MOSSANE by Safi Faye

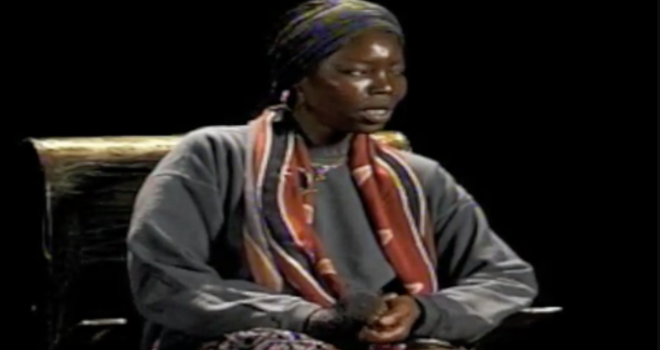

Pioneer filmmaker and the first Sub-Saharan African woman ever to make a feature film (Letter From My Village (1975), winner of the Georges Sadoul prize and the Critics’ Award at the Berlin International Film Festival), Safi Faye passed away last February just as the Festival des 3 Continents was preparing to invite her to Nantes to present her life’s work. After first studying ethnology at EHESS, and then graduating from the Louis Lumière school, she left teaching to dedicate her career to the cinematographic art after meeting Jean Rouch, who cast her in Little by Little. The works Safi Faye created have a strong documentary leaning, and she used filmmaking tools not only to promote the possible emancipation of women, social justice, and freedom from colonialism, but also to reconnect an oral, movement-based, earthly tradition to its power and history. A filmmaker who remained true to her Serer roots, Safi Faye was the perfect incarnation of an African person contending with the challenges of her time.

Editorial – Safi and her Oeuvre

This retrospective dedicated to Safi Faye will, alas, take place without her. The Senegalese filmmaker passed away last February at 79, whilst we were readying ourselves to invite her to Nantes to present her films at the Festival des 3 Continents. Let’s not hide how hard it was to bring together this retrospective. We are unable to present almost half of the works that make up Safi Faye’s filmography, because the films are today invisible, the copies in a state of fragile conservation, difficult to access, if not unfindable or lost. This invisibility calls for a few remarks.

For the past few years, festivals across the world have multiplied retrospectives for women filmmakers, selection committees looking to create parity in their competitions and juries delivering feminised prize lists, and this whole small world sometimes gives the impression that it is a race to see who can list the most names. This trend, which no-one can have missed, is cheering in that it bears witness to a welcome concern for diversity and allows us to discover or rediscover as many bodies of work. But it is also an issue. Programmers and selection committees cannot content themselves with showing all these films in this manner, as if it were nothing. As if these works had suddenly appeared out of nowhere, landing in projectors and catalogues as if the festivals had spent decades awaiting them. No, these films have not sprung up out of nowhere, they already existed. So why on earth were these retrospectives not organised ten, or twenty years ago? And how can they be organised today, from what angle? These are the questions our festival, as much as any other, must ask itself.

The other issue brought up by the rarity or loss of Safi Faye’s films leads us to the films’ origins. Safi Faye was not ignored at the start of her career. Letter From my Village (1975), her first feature film, was rewarded by a number of international prizes. The next, Fad’jal (1979) was selected at Cannes and Berlin. The filmmaker then started to imagine a fiction that would be shot ten years later, Mossane, also presented at Cannes in 1996 (its production marked by misfortune) and only released in 1998. But what happened in between these two milestones – what happened to Safi Faye between Letter From my Village and the retrospective held in her honour by the Festival International de Films de Femmes in Créteil (whose long term work, led by their founder Jackie Buet must be recognised), in 1998? She made corporate films, films for television, commissioned films, all short and rarely seen. It isn’t about rewriting history. But about noticing that Safi Faye shares the fate of many women filmmakers rediscovered recently: one or two original, pioneering films, but something didn’t engage in terms of production, visibility, and then the refuge of shorter, cheaper forms on smaller screens, to keep on expressing themselves. This pattern, where the feature film resembles a glass ceiling despite proven talent, is also an issue, to say the least.

Safi Faye was born in Dakar and worked as a teacher before coming to the Paris of 68 to seek the tools she needed for what she called “the manifestation of her Africanity”. First, the Africanist erudition, through studying ethnology and anthropology at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Études. Then the technical tools of film at the École Louis-Lumière, where she was the first African woman to be admitted. Hired by Jean Rouch as an actress for Little by Little (1970), she directed a short film, the first ever film directed by a sub-Saharan African woman, La Passante (1972). Then, perhaps echoing her sentiments at the Festival des arts nègres in 1966 (“fascinated by all these Europeans who knew all about my culture, a culture I didn’t learn about in school”), Safi Faye returned home to practice a rural and mythological, personal and political cinema. Thus the beautiful Letter From my Village and Fad’jal were born, one focused on chronicling the seasons of a Serer village’s land, the other dreaming around the mythical origins of this same village. An African, rural voice had arisen, a female voice, that spoke in the first person.

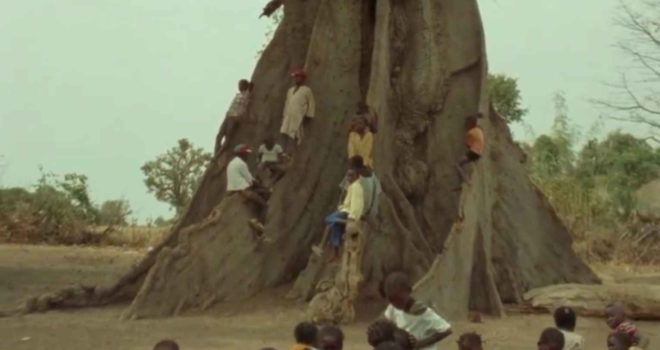

At the start of the 1980s the story of what would be her only fiction, Mossane, started to take root in Safi Faye’s imagination, but the film will only be born much later. As if she was waiting for it, the filmmaker shot commissioned works for big institutions like the UN or UNICEF, or international television programs; documentary films with a profuse, generous approach, always attentive to the described situations’ historical and political depth. Thus Souls in the Sun (1981) and Selbé, One Among Many (1982), which sings women’s bravery through precise tableaux of village life, without letting go of a specifically political content. This, from I, Your Mother (1980) whose documentary system subtly and even lightly spans the clichés of exile films. Thus the inspired Nourishing Embassies (1984) which draws a moving portrait of a century of exile, war and oppression from a somewhat folkloric pretext. Up until Mossane, the last film, in which Safi Faye invents a village tragedy about a young woman whose great beauty causes her death.

It is said that Safi Faye came from a line of Serer chiefs. We like to imagine her as a far-off descendant of Mbang Fad’jal, the mythical founder of the village of Fad’jal, seizing a camera to send us a missive beginning by the opening lines of Letter From my Village: “here is my village, my farmer parents, my big family…”.

Aisha Rahim

Letter by Anita Sankalé

Anita Sankalé is a member of Safi Faye’s family and her cousin. She lives in Nantes, and came to the Festival des 3 Continents to discover Safi Faye’s films, having only seen Mossane on DVD a few years ago. We invited her to join us for a screening of the same film on 28 November at the Cinématographe. She chose to read this text (presented here in French, the original version). We would like to thank her warmly for joining us for this retrospective.

Ma cousine Safi était plus âgée que moi, j’étais plus proche de sa sœur Soukeyna hélas décédée il y longtemps. Safi elle nous a quittés cette année, elle aurait eu 80 ans le 22 novembre juste avant l’ouverture du festival. Décès subit pour ses proches :

« Maman est partie » a dit Zeina sa fille, à ses tantes ? Partie où ont-elles répondu…

Safi je l’ai bien connue à Dakar, lorsqu’elle était institutrice.

Elle vibrait d’énergie. Je n’ai appris son cursus ultérieur en anthropologie qu’il y a quelques années. La discrétion et la modestie étaient sa marque.

Je savais qu’elle était devenue cinéaste, mais je n’ai vu Mossane qu’il y a quelques années lorsqu’elle m’a envoyé le DVD du film pour une diffusion en comité restreint à la Maison de l’Afrique à Nantes.

Film merveilleux, fiction, qui décrit les traditions en pays sérère et plus généralement au Sénégal, dans les villages restés attachés à leur culture forte, qui souvent contraint les femmes.

Féministe Safi, on le voit dans chacun de ses fims.

Ici le mariage arrangé, auquel habituellement cèdent les jeunes filles, auquel la jeune, belle et rebelle Mossane refuse de se plier;

Cette semaine j’ai vu Lettre paysanne, Fad’jal, et Moi, ta mère.

Dans les deux premiers : poésie d’un film lent qui évoque la lenteur du temps qui passe dans les villages, mais aussi la solidarité, l’âpreté de la vie, les ressorts qui poussent les jeunes à aller chercher du travail. Des documentaires dont on ne ressort pas indemne, qui m’ont profondément rappelé mes racines maternelles sérères.

Dans le troisième film, Moi, ta mère, quelle émotion de voir jouer la mère, la sœur et le père de Safi à différents moments, notamment lorsqu’à la toute fin du film tante Sokhna dicte une lettre à sa fille Yvonne pour son fils étudiant en Allemagne;

Yvonne porte le prénom de ma mère. Elle m’avait prévenue de cette scène. J’en suis sortie très émue et Yvonne, ses sœurs, ainsi que la fille de Safi, me remercient de les représenter à Nantes et surtout vous remercient vous, public, d’être présent nombreux pour découvrir l’œuvre de leur chère Safi Faye.

Anita Sankalé