaking industry that is too often reduced to Bollywood. Filmed in a range of languages including Hindi, Malayalam, Urdu, Bengali, Tamil, and Gujarati, the films in this programme speak of the immensity of a country whose cinema industry is rich and multifaceted. And if dances, songs and love stories are part of these films, what truly excites us is the profound desire of moviemaking that they emanate. Selection made in collaboration with the Film Heritage Foundation.

Editorial An Indian Autumn

We are very proud that the Film Heritage Foundation is co-presenting with Festival des 3 Continents an eclectic selection of 14 Indian classic films showcasing the diversity of our rich film heritage. It all began when I first met Jérôme Baron, the Artistic Director of the Festival at the screening of Film Heritage Foundation’s restoration of Aravindan Govindan’s Malayalam film Thamp (1978) at the Cannes Film Festival in May this year. Over a conversation, Jérôme suggested that we could collaborate on an array of classic Indian films for the next edition of the festival. I thought it was an incredible opportunity given the Festival des 3 Continent’s remarkable programming since 1979 which also includes memorable retrospectives of Indian films. Subsequently Jérôme came to India and I was astounded to discover that he had an encyclopedic knowledge of Indian cinema. The cornucopia of Indian films at the festival has emerged from the many stimulating discussions we had together.

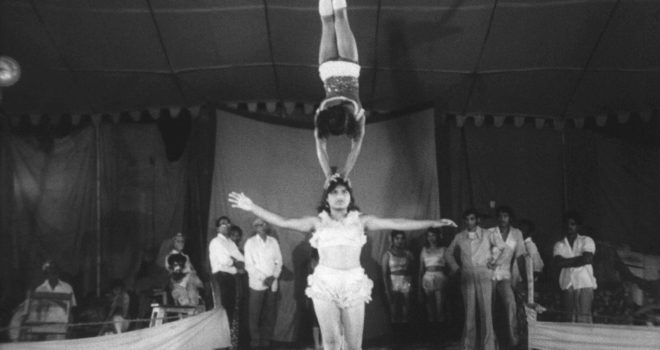

The selection reflects the complexity and diversity of Indian cinema: from the quiet poetry of Aravindan’s Malayalam films, The Bogeyman (Kummatty) and The Circus Tent (Thampu) to political films like the Tamil film Water Water (Thaneer Thaneer) directed by K. Balachander and Sanjiv Shah’s Gujarati film Love in the Time of Malaria (Hun Hunshi Hunshilal) ; from experimental/ avant-garde films like Mani Kaul’s One Day Before the Rainy Seasons (Ashad Ka Ek Din) to cult films like Kamal Swaroop’s Om Dar-B-Dar and John Abraham’s film Donkey in a Brahmin Village; from Girish Karnad’s lavish erotic drama Festival (Utsav) to Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan that explores the existential angst of a wealthy young man, we have attempted to capture in a microcosm the vast breadth of Indian cinema.

Sadly, India has a very poor record of film preservation and the numbers say it all. 1338 silent films were made in India of which just 29 survive, many in fragments. Of the films made till 1950, we have lost almost 70 – 80%. Original camera negatives and even prints of more contemporary films have vanished without a trace.

Consequently, curating a collection of Indian classics is always a challenge for several reasons: the colossal loss of our over 120-year-old film heritage and the sheer linguistic and geographical diversity of India’s film industry, which produced 2446 feature films in 55 languages in 2018-19, making India the most prolific film-producing nation in the world. There is a popular misconception that equates “Bollywood” or the Hindi film industry based in Mumbai with Indian cinema. However, the story of Indian cinema began in three major port cities: Bombay, Calcutta and Madras where the early studios flourished. Over time cinema centers grew around the country and today India has about 10 major film industries spread across the country. The four South Indian industries are currently a dominant force. It is no surprise then that a film curator is faced with a conundrum of plenty and scarcity depending on one’s perception.

We thought it would be interesting to put together a diverse range of films from the 1970’s to early 1990’s, which was a turbulent socio-political time in India that gave rise to a very unusual period for cinema with the emergence of the New Wave, the Middle Cinema and the Angry Young Man (whose iconic incarnation on-screen remains the superstar Amitabh Bachchan). It was a time characterized by industrial stagnation, student unrest, unemployment and political violence. Protests against the government reached a zenith and the Indira Gandhi government responded by imposing Emergency that brought with it a brutal clampdown on freedom of expression and dissenting voices.

However, a convergence of forces: state intervention, turbulent socio-political conditions, a progressive film school and an active film society movement created an explosive movement of parallel cinema in India. The films that emerged represented a cornucopia of cinematic experimentation with new forms of film narration as well as cinematic realism in diverse languages and styles yet with a shared view of cinema as art and social/political critique.

Indian New Wave was a movement peopled by remarkable filmmakers who made films that have left their mark on the pages of cinema history beginning from very important filmmaker Mrinal Sen’s satirical work Bhuvan Shome in 1969, the experimental work of Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani and the more linear narrative style of Shyam Benegal to name just a few.

It is with great difficulty that we narrowed the list for this festival down to 14 films. There were two more films that were part of the original list: Sai Paranjpye’s first feature film The Touch (Sparsh,1980) that launched her career and K. Balachander’s musical melodrama Sindhu Bhairavi (1985), both of which we had to drop, as tragically we could not find any material that would be suitable for a cinema screening.

This is a recurring problem we face at Film Heritage Foundation where we find that so many films have fallen through the cracks over the years through neglect and apathy making it imperative that the preservation and restoration of films be taken up a priority if we are not to lose our films forever. This is the reason Film Heritage Foundation joined hands with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna to restore Aravindan Govindan’s poetic masterpiece The Bogeyman (Kummatty) and then took on the mantle to restore his cinema-verite styled gem The Circus Tent (Thampu) as no original camera negatives of these films survived and even the prints were in a precarious condition. It is with great joy that we now see these films enjoying a second life as they travel all over the world to be seen by new audiences.

We are so glad that we are able to include the restored version of Ritwik Ghatak’s A River Called Titas (Titas Ekti Nadir Naam,1973) in the festival this year as well as an older restoration of The Ruins (Khandhar, 1984) to mark Mrinal Sen’s birth centenary year.

The making of some of these films could be films in themselves. In the case of John Abraham’s Report to Mother (Amma Ariyan), it was the first film produced by the Odessa Collective started by the filmmaker and his friends as a people’s cinema movement aimed at freeing film production and distribution from market forces. They raised funds for the film by travelling from village to village per- forming skits and street plays and collecting money from the public. Love in the Time of Malaria (Hun Hunshi Hunshilal) Sanjiv Shah’s genre-defying absurdist satire on an intolerant regime that cracks down on dissenters was made on a shoestring budget and dropped out of circulation for decades. It is with great satisfaction that we bring it back to the big screen. Kamal Swaroop is at his iconoclastic best with the cult classic Om Dar-B-Dar – film that escapes definition.

Kunal Kapoor’s painstaking restoration of the films 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981), Aparna Sen’s directorial debut – a poignant study of loneliness and nostalgia – and Girish Karnad’s Festival (Utsav,1984) produced by his father, celebrated Indian actor Shashi Kapoor, will be also showcased.

Some of these eminent filmmakers will even travel to Nantes to present their films, and make this edition a very special one. It is going to be wonderful to have Sai Paranjpye be present for Disha (1990), her film on the very relevant issue of the plight of immigrant workers in urban India, which the filmmaker says is her most important work; Sanjiv Shah to present Hun Hunshi Hunshilal and renowned filmmaker and author Saeed Akhtar Mirza present his compelling film Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan (1978) in person.

These filmmakers who rebelled against the constraints of commerce and created films with an artistic and political impact have left a legacy that must be cherished and revived.

And this celebration of the rebellious poets of Indian cinema in Nantes reaffirms Film Heritage Foundation’s commitment to the preservation and restoration of India’s rich film heritage, especially those films that won acclaim, but live on the fringes of the mainstream, and hence are in even greater danger of disappearing as the commercial world turns its backs on them.

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur is a filmmaker, archivist and the Founder Director of Film Heritage Foundation