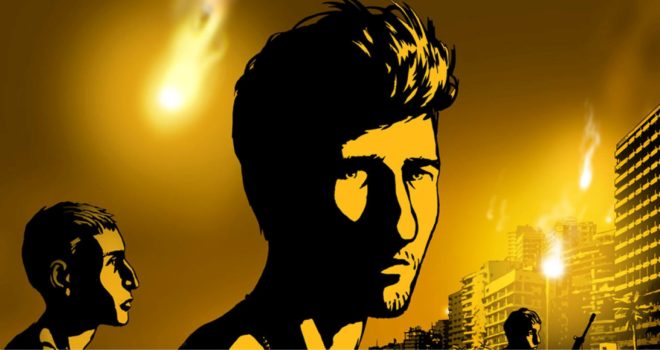

In Sunless, Chris Marker reminds us that memory – remembrance and forgetting – are two sides of the same coin: the treasure for those who, even if they cannot remember everything, have not forgotten everything, either. In other words, cinema as an archive, providing food for thought about the present, constantly weaving the threads of time: Satyajit Ray’s tale of lost love, Johnnie To’s story of revenge, Ari Folman’s memories of war, or Rithy Panh’s piecing together of a past that has been erased. This intertwining of memory, remembrance and forgetting is the very substance of the films in our programme. This one, like the others, is for all audiences. The Festival has produced an educational booklet for secondary school teachers, as this selection is also an invitation to their pupils to take part in the 3 Continents.

Editorial – The Meanderings of Time

Although their definitions differ, the notions of memory, recollection and forgetfulness are nonetheless correlated and porous. Their entanglement draws lines with sensitive intersections, their tracks slide from an inner subjective experience to collective experience, from what we consider our personal duty to what we have to transmit to others. So, though we often talk about the duty of memory, let’s not forget that no memory exists that has not been constructed through searching (the selection and combination of salient facts considered significant), no recollection returns without stirring up the impression of forgetting (ah, yes, I remember now!). It is in this sense that we insist less on the opposition between memory and forgetfulness, and rather, like Chris Marker in Sunless, recognise that they are in some way the versatile faces of the same coin, the treasure of someone who, whilst not remembering all they have experienced and learnt, knows they have not forgotten everything they have seen, heard or read.

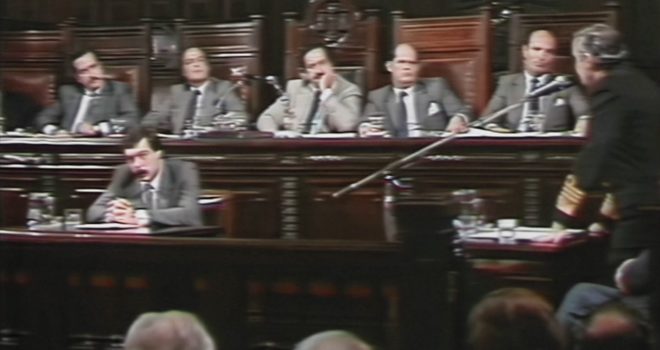

We know the unparalleled fears that the tragedies of the 20th century have stirred in us and the efforts mobilised to curb the threat of a failing memory: forgetting the extermination is part of the extermination itself (Baudrillard). Our fear of memory lapses is like that of disappearing into the night. But what we lose is not so much memory (the world, objects, the host of events, now more widely accessible in our libraries, museums and the digital society), but recollections, meaning the impressions, emotions and our processing of these externalities which all constitute the fabric of time. While our recollections are the products of our memory, “[they] are shaped by forgetfulness, just like the contours of the shore by the sea” says Marc Augé. Thus, the perception of the random ebb and flow of the past into our present is decked out with a cult of the past that should also challenge the values that guide our search for truths as well as for the abuses of memory, whose dangers are pinpointed by Tsvetan Todorov. It is precisely in this area that art is important for us, particularly the art of cinema, which transcends its power to record by also inventing a missing picture, as Rithy Panh says, retrieving memory and traumatic recollections, building signs into stories, reversing time in order to teach exemplary value, referring back to the past but also questioning the future.

As early as 1898, when cinema was not yet an art, a visionary text by Boleslaw Matuszewski titled A New Source of History, The Cinematograph seems to highlight the strong link of historicity that stretches between a technical invention and what it produces: the cinematographic print, in which a scene is made up of a thousand photographic images and unreeled between a focused light source and a white sheet, raises the dead and absent, this simple strip of printed celluloid not constitutes only a proof of history but a fragment of history itself.

Cinema thus became a vast archive of its epoch faster than it could have imagined, while filmmakers soon became aware of the strong creative thrust of their art, investing it with educational and moral stakes, in other words with an aesthetic. From Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942) (among other examples, including earlier ones), through to the more recent Wang Bing or Lav Diaz, cinema has repeatedly picked up and re-tightened the thread of time without disregarding individual, collective and historical memories. Woven differently, these links with the past have opened the way to endless and fundamental re-inventions of what we might have missed or overlooked. At time when we sometimes no longer know whether we are outside (excluded or withdrawn) or inside (aware or taken as a hostage), cinema is what has helped us to navigate in the century’s troubled waters. Between an excess of memory at times and chilling forgetfulness at others, we carry the conviction that cinema will have been (bodies, gestures, words, stories…) one of the historical conditions of humanity. In a context of profound transformation, the powerful entertainment machine will also have been one of a relentless questioning of our times and a place of memory. Not an antidote but a form of resistance against amnesia whereby the past and our recollections could become the bedrock of a real poetic, political and inner imaginary.

Jérôme Baron