NOSTALGIA FOR COUNTRYLAND de Dang Nhat Minh

We know little of Vietnamese cinema; while French audiences are familiar with Trân Anh Hùng’s films from the 90s, our collective vision of Vietnam is deeply influenced by American films about the Vietnam War, or, for the most dedicated movie buffs, by a certain militant European cinema from the 60s and 70s. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and France, the Festival des 3 Continents travels back along the rich and complex trajectory of this cinematography that anchors its ambitions in the context of the dividing up of the country and a series of armed conflicts. Whether an act of resistance through images, focusing on figures that were important to the people, or affirming their identity and cultural diversity, Vietnamese cinema has always sought greater unity by examining contrasts and antagonisms.

Editorial – Anthology of Vietnamese Cinema

When the terms “Vietnam” and “cinema” are mentioned, what invariably springs to mind are American films, mostly made between 1975 and 1995, so after a war that for many American filmmakers was to be the war of a generation. Considering the large number of these films, we could well question French cinema’s lapse of memory on the subject of the Indochina war as well as other colonial conflicts.

Moreover, it is at the margin, on the fringes of militant cinema from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, that Vietnam attracts attention with the films of Emile de Antonio, Robert Kramer, Michael Grigsby, the Winter Soldier Collective from across the Atlantic, or the famous Far from Vietnam (1967) co-directed by Godard, Ivens, Klein, Lelouch, Marker, Resnais and Varda.

Later, we think of the so-called viet kiêu films (made by filmmakers from the Vietnamese diaspora born or living abroad) that at the turn of the 1990s provide an updated representation and cinematographic link with Vietnam, emblematically the films of Tran Anh Hung – The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), Cyclo (1995), The Vertical Ray of the Sun (2000) – crowned by international awards.

An obvious question arises out of this brief overview: what was happening in Vietnamese cinema over the same period, what self-representation did the country produce? Vietnamese cinema remains among the most inaccessible in Asia, even though for many years, particularly in France, film clubs such as the YDA have existed and have been working to heighten its visibility. There have also been a few retrospectives, including a pioneering one at the 3 Continents in 1992. Eager to revisit these films and take a closer look at them together, we have assembled this little anthology of Vietnamese films to celebrate in collaboration the Vietnam Film Institute the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations and the 10th anniversary of the strategic partner- ship between our two countries.

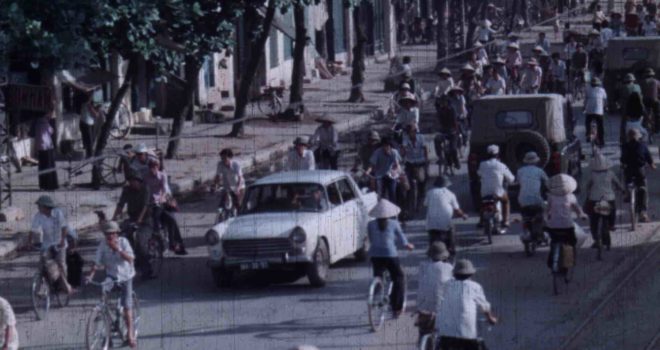

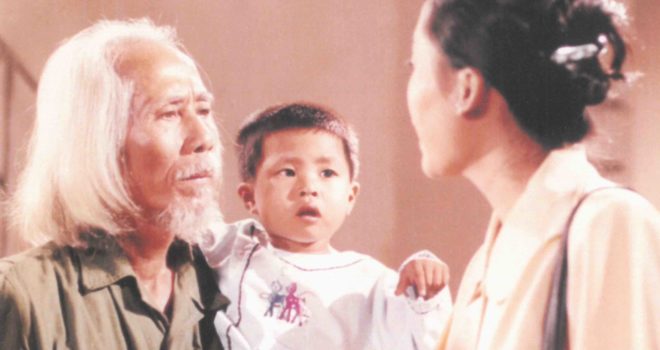

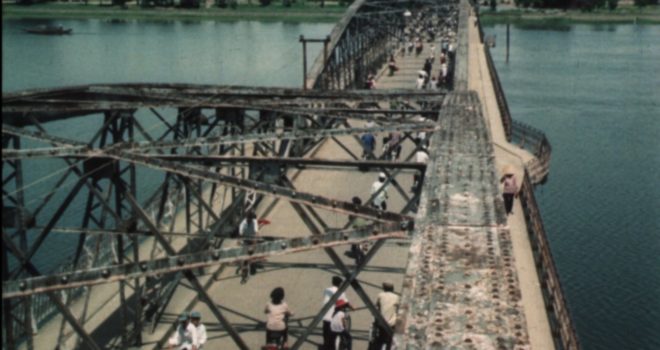

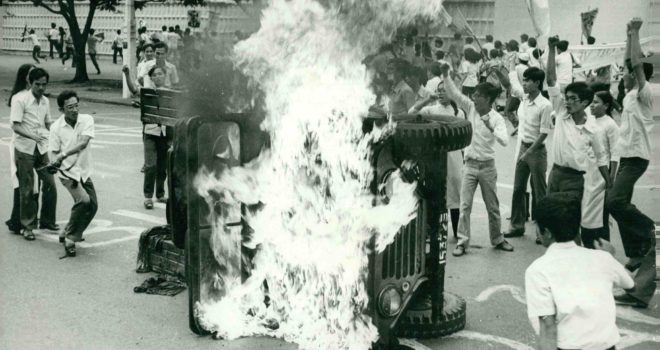

The 18 films + 1 (Dust & Metal, 2022) in this programme span twenty-five years of Vietnamese cinema (1974-1999), from the period of state-controlled cinema to the time when the economy of the film industry began its transformation in fits and starts under the influence of the Dôi Moi reforms launched ten years after reunification (1975) at the Sixth Communist Party Congress in 1986. From one milestone to the next, this decade has a single constant: whatever the orientations of Vietnamese cinema (supporting a patriotic cinema of war, questioning the traces left by thirty years of war in a civil society in need of renewed cohesion, rereading past historical events, opening up to other ambitions), they are driven by political thrusts to adapt to the historical context. And in 1975, in a country that had triumphed over the American occupier, the resources and equipment remained precarious despite measures to nationalise the film institutes and studios (including Giai Phong Studio created that same year). To conjure up this historical moment, we select- ed two films made 20 years apart by two emblematic filmmakers: Dang Nhat Minh’s The Faces of May (1975), a documentary shot in the euphoria of the Liberation of Saigon, and the fiction feature, The Building (1999), by Viet Linh, who looks at the same event with twenty-four years of hindsight.

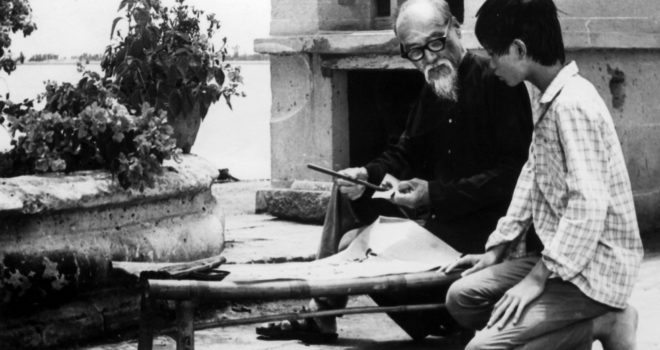

The term “socialist realism” has been regularly used to characterise this cinema at the start of the period. Soviet influence on Vietnamese cinema is naturally not refuted especially as numerous technicians and directors trained at the VGIK in Moscow as early as the 1960s. However, the impact seems fragile and the requirement to produce films tied to social reality, meaning to the transformations that socialism brought to the country, in no way led to an obsequious cinema of slogans. While the conflicts with China and Cambodia perpetuated the motif of struggle against foreign aggressors, the fallout from the war and the problems of reconstruction are also addressed – by the wayside, at an intimate level. At least, this is what several films in our programme show, be it The First Love, Brothers or Fairytale for a 17-Year-Old Girl. Neatly apparent is the documentary imprint left by the pre-war and war years on the aesthetic of the films that are among the most original made between 1975 and the mid-1980s. This is not surprising. Compared to the number of fiction films made in the North between the start and end of the war, the number of documentaries is overwhelming. With the reversal of this trend in the late 1970s, the experience acquired by a cinema of struggle fed into the cinema of reconstruction. As if all fiction at odds with what actual experience was called to order either by the sudden surge of reality (in the background of a shot, left or right of the frame, in the natural gestures and settings) or by economic constraints.

From 1986, the Dôi Moi policy had the effect of loosening up a very hierarchical political system based on a highly compartmentalised vision of the economy. In the realm of culture and cinema things also begin to move, but this was not without contradictions. On the one hand, commercial film production increased often to the detriment of any artistic ambitions. On the other hand, films with an artistic spark had little access to technical and financial resources. However, these years saw an upheaval whose developments laid the ground for the emergence of an auteur cinema, as for example Dang Nhat Minh’s The Girl on the River (1986).

Yet, the Vietnamese films of the 1980s have never been widely distributed and their screening has been stymied at times in Vietnam. It is by searching for rhymes, echoes, correspondences between the films that we sought to compose a picture of Vietnamese cinema in which each film would be a detail.

Jérôme Baron