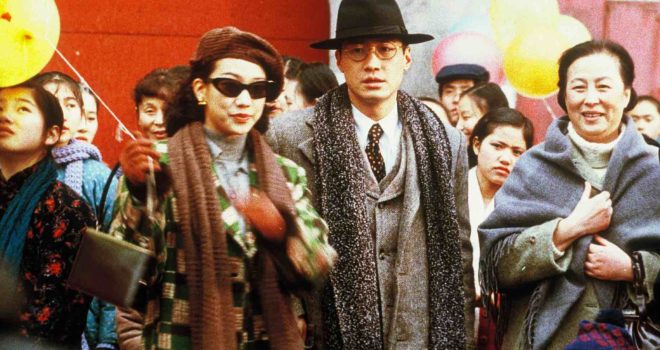

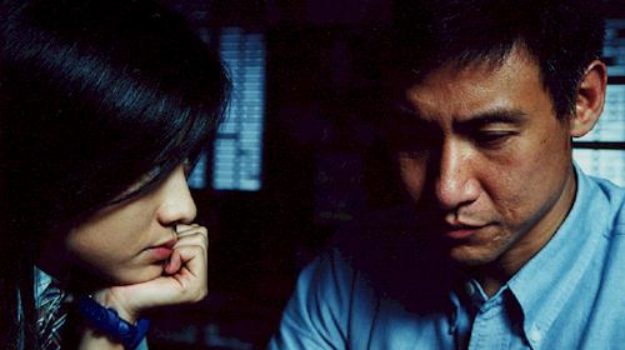

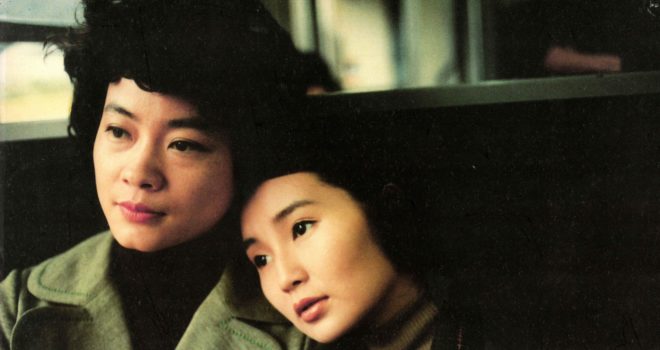

SONG OF THE EXILE by Ann Hui

With over 30 feature films to her credit since 1979, Ann Hui is the most prolific female director in the history of Asian cinema. But her status in the Hong Kong movie scene is paradoxical, to say the least. Despite not being as recognized by Western audiences as her male New Wave counterparts (Johnnie To, Wong Kar-Wai, John Woo, Patrick Tam, Tsui Hark, Yuen Woo-Ping), her films from the late 70s and early 80s count among those that signalled the rebirth of a form of cinematography that would become among the most emblematic in all of Asia. This retrospective is an invitation to explore a body of work that spans genres (thrillers, melodramas, swashbuckling epics…), and focuses closely over a long period on issues of exile, history, and Hong Kong Chinese identity.

(1) She doesn’t like to talk about her work

Odd it might seem, and disappointing it might be, to see Ann absenting herself from a retrospective of her work. But worry not: Whether in private, during interviews and on stage in front of an audience, she has the tendency to bat questions away with the much-practiced routine of a shrug, an awestruck expression, some infectious laughter, and finally a “I haven’t thought about that”.

Over the years, during many a conversation I’ve had with her during her publicity rounds for a new release, she has insisted she’s not interested to explain her motive and elaborate about her films’ raison d’être. She doesn’t say that because she considers all this yakking as beneath her; instead, more than once, she told me – in her trademark mix of modesty and irony – she’s just a “jobbing director”.

And her filmography seems to support her claim: counting political melodramas, supernatural comedies, action thrillers and literary biopics among her work, she seems not to have a distinct “style” as such, with hardly a central thematic plumb line underscoring the mammoth oeuvre which spans across six decades. It’s as if she’s just making them up as she goes along, doing whatever that comes her way.

But a hack she definitely isn’t. This is someone who studied English and comparative literature at the University of Hong Kong, and went on to study filmmaking in London for another two years. She knows cinema inside out and is a bona fide cinephile; her master’s thesis was about Alain Robbe-Grillet.

Maybe she doesn’t want people to confuse her biography with her creativity? Her lifelong fascination is the impact of dislocation on people – an issue very close to her, as someone who was born in northern China with a Japanese mother, raised in colonial-era Hong Kong, studied in Britain and worked (briefly) in Singapore, exile is commonplace in her work. It ranges from the Vietnamese migrants in Boat People and The Story of Woo Viet, the flight of anti-Qing revolutionaries in The Romance of Book and Sword/Princess Fragrance, a Chinese student entangled in Japanese mobster melees in Zodiac Killers, a woman’s comical defiance of her rural roots by reinventing herself as a savvy English teacher in Shanghai in The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, and the southward flight to Hong Kong of Chinese people of various stripes in Song of the Exile and The Golden Era.

(2) She doesn’t like to write

Just as much as Ann hates talking about her films, she doesn’t like to write that much either. She’s never penned a memoir; all the books about her – and there have been very few, admittedly – are about her, written by others.

In some ways, Ann is like Martin Scorsese or, closer to home, Johnnie To. She has something to say, but she’d rather have a writer to put all those ideas into a script – or, in some cases, to find an existent written text which fits her thinking. And she happens to have worked with some of the best screenwriters of her generation: Joyce Chan (The Secret, Spooky Bunch, Boat People), Wu Nien-jin (Song of the Exile), Ivy Ho (July Rhapsody), Li Qiang (The Golden Era) and Wang Anyi (Love After Love).

(3) She doesn’t work with the same people for a long time

Unlike many of her similarly seasoned peers, Ann doesn’t work out of a grand office with an army of assistants at her disposal; mostly, she works alone in the petite office of her company, Class Productions, in the downtown neighbourhood of Wan Chai. She doesn’t have a constant array of actors she works regularly with. Her forte lies with her dexterity in working with collaborators and transforming their ideas and performances into her own image.

And her collaborators are very good indeed. Apart from the splendid screenwriters (with whom she would work for a few years), her actresses are simply stellar. Hong Kong cinema stalwart Josephine Siao won a Best Actress award at the Berlinale with Summer Snow; Loretta Lee showed her real dramatic credentials with her Golden Horses win with Ordinary Heroes; and long-overlooked veterans Paw Hei-ching and Deanie Yip hitting late-career highs with The Way We Are and A Simple Life. The leads shine bright, brighter than the director sometimes.

(4) She doesn’t like to travel

When I first helped the festival to approach Ann about the possibility of her presence at Nantes, she was hesitant. Not that because she doesn’t feel honored, but she said her 76-year- old body couldn’t handle long-haul travel that well anymore. She did manage to get herself together to brave the odd transcontinental flight, such as when she went to pick up her Lifetime Achievement Award at the Venice Film Festival in 2020. She also said she’s always on the go: a planning of a project there, post-production of another elsewhere, and maybe some local promotion of a new release too. As you read this, she’s preoccupied with the domestic and Taiwanese roll-out of Elegies, a documentary about Hong Kong poets living far and wide across Asia.

But Ann was among the first of her New Wave generation whose work ventured overseas: Her second and third features, The Story of Woo Viet and Boat People, premiered at Cannes back in 1982 and 1983. But Ann never comes across as someone very enamoured about the spotlight. A couple of years back, after the release of The Golden Era, I asked Ann whether she’s going to take a break after the torturous, long-winding production of that film.

No, she shot back sharply: there’s so much she’d still like to do, and she’s not going to lose any time before it runs out altogether.

Chain smokers do hate flying, and that’s probably why Ann is reluctant to go on long trips. Sometimes I wonder whether Ann’s most comfortable place at a premiere of her film is actually outside the cinema, where she could take a drag, relax – or maybe even have a chat with similarly nicotine-needing audience members.

Maybe it’s partly because of all this – her hesitation to fly, to meet and greet, to be locked in a room talking about things she might have talked about multiple times before, or even to take care of films she made many many moons ago – that her work remains comparatively underappreciated abroad. So it’s a joy that her diverse filmography could be celebrated at the 3 Continents this year – a showcase of her state of mind, and also the change in the state of things in Hong Kong across the most tumultuous decades of its existence.

Clarence Tsui

Clarence Tsui is a Hong Kong-based journalist, film critic and festival programmer.